Level II Ducks Unlimited conservation priority area, breeding grounds for harlequin ducks, threatened by urban sprawl

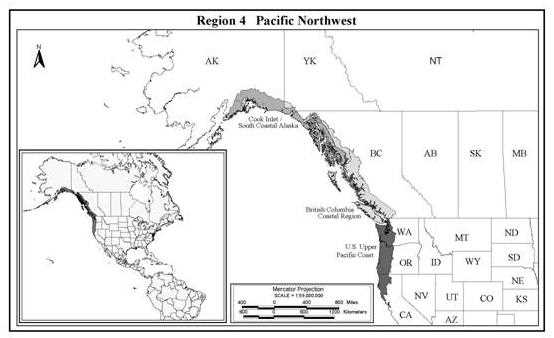

The Pacific Northwest region extends from Cook Inlet on the south coast of Alaska through coastal Alaska, British Columbia, Washington and Oregon to northern California. The important waterfowl habitats tend to be similar estuarine, riverine and forested wetland landforms throughout the region. However, the intensity of land use and future threats to waterfowl conservation are extremely different between, for example, the wilderness of Alaska and the urbanized Fraser River delta. Strategic plans for this region have been prepared in three sections: Alaska, British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest of the United States.

Alaska | California | Oregon | Washington

British Columbia

The Pacific Northwest region (Region 4*) extends from Cook Inlet on the south coast of Alaska through coastal Alaska, British Columbia (BC), Washington and Oregon to northern California. The important waterfowl habitats tend to be similar estuarine, riverine and forested wetland landforms throughout. However, the intensity of land use and future threats to waterfowl conservation are extremely different between, for example, the wilderness of Alaska and the urbanized Fraser River Delta. Strategic plans for this region have been prepared in three sections: Alaska, British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest of the U.S.

Cook Inlet (28,000 km2) composed of the lower Matanuska-Susitna River valley into the Inlet and the coastal southeast panhandle of Alaska (61,000 km2) make up the 1,600 km arc of these regions. Both regions are characterized by high annual precipitation in a maritime climate. One-half of Alaska's human population lives in the Cook Inlet-Anchorage bowl, with an additional 15% of the population living in the Southeast. The regions are heavily forested, with black, white, and sitka spruce and western hemlock as the climax needleleaf communities. Broadleaf forests are found along floodplain river and riparian drainages. More than half of the wetlands are forested or bog communities. Lakes in the upland areas cover some 10% of the terrain. Scrub and bog wetlands and wet forb and sedge vegetation dominate open areas. Thousands of small coastal wetland marshes occur along the shoreline and large wetland expanses exist at the Susitna Flats, Copper and Stikine Deltas, and the Yakutat forelands. Periodic tectonic uplift has altered the sub-tidal mudflats to marsh and mixed forests. Glaciation has been the major force in creating present-day landforms in the Copper and Stikine basins. The Copper River basin is the sixth largest basin in Alaska with an area of 62,000 km2. These regions include more than 40,000 km of tidal shoreline.

These regions provide nesting and molting habitat for the world's population of dusky Canada and tule white-fronted geese, most Vancouver Canada geese, more than 40% of all trumpeter swans, and substantial numbers of mallards, mergansers, and other ducks. Large rafts of sea ducks (scoters, mergansers, harlequin ducks) and mallards and Vancouver Canada geese winter in bays or estuaries of the regions. Over 10 million waterfowl and 10 million shorebirds utilize the Yakutat, Stikine, Tsiu, Copper and Susitna Flats in spring migration. The breeding area of the tule white-fronted goose was destroyed by the volcanic eruption of Mt. Redoubt. Dusky Canada goose habitat was modified by an earthquake in 1964 that shifted the hydrology and plant succession within the Copper River Delta.

Large tracts of these regions are in public ownership. The two largest National Forests (NF) in the U.S. are found here in the Tongass (6,883,000 ha) and the Chugach (5,263,160 ha) NF, which includes the 283,400 ha Copper River Delta. Other protected areas include Kenai NWR, Glacier Bay and Kenai Fjord NPs, and BLM's forelands of the Bering Glacier. Alaska Department of Fish and Game is responsible for large tracts of land in the southeast, including Susitna Flats, Palmer Hay Flats, Potter's Marsh, and Tsiu Flats.

Some 80% of the people of Alaska live within the coastal arc of Anchorage to Ketchikan. Industry in the region consists of oil and gas production, commercial fishing, logging, mining, and minor agriculture. The only extensive threat to waterfowl would come from contamination of the estuarine habitat. There have been waterfowl kills from the grounding of the Exxon Valdez, oil pollution in Cook Inlet, and pulp mill effluent in Sitka and Ketchikan. By 1986, over 133,600 ha had been logged on the Tongass NF. This resulted in some 5,600 km of roads, of which 2,703 km impacted wetlands, for a direct degradation of 810 ha (USFWS). Protection and riparian restoration in existing harvested areas is critical in the Copper, Susitna, Tsiu, and Stikine Deltas. The Exxon Valdez spill in Prince William Sound demonstrated the impact of one serious marine accident. If coastal storms or tides bring the toxins into the estuaries, a major portion of our continent's waterbirds could be threatened.

*Region 4 - NABCI Bird Conservation Region 4 ( Alaska only – Region 4 for Yukon and SE Alaska is covered in Western Boreal Forest, Bird Conservation Region 6.)

In 1998, the Kenai-Susitna USFWS strata averaged 11.5 ducks/km2, whereas, the Copper Delta USFWS strata averaged 32.5 ducks/mi2. These systems have traditionally been used as spring staging areas. Cook Inlet and the Copper River Delta are among the most important wetlands to the world's populations of western sandpiper and dunlin. The Stikine is also a traditional fall staging area for Wrangel Island snow geese. Common wintering shorebirds include black oystercatchers, rock sandpipers, black turnstones, and surfbirds. Seabirds (murres, murrelets, auklets) are common breeders throughout Prince William Sound. Southeastern Alaska has over 2,800 important anadromous fish streams, and over 15,000 bald eagles use this habitat.

Initial efforts in Southeast Alaska have concentrated on education and landscape planning. Partnerships with the USFS (USFS), BLM, USFWS, Alaska Science Center, and Alaska Department of Fish and Game have resulted in remote sensing products for the Copper River Delta, Kenai Peninsula, and Bering Glacier forelands. Fieldwork has been completed for GIS work at Susitna Flats. Extensive conservation planning has occurred through the development of the Copper River Delta GIS product. Current efforts include modeling of vegetation successional changes, which will have significant impact on dusky Canada goose, trumpeter swan, and northern pintail use of the Delta. More recently, efforts have been initiated to restore and enhance wetland habitats that have been dramatically altered by construction of towns, roads, railroads and other developments. Significant wetland enhancement opportunities exist in Southeast Alaska, primarily altered estuarine habitats in close proximity to coastal communities.

Important waterfowl habitats in the Upper Pacific Coast region in the U.S. include estuaries, riverine wetlands, marine habitats, floodplain marshes, wet prairies and isolated potholes of coastal Washington, Oregon, and northwest California. Critically important wetland complexes in this region include Samish Bay, Skagit River Delta, Snohomish River estuary, Puget Sound, Hood Canal, Grays Harbor, Chehalis River floodplain, Willapa Bay, Columbia River estuary, Willamette Valley, Tillamook Bay, Coos Bay/South Slough, Coquille Valley, Klamath and Eel Rivers, and Humboldt Bay.

The Pacific Northwest is a high rainfall zone with annual precipitation exceeding 250 cm in some locations. The diverse topography in the region, combined with high precipitation, has resulted in a rich and diverse mix of wetland habitats within this ecosystem.

Major rivers in the region have carved out extensive freshwater floodplain habitats and created large estuarine systems, both of which are used by hundreds of thousands of waterfowl. Prior to settlement by Europeans, some areas in the region contained extensive freshwater wetland habitats, including a huge complex of wet prairie wetlands in the Willamette Valley.

Pacific coast wetlands have been degraded by human expansion. Large-scale timber harvest and development of agricultural lands have resulted in direct wetland loss, sedimentation of bays and degradation of water quality and submergent plant beds. Extensive urbanization and industrialization has eliminated entire wetlands and reduced the value of other coastal wetlands to waterbirds. Many of the estuaries along the Pacific coast have been diked and drained, primarily for agricultural development. For example, approximately 95% of the Skagit River estuary has been drained. Expanding urbanization eliminates connections among wetlands, disrupts natural hydrologic flow patterns, and results in few areas that are without human disturbance.

Marine, estuarine and freshwater habitats along the Pacific Coast are complex. Migratory waterfowl, particularly puddle ducks, depend on tidal estuaries, freshwater floodplain marshes, riverine habitats, isolated freshwater wetlands and flooded agricultural lands in this region. Diving ducks primarily forage in riverine, estuarine and coastal marine wetlands. The coastal zone is a critical migration and wintering area for sea ducks. Aquatic beds of eelgrass are present in many of the region's bays and are heavily used by Pacific brant, wigeon, diving ducks, and many other waterbirds (alcids, loons, cormorants, and grebes). Many of these beds have been destroyed or reduced because of shellfish mariculture, wetland drainage and water quality problems.

The Upper Pacific Coast of the Lower 48 of the U.S. is divided into six subregions: Puget Sound, Washington Coast, Lower Columbia River, Oregon Coast, Willamette Valley, and Upper California Coast.

Puget Sound and the Strait of Georgia stretch 290 km south from the Canadian border to Olympia, WA. Tidal variations provide expansive intertidal habitats for shorebirds and waterfowl. Large bays and estuaries characterize the northern Puget Sound. The principal rivers (Nooksack, Samish, Skagit, Stillaguamish, Nisqually and Snohomish) formed extensive floodplains that support palustrine marshes, riparian corridors, and expansive agricultural zones. Principal crops grown in the region include barley, cold leaf crops, carrots, potatoes, and hay. Fallow fields are utilized heavily by staging and wintering waterfowl. In the northern Puget Sound, eelgrass beds are extensive in Skagit, Padilla, and Samish Bays, while Port Susan, Bellingham and Lummi Bays support tidal marshes with less eelgrass. The "upper intertidal zone" in all of these areas has been largely lost due to diking and draining activities, primarily to convert these areas to agricultural fields. The middle reach of Puget Sound is heavily altered. The Seattle-Tacoma Metropolitan area has a population approaching 8 million people. The Puget Sound has one of the highest population growth rates in the country. The Hood Canal and Nisqually River Valley are the primary wetland habitats in the southern Puget Sound.

State protected wildlife areas include Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife lands at Skagit, Lake Terrell, Nisqually, Sequim, and Snoqualmie. Federally protected lands include Nisqually River Estuary, Dungeness Spit, and Padilla Bay. The northern bays of Puget Sound support nearly 80% of western Washington's wintering waterfowl. The loss of freshwater and estuarine wetland habitat in the region has shifted waterfowl habitat dependency to agricultural lands in the past 100 years, particularly in the Skagit Delta. Mallard, wigeon, and northern pintail make up nearly 90% of the total puddle ducks wintering in the region. The heaviest concentrations occur in Port Susan, Skagit, and Padilla bays. Marine habitats in the Puget Sound, along with similar habitats in coastal Washington, account for 46% of the goldeneyes and 49% of the buffleheads wintering in the Pacific Flyway. Urbanization, with its associated loss of wetlands and agricultural lands, degradation of existing wetlands, and lowered water quality, will be the greatest threat to these waterfowl populations.

The Skagit River Delta and Samish Bay support over 30,000 Wrangel Island snow geese and hundreds of thousands of ducks during the migration and wintering periods. Waterfowl counts exceeding one million birds have become increasingly common in the Skagit and Samish bays. Padilla Bay winters over 10,000 Pacific brant, the largest wintering population of this species north of Mexico (Ball et al. 1989). The Skagit Delta is also an important region for more than 700 wintering trumpeter swans. These swans, along with 1,500 tundra swans, forage in grain fields, fallow potato fields, and tidal estuaries. The Olympic Mountains and rough coastal areas of the Outer Sound support the densest U.S. breeding population of harlequin ducks. Hydroelectric dams, deforestation, and development have threatened this Mergini species through much of its nesting range in the Cascade and Sierra Nevada Mountains. The Hood Canal supports numerous Barrow's and common goldeneye, in addition to wintering white-winged and surf scoters.

Washington's Pacific Coast (not including Puget Sound) is a sloping beachfront cut by Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay. Willapa Bay constitutes one of the largest and most pristine estuaries in the U.S. Its shallow contours make it unusable as a deep-water port and the Bay supports the state's largest commercial shellfish beds. A threat to this habitat is the introduction of smooth cordgrass. This invasive weed is choking out important mudflats and aquatic beds. Efforts are underway to assist the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife to control smooth cordgrass in Willapa Bay and other coastal habitats. Grays Harbor is fed by several lentic systems including the Chehalis River, which has a large expanse of bottomland habitats.

Waterfowl utilize Washington's coastal bays primarily during migration. American wigeon compose some 80% of these migrants, which may reach 50,000 birds per fall. Some 90,000 scoters are counted annually during midwinter surveys with over half occurring in western Washington (Ball et al. 1989). Large numbers of pintails migrate through these habitats. Canada geese are most numerous along Willapa Bay with a resident population of about 1,000 birds. Willapa Bay also holds between 800-1,500 Pacific brant in winter, with larger numbers staging in spring.

The Lower Columbia River area includes both the Oregon and Washington shores of the river from Bonneville Dam to the mouth. The Columbia River Estuary encompasses over 40,000 ha. Although there are no dams on the Columbia River below Bonneville, the system has been dramatically altered through dredging, ditching, and construction of flood control levees. In addition, an extensive dam system on the lower tributaries to the Columbia River have dramatically altered natural hydrology, affecting the natural processes that form and maintain wetland habitats. The heavily developed Portland-Vancouver Metropolitan Area has degraded the river system by extensive levee construction and drainage of floodplain wetlands. Much of the flat alluvial plains of the Columbia are currently managed as pastures, with some areas planted to annual and perennial crops. Recently, the conversion of many of these areas to cottonwood tree farms has degraded prime waterfowl foraging areas. The extensive loss and conversion of floodplain habitats in the lower Columbia River has not only affected waterfowl habitat, but is one of the leading factors in the decline of other species, including 12 stocks of salmonids listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Important wetlands managed by public entities in the region include: Ridgefield, Steigerwald, Pierce and Julia Butler Hanson National Wildlife Refuges managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Shillapoo, Vancouver and Chinook River Wildlife Areas managed by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; Oregon's Sauvie Island and Burlington Bottoms Wildlife Areas; Smith and Bybee Lakes, and Multnomah Channel habitats managed by Metro (the regional government entity for the metropolitan area of Portland); and the Sandy River Delta and other Columbia River gorge habitats managed by the U.S. Forest Service. The Columbia Land Trust, a local non-profit conservation organization, has developed a significant land protection program and has secured extensive wetland habitats in the lower Columbia River, especially in the Grays River estuary near the mouth of the Columbia River.

Over 150,000 ducks and geese use Sauvie Island and nearby wetland areas during peak migration. Over 250 avian species have been recorded there. Mallard, northern shoveler, American wigeon, northern pintail, and green-winged teal are the principle dabbling ducks, whereas, canvasback, ring-necked duck, and scaup are the principle diving ducks. Scaup and ring-necked ducks occur primarily in the Columbia River estuary. Aleutian and cackling Canada geese are migrants that pass through this region, and some 76,000 Canada geese winter in the Lower Columbia and Willamette Valley (Jarvis and Cornely 1988). Significant numbers of dusky Canada geese winter in this region. The Lower Columbia also supports the majority of the 8,000 tundra swans wintering in the Pacific Northwest (Ball et al. 1989). Wetland restoration projects in the region have also resulted in significant increases in numbers of locally breeding waterfowl, an important component of the local waterfowl harvest, particularly early in the season.

The Oregon Coast is characterized by a rugged coastline that is dissected by large rivers originating from the Cascade Mountains and coastal range. These rivers have created significant floodplain and estuarine wetlands. Along the coast, sand dunes trap freshwater and create coastal lakes, ponds, and palustrine marshes. Important river systems include Nestucca, Siletz, Yaquina, Alsea, Siuslaw, Umpqua, Coos, Coquille, Rouge, and New. In addition to providing important waterfowl habitat, Oregon's estuaries provide critical rearing habitats for anadromous fish. Losses of 50-80% of intertidal marsh habitat in Oregon's estuaries have resulted from diking for farmland conversion (Thomas 1983). Several small refuges, including Siletz Bay and Bandon Marsh NWRs, protect critical tidal wetlands, but no large public wetland complex exists.

The Coquille Valley supports the highest concentration of puddle ducks (dominated by mallard, pintail, wigeon, and green-winged teal) wintering along Oregon's coast. During harsh winters in the Great Basin, coastal Oregon experiences a 100-200% increase in bird use. Scoters are common wintering birds off several estuaries. Nestucca Bay supports the only coastal wintering population of dusky Canada geese (500 birds). Netarts, Yaquina, and Tillamook Bays all support wintering brant in small numbers. Aleutian Canada geese (over 10,000 birds) stage on pastures along the New River and Nestucca Bay.

This interior valley is approximately 49 km long and about 60 km at its widest point. It was created by one of the major tributaries of the Columbia, the Willamette River. Prior to settlement, this valley contained extensive systems of floodplain and wet prairie wetland habitats. It is believed that between 120,000 and 160,000 ha of wetland prairie existed in 1850. Today, less than 400 ha remain (Guard 1995). Public refuges exist at Slough, Ankeny, and Finley NWRs and Fern Ridge and E.E. Wilson WAs. The greatest threats to waterfowl habitat are expanding urban sprawl, intensive agriculture and degradation of existing wetland habitats.

The Willamette Valley winters large number of ducks, including more than 50,000 mallard and 30,000 American wigeon. Green-winged teal, pintail, and ring-necked duck are common migrants and wintering birds. Five different races of Canada geese winter in the valley, including virtually the entire population of dusky Canada geese and recently, most of the population of cackling Canada geese. Total numbers of wintering Canada geese have grown from 20,000 to over 250,000 birds in the last two decades.

From the border of Oregon, important waterfowl habitats in northwestern California include the 18,225 ha Smith River floodplain, the coastal lagoons of Lake Earl and Lake Talawa; deltas of the Klamath, Redwood, and Little Rivers, and the estuarine complex of Humboldt Bay, Mad River Estuary, and the Eel River Delta. This latter wetland complex is second only to San Francisco Bay in size or importance for waterfowl in coastal California. It provides at least 8,000 ha of low-lying seasonal wetland, 8,000 ha of tidal marsh or mudflat, and 1,800 ha of sloughs and deep-water estuarine habitats, plus 400 ha of rare floodplain riparian forest. Expanding human populations is the greatest threat, and urbanization results in direct loss of habitat and also greater disturbance of birds, nonpoint pollution, modification of hydrologic regimes, and diversion of water.

Significant wetland conservation efforts in this region have been completed in the past five years. Additional wetland conservation projects are currently underway or planned for the future. Wetland conservation activities in the Lower Columbia Ecosystem have centered around four NAWCA grants. Two NAWCA grants in Willapa Bay and five grants in the Puget Sound have provided significant partnerships and financial resources for wetland conservation activities. The U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service has become a significant partner in wetland conservation activities in the region through the Wetland Reserve Program. Salmon recovery efforts have brought millions of dollars to the region to restore and protect important wetlands and riparian areas. Ducks Unlimited has capitalized on these efforts by securing millions of dollars from the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board and the Salmon Recovery Funding Board of Washington. Most of the wetland conservation projects completed by DU in this region provide significant benefits to salmon, particularly by providing rearing habitat to juvenile coho and Chinook salmon.

As extensive wetland restoration projects are completed in the Lower Columbia River and additional opportunities become less common, focus is shifting to other areas, primarily the Puget Sound region. Opportunities for restoration of floodplain and estuarine wetlands in the Puget Sound are significant, primarily in the Snohomish River watershed. A major estuary restoration project will also be completed at Nisqually NWR. Additional projects are being pursued in all of these regions. One of the most significant issues facing ongoing management of floodplain freshwater habitats is reed canarygrass. This species is very competitive and routinely becomes the dominant plant species in freshwater, seasonal wetlands. Reed canarygrass provides little value to waterfowl or other wildlife. If left unchecked, freshwater wetlands can become virtually worthless to waterfowl as reed canarygrass eliminates other plant species. The installation of appropriate water management facilities and on-going, intensive management of seasonal wetlands is essential to maintaining diverse, productive wetland habitats that provide the nutritional requirements of wintering and migrating waterfowl.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy