Level III Ducks Unlimited conservation priority area, supporting a large percentage of waterfowl that winter in Mexico

The mainland West Coast of Mexico contains several important areas for waterfowl. These habitats consist of tidal estuaries connected with brackish water marshes along the coast and inland fresh water wetlands and reservoirs. The wetlands of Mexico provide critical wintering habitat for waterbirds from across North America. Concern about the loss of waterfowl habitats south of the border led to the creation of Ducks Unlimited de Mexico (DUMAC) in 1974. The first organization of its kind established in Mexico, DUMAC pioneered efforts to conserve the nation's wetlands and wildlife, and, today, is the country's leading nongovernmental wetlands conservation organization.

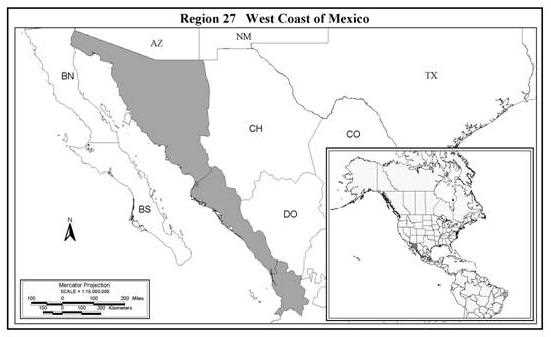

The mainland west coast of Mexico (Region 27*) contains several important areas for waterfowl. These habitats consist of tidal estuaries connected with brackish water marshes along the coast and inland fresh water wetlands and reservoirs. Fresh water streams and irrigation water empty into tidal lagoons and create flats, tidal pools, mangrove swamps and emergent vegetation dominated by cattail, bulrush, wigeongrass, muskgrass and algae.

The coastal and interior wetlands in the state of Sinaloa support 22.5% of the migratory waterfowl that winter in Mexico. The states of Sonora and Nayarit held 6.1% and 4.5%, respectively. These wetlands and their wildlife are currently threatened by intensive agriculture, pollution, and development by the shrimp industry along the 2,124 km of littoral habitat that exists in the three states. Sonora encompasses 1,200 km with 66,000 ha of wetlands; Sinaloa 656 km with 453,200 ha of wetlands, and; Nayarit has more than 268 km where Marismas Nacionales encompass 200,000 ha.

Adjacent to the west coast lies 1.2 million ha of irrigated agriculture in the state of Sinaloa (including Los Mochis, Guasave, Guamuchil and the Culiacan agricultural valleys) and approximately 456,000 ha in the state of Sonora (including the Yaqui and Mayo valleys). These upland areas were converted to intensive agriculture during the last 30 to 40 years. As a result there have been major changes to west coast wetlands, as they have become less saline, more densely covered by cattails, and subjected to discharges of agricultural pesticides and fertilizers.

During the last decade, the shrimp industry has grown rapidly and caused important changes in the wetland areas of the three states. In Sinaloa for example, 227 shrimp farms have modified 21,357 ha of intertidal and mangrove swamps. There is only limited regulatory control by the state and federal governments. An additional 200,000 ha are targeted for more of this development (Dir. Pesca, Gob. del Estado de Sinaloa 1999). Thus we are concerned that there will be further deterioration those wetlands. We have observed considerable habitat loss following the construction of 11,000 ha of shrimp farms in the Chiricahueto area and on Pabellon Bay. The shrimp farm industry has not grown as much in Sonora (5,252 ha) and Nayarit (1,217 ha) but the potential for this to happen is enormous (Carrera and de la Fuente 1995). The shrimp industry and agriculture are the most significant threats these areas will face in the near future. Growth of the shrimp industry is supported by a loan from the World Bank.

Much of the irrigated farmland supported rice production after it was developed. This crop is very beneficial to waterfowl. However, between 1981 and 1998, rice production has decreased in the state of Sinaloa from 65,900 to 2,400 ha. This was correlated with a drop in use of the region by northern pintail from 880,000 birds in 1989, to 228,000 in 1990 and 310,000 for 1991. About 5,000 ha of 21.2 million ha of agricultural land on the west coast is currently in rice production. These changes are due to production costs in comparison to other crops.

The complex of coastal wetlands along the states of Sonora, Sinaloa and Nayarit, represent the most important habitats for waterfowl in Mexico. Key wetlands in this area account for 33.1% of the total waterfowl population that winters in Mexico (USFWS 1989). On these wetlands during the 1980s, El Tobari Bay normally held, 1.8%, Lobos Bay, 0.3%, Santa Barbara, 1.6%. Agiabampo, 2.4%, Topolobampo Bay, 7.3%, Santa Maria Bay, 1.7%, Pabellon Bay, 9.4%, Caimanero, 1.9%, el Dorado to Dimas, 2.2% and Marismas Nacionales, 4.5% of the wintering waterfowl in Mexico (USFWS 1989). In January 1997, the USFWS reported a total of 627,787 ducks and 24,797 Geese, distributed along the western mainland. Of the ducks reported, 556,390 were dabblers and 71,397 were divers. Of the dabblers, the northern shoveler accounted for 251,950 (45%), the pintail, 151,740 (27%), blue-winged and cinnamon teal, 45,375 (8%), green-winged teal, 45,695 (8%) and American wigeon, 43,825. Of the divers, scaups accounted for 43,430 (64%), redhead, 17,900 (26%), ruddy duck 3,950 (6%) and canvasback, 2,050 (3%). Of the geese reported black brant accounted for, 22,720 (92%), snow geese 1,405 (6%) and white-fronted goose, 662 (3%).

*Region 27 - NABCI Bird Conservation Region 33 Sonoran and Mohave Deserts

The west Mexican wetlands and associated uplands support a diversity of wildlife species, particularly birds. The states of Sinaloa and Nayarit lie in the ecotone between two global climatic regions - the neotropic and the nearctic. Numerous mammals, including species of felids, still exist, such as the jaguar, ocelot and jaguarundi. The state of Sonora accounts for 894 species of wildlife, including 150 species of mammals, 474 species of birds, 131 species of reptiles, 37 species of amphibians and 102 species of fish (Moreno 1992). The states of Sinaloa and Nayarit, account for 482 species of wildlife (SEPESCA 1990), of which 51 are mammals, 347 are birds, 60 species are reptiles and 23 species are amphibians. Among these, 99 species are categorized as endemic and 73 species as in danger of extinction.

The coastal estuaries of Western Mexico are of global importance for wintering shorebirds of the Pacific Flyway. During 1993-94 ground surveys documented over 795,000 shorebirds wintering in the coastal bays of Pabellones and Santa Maria in Sinaloa. These surveys indicated that these areas support nearly one third of the shorebirds wintering in the North American portion of the Pacific Flyway (Engilis et al. 1998). These areas and the rest of the coastal wetlands of Sinaloa and the state of Sonora may well support over half of the shorebirds wintering on the Pacific Coast of North America. Two bays, Bahia Santa Maria and Ensenada Pabellones are sites of great importance to North American shorebirds in general. Both clearly exceed criteria of the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network for classification as International Sites, hosting >100,000 individuals. Further surveys may elevate these areas to sites of Hemispheric Importance, by hosting >500,000 shorebirds.

The future of agriculture in Mexico, particularly in the states of Sonora, Sinaloa and Nayarit is very uncertain but there may be opportunities for implementing programs that benefit wildlife. Many fields are no longer producing crops because of the lack of subsidies and the high cost of production. Many landowners would welcome it if national or international interests would lease their properties so they can avoid debt and secure some measure of profit. Also, in Mexico communal farms known as Ejidos are becoming the property of the occupants as a result of changes in the constitution. We believe there are opportunities to secure some of these lands for wildlife habitat that would be beneficial for migratory waterfowl and other birds.

DU must work in partnership with local and national conservation institutions, to support conservation efforts that protect the most important habitats for waterfowl along the states of Sinaloa, Sonora and Nayarit. An example exists in a current project with Conservation International, at Bahia Santa Maria, in Sinaloa. Since many areas are under either state of federal protection, conservation initiatives must be developed in cooperation with municipal, state and federal governments. DU must seek a more effective role in the development of the shrimp industry by working with the three levels of government in Mexico to provide information and assistance.

There has been very little research to support future conservation planning in this region. Basic wetland ecology information is needed. Specific studies are needed on the ecology of cattail (Typha) on specific sites in Santa Maria and Pabellones Bay. A monitoring program is needed for migratory and neotropical species using the wetlands. Finally, public awareness of wetland and waterfowl conservation needs are imperative to support future conservation and sustainable use of the resources of this region.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy