Diving into the new research

Note: The information on this webpage is a supplement to the November/December DU Magazine "Ducks on the Move" article.

Table of Contents

Hunters are noticing changes in the skies—fewer ducks at familiar spots, migrations starting later, and birds lingering farther north. But are these shifts real, or just seasonal quirks? A recent study set out to find answers, using 60 years of band recoveries to track the fall and winter distributions of mallards, northern pintails, and blue-winged teal across the Central and Mississippi Flyways. Thanks to over 350,000 band recovery reports from dedicated hunters, researchers uncovered clear trends in how fall and winter duck distributions have changed between the 1960s and 2010s.

While previous research explored similar questions, this study examined whether changes in distributions varied among different subpopulations of ducks. These subpopulations were based on where the ducks were originally banded:

Researchers used an analytical tool called a “kernel density estimator” to identify areas where 50% (core distribution) and 95% (overall distribution) of band recoveries were most concentrated for each subpopulation. These areas were mapped separately for October, November, December, and January to determine if the changes in distribution were more significant in certain months.

Multiple metrics were used to describe the distributions of recoveries, but the maps below present two of the most important: the centroid of recoveries (a measure of average recovery location) and the area of the core and overall distributions of recoveries for each duck subpopulation.

Map Key:

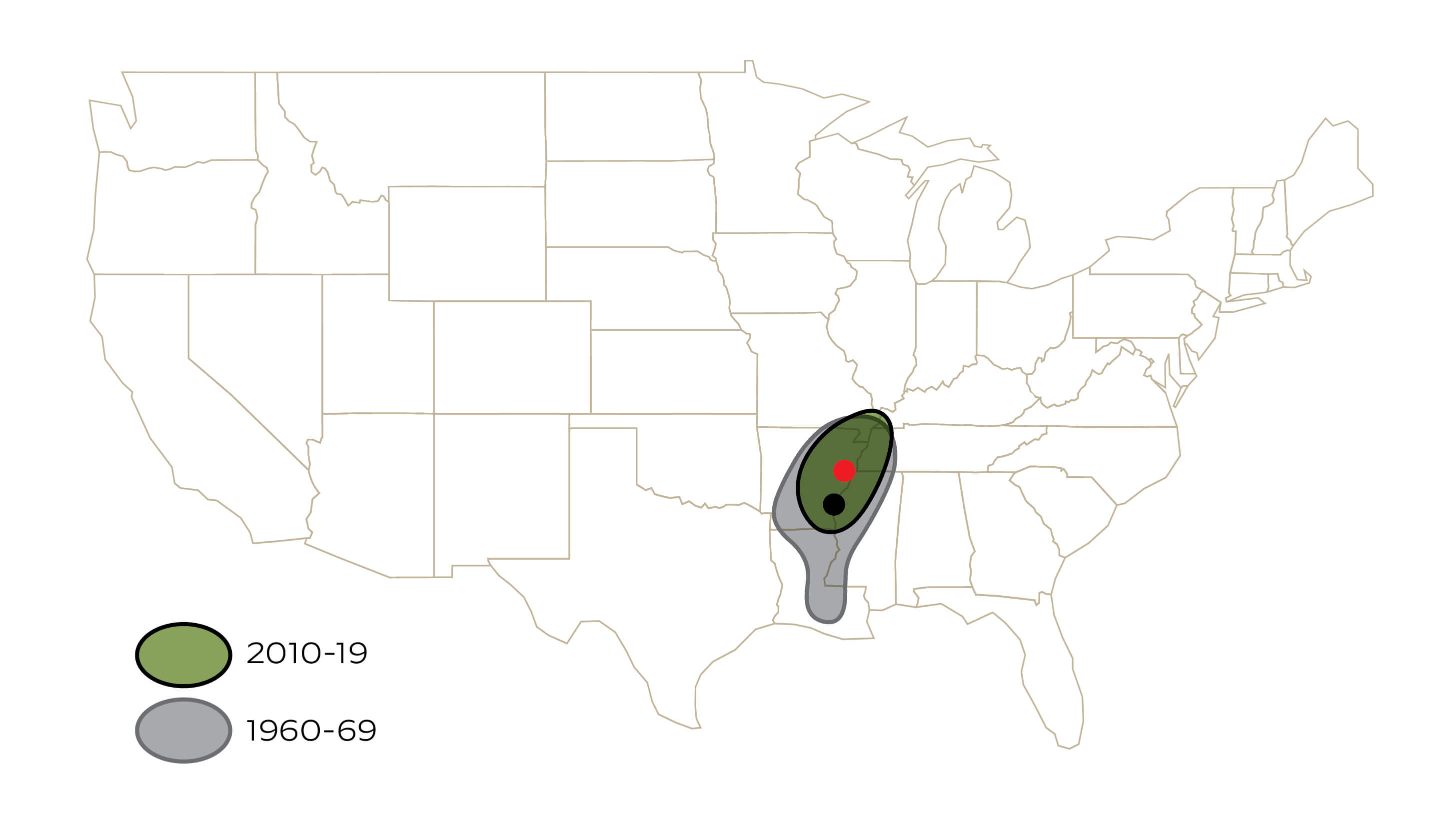

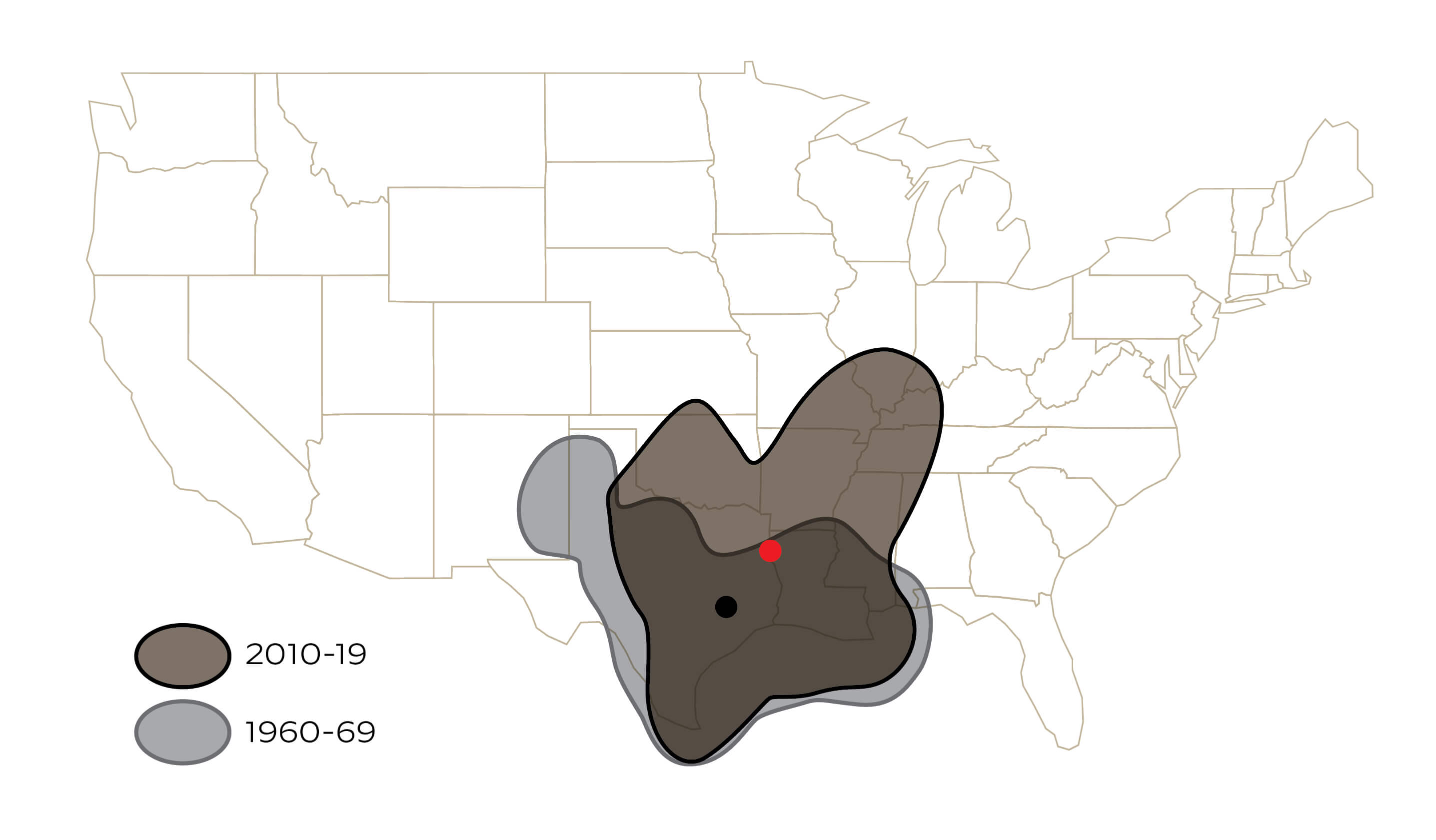

Canadian Prairie and Western Boreal Subpopulation, January Recoveries

The core distribution of January recoveries became more concentrated from the 1960s to 2010s but remained in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. In contrast, the overall distribution expanded to the northwest, reflecting an increase in mallard recoveries in the south-central Great Plains. The centroid of recoveries for the core distribution shifted northward slightly, while the centroid for the overall distribution shifted to the northwest.

The core distribution of January recoveries became more concentrated from the 1960s to 2010s but remained in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. In contrast, the overall distribution expanded to the northwest, reflecting an increase in mallard recoveries in the south-central Great Plains. The centroid of recoveries for the core distribution shifted northward slightly, while the centroid for the overall distribution shifted to the northwest.

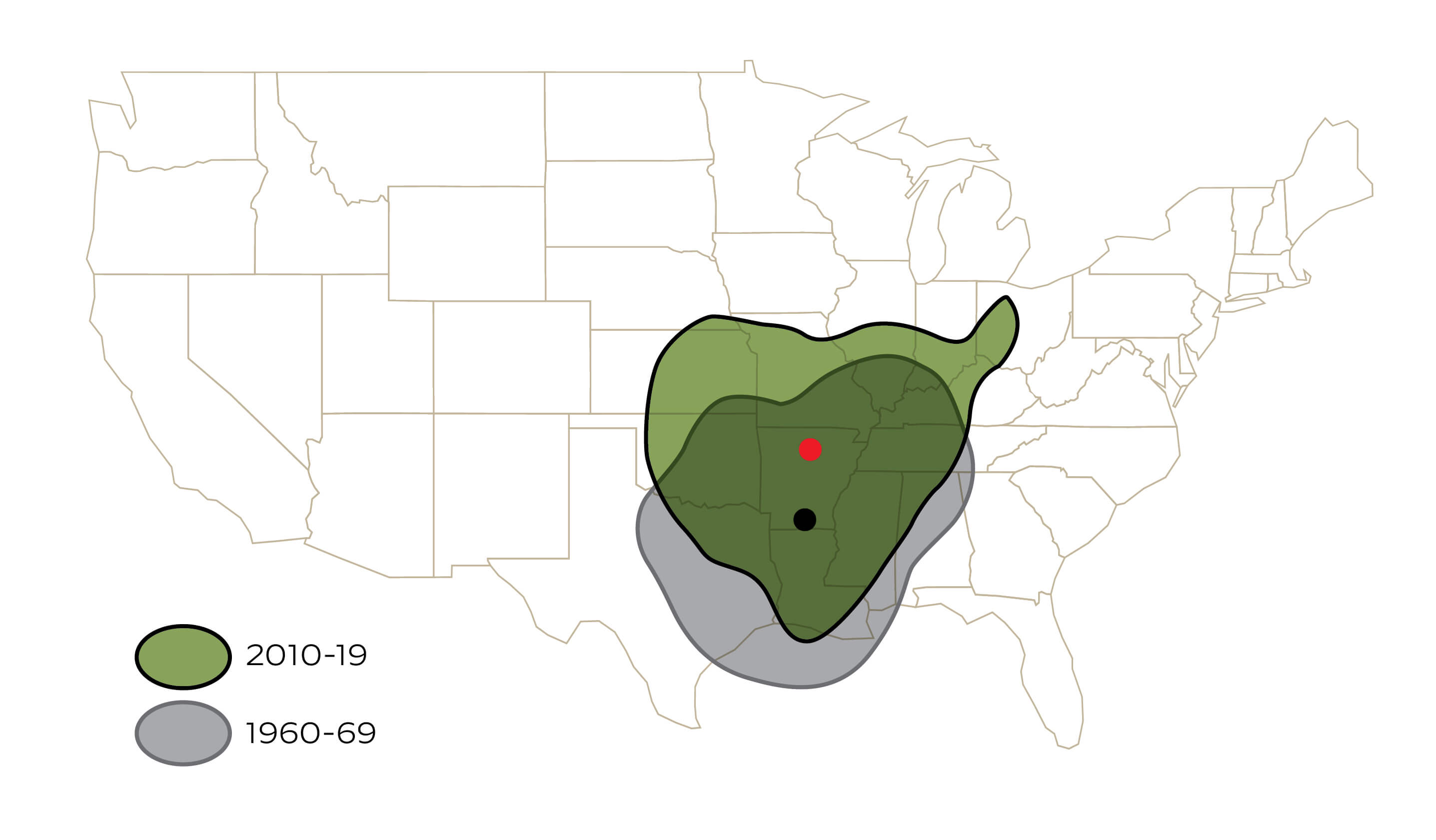

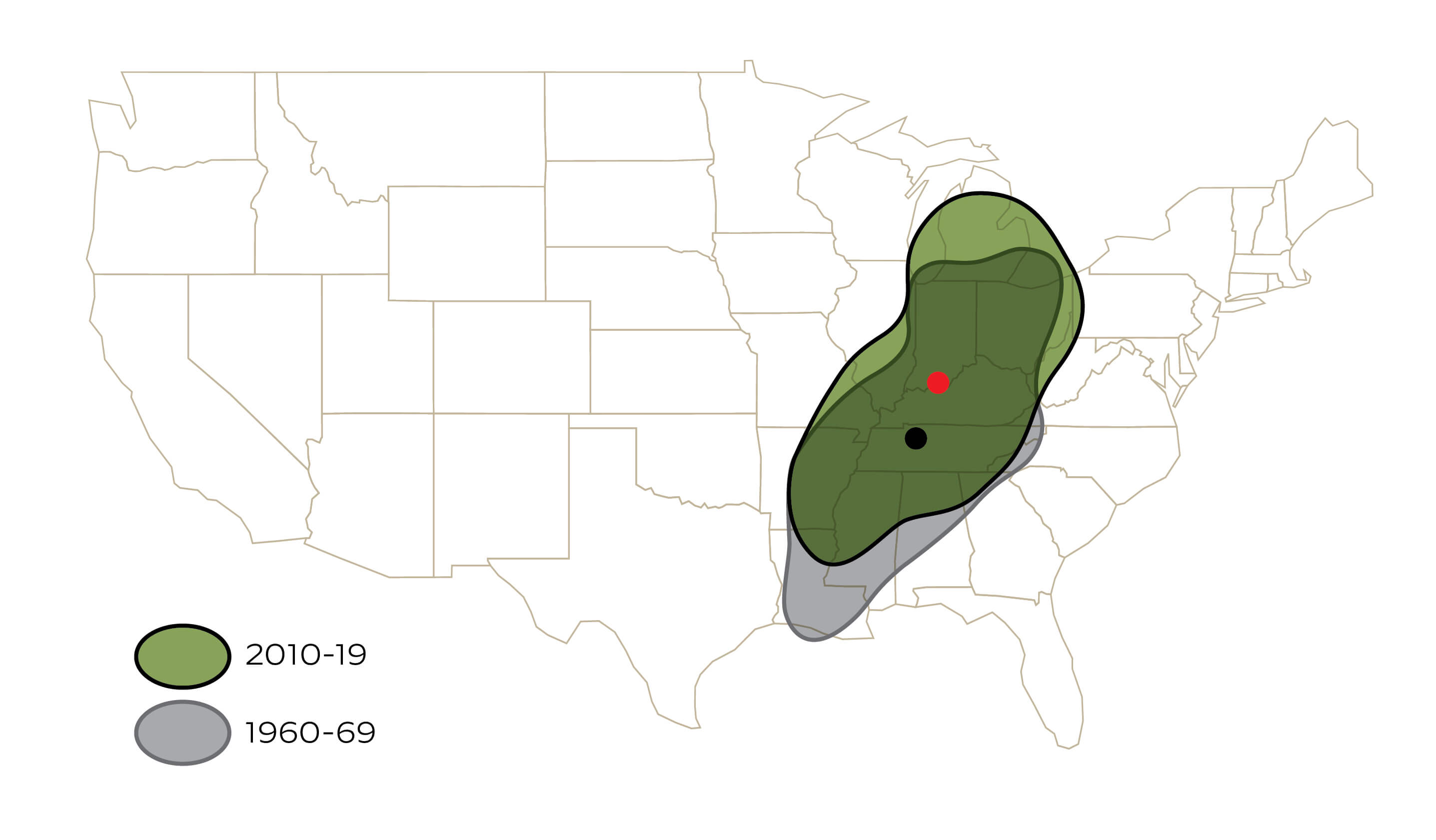

U.S. Prairie Subpopulation, January Recoveries

The area and centroid of the core distribution of January recoveries for mallards banded in the U.S. Prairies changed little between the 1960s and 2010s. However, the area and centroid for the overall recovery distribution shifted north, with notable contractions in the southern end of the recovery range.

The area and centroid of the core distribution of January recoveries for mallards banded in the U.S. Prairies changed little between the 1960s and 2010s. However, the area and centroid for the overall recovery distribution shifted north, with notable contractions in the southern end of the recovery range.

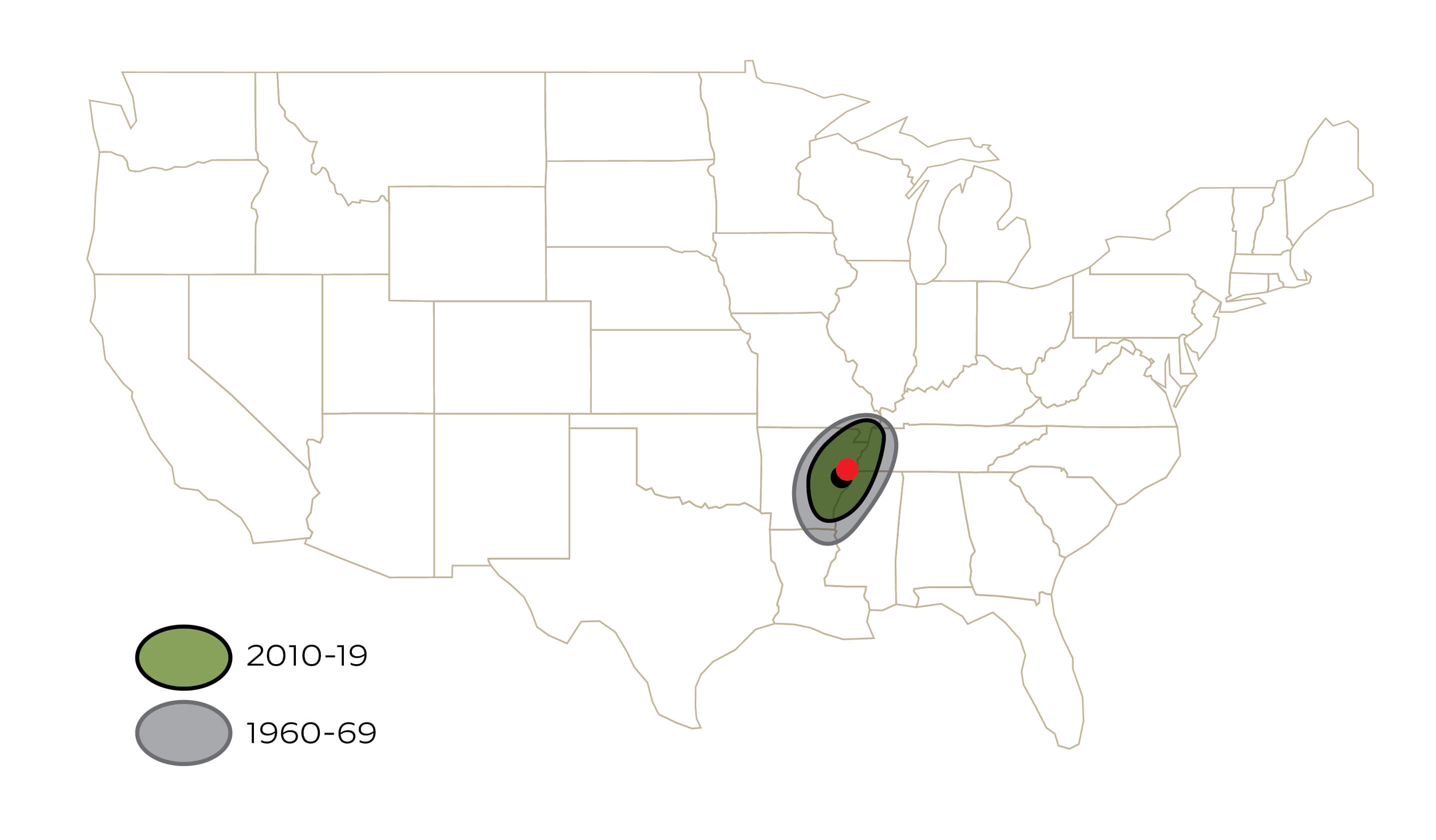

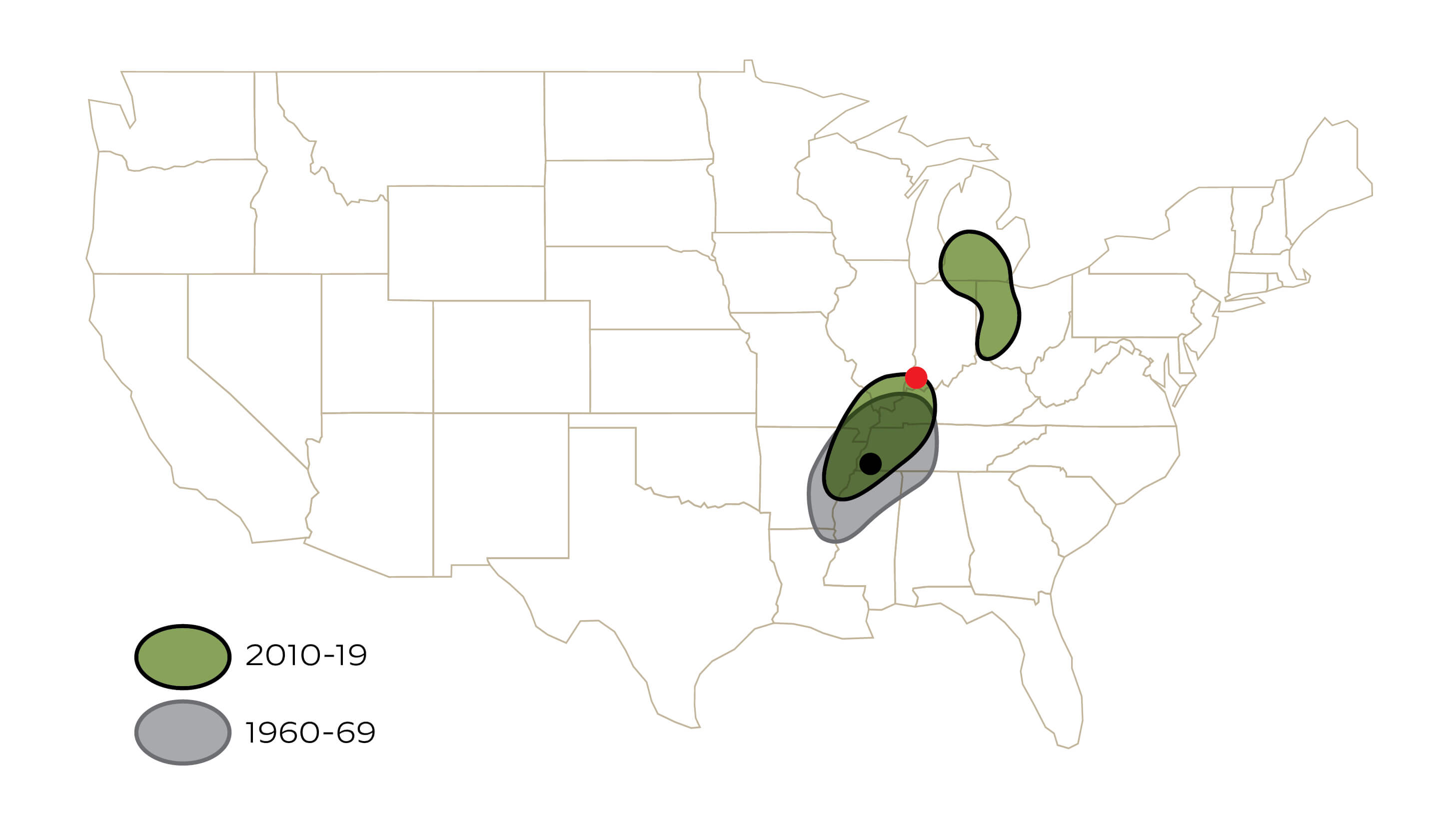

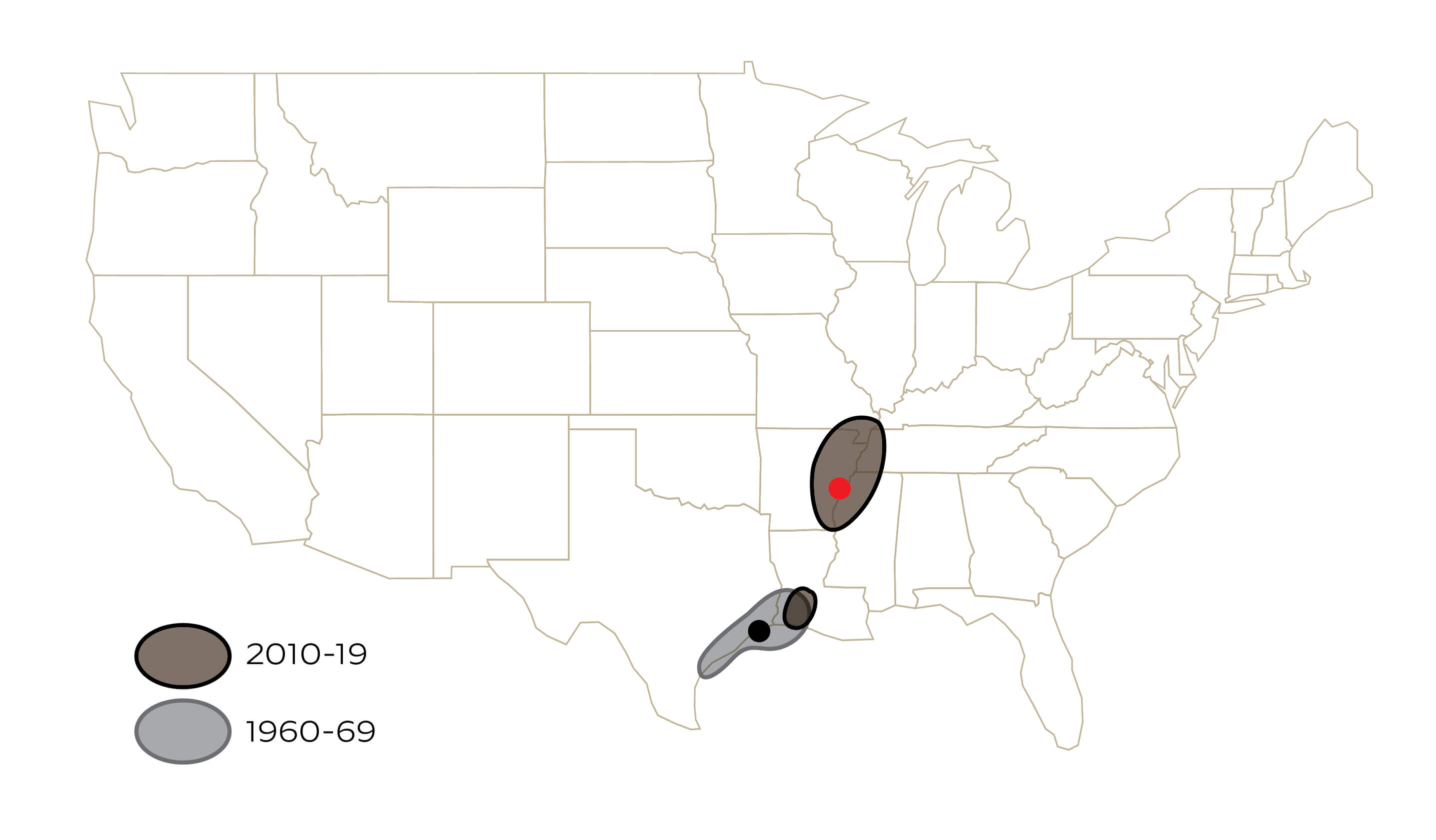

Great Lakes and Ontario Subpopulation, January Recoveries

Notable shifts to the northeast occurred for all metrics associated with January recoveries of mallards banded in the Great Lakes region and Ontario. The core distribution during the 1960s was centered in the lower Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys but shifted northeast by the 2010s, with a significant number of recoveries occurring in the Great Lakes region. Similarly, the centroid and area of the overall distribution shifted northeastward, such that few mallards from this subpopulation are now recovered at the southern end of the Mississippi Flyway.

Notable shifts to the northeast occurred for all metrics associated with January recoveries of mallards banded in the Great Lakes region and Ontario. The core distribution during the 1960s was centered in the lower Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys but shifted northeast by the 2010s, with a significant number of recoveries occurring in the Great Lakes region. Similarly, the centroid and area of the overall distribution shifted northeastward, such that few mallards from this subpopulation are now recovered at the southern end of the Mississippi Flyway.

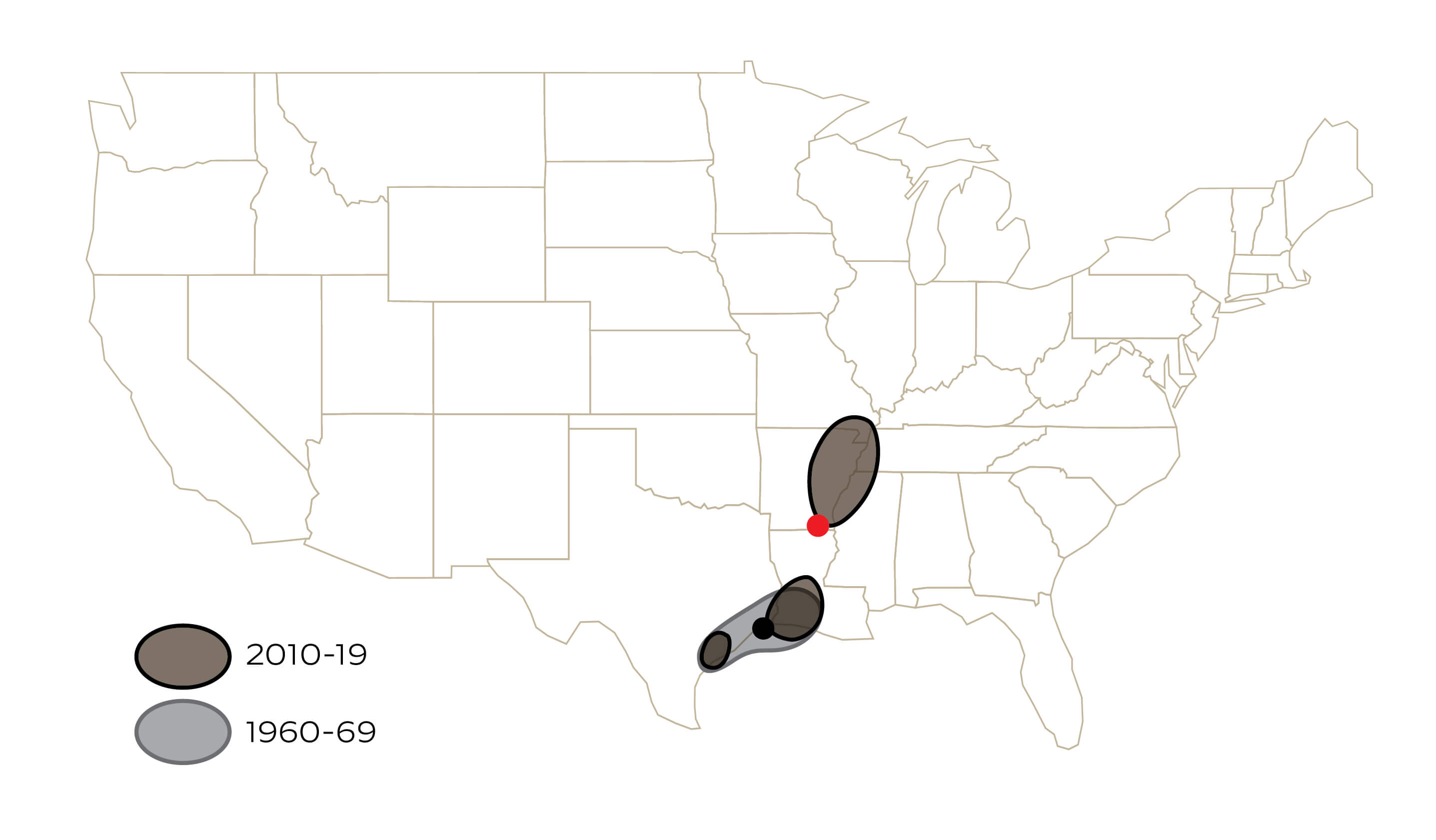

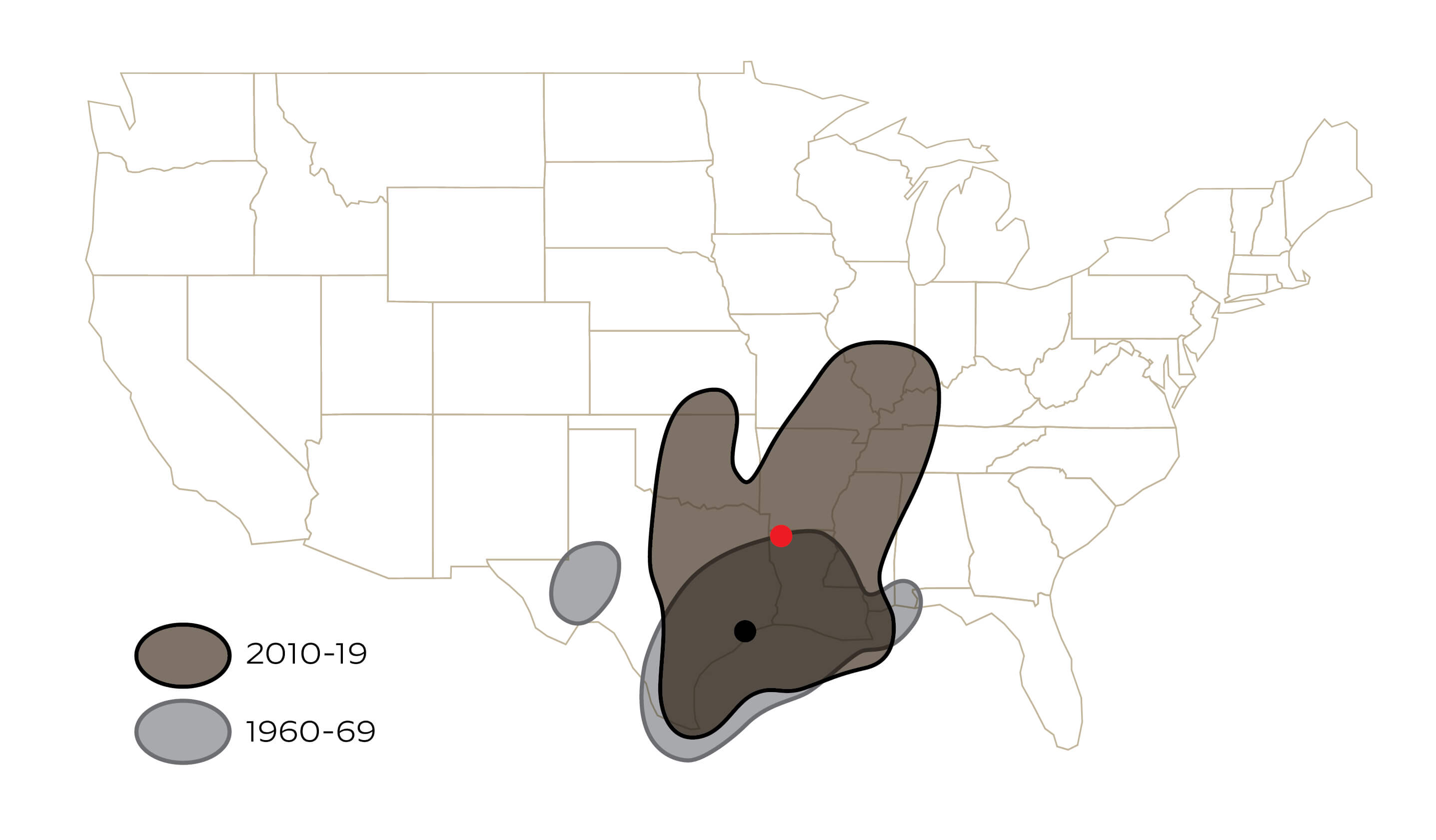

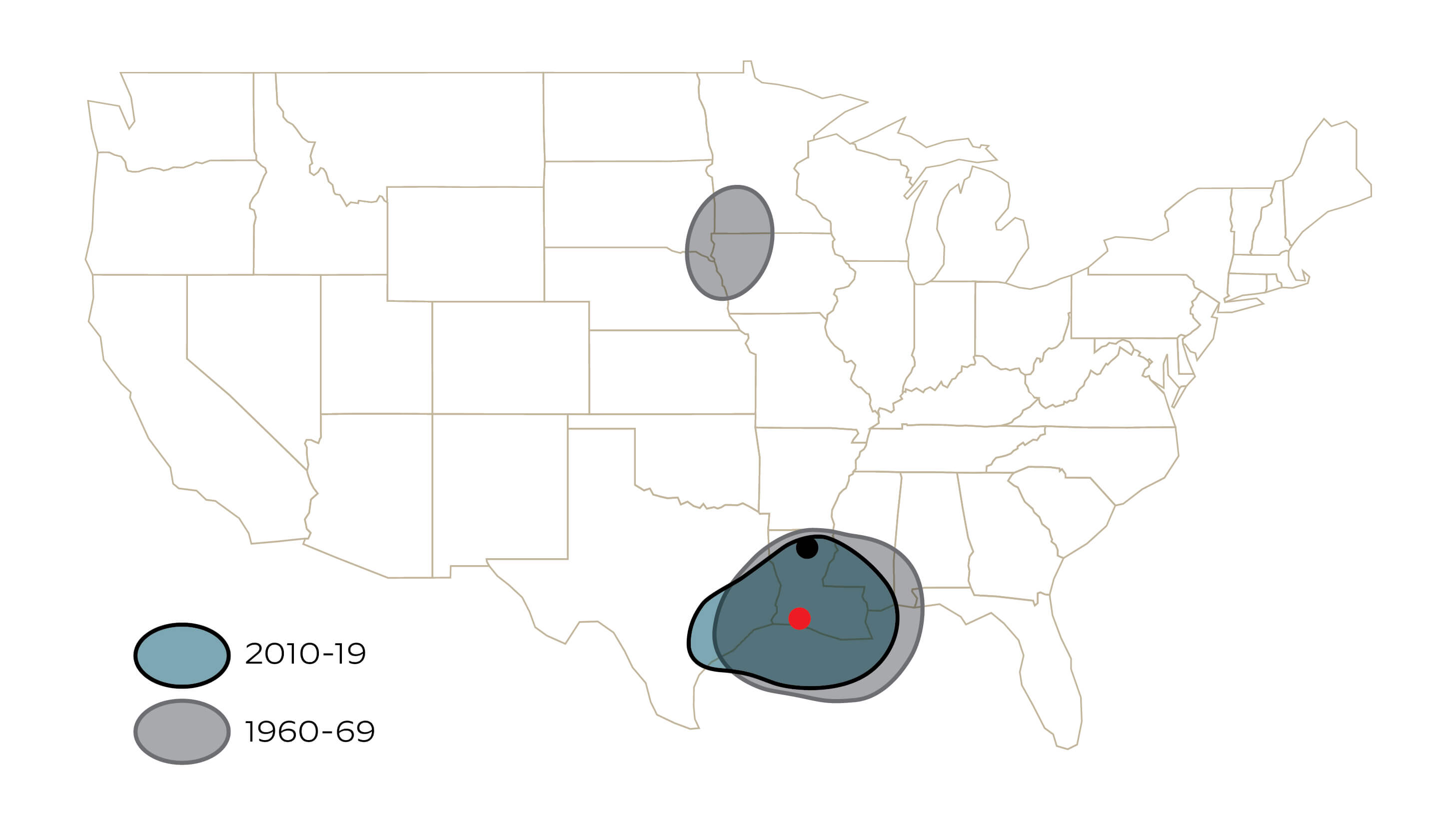

Canadian Prairie and Western Boreal Subpopulation, January Recoveries

The core and overall distributions for northern pintails banded in the Canadian Prairies and Boreal Forest demonstrated substantial shifts northward. The historical core distribution was the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana, but by the 2010s a significant number of recoveries were occurring in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. The overall distribution shifted northward but also expanded in area, with the Gulf Coast remaining an area of significant harvest for pintails.

The core and overall distributions for northern pintails banded in the Canadian Prairies and Boreal Forest demonstrated substantial shifts northward. The historical core distribution was the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana, but by the 2010s a significant number of recoveries were occurring in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. The overall distribution shifted northward but also expanded in area, with the Gulf Coast remaining an area of significant harvest for pintails.

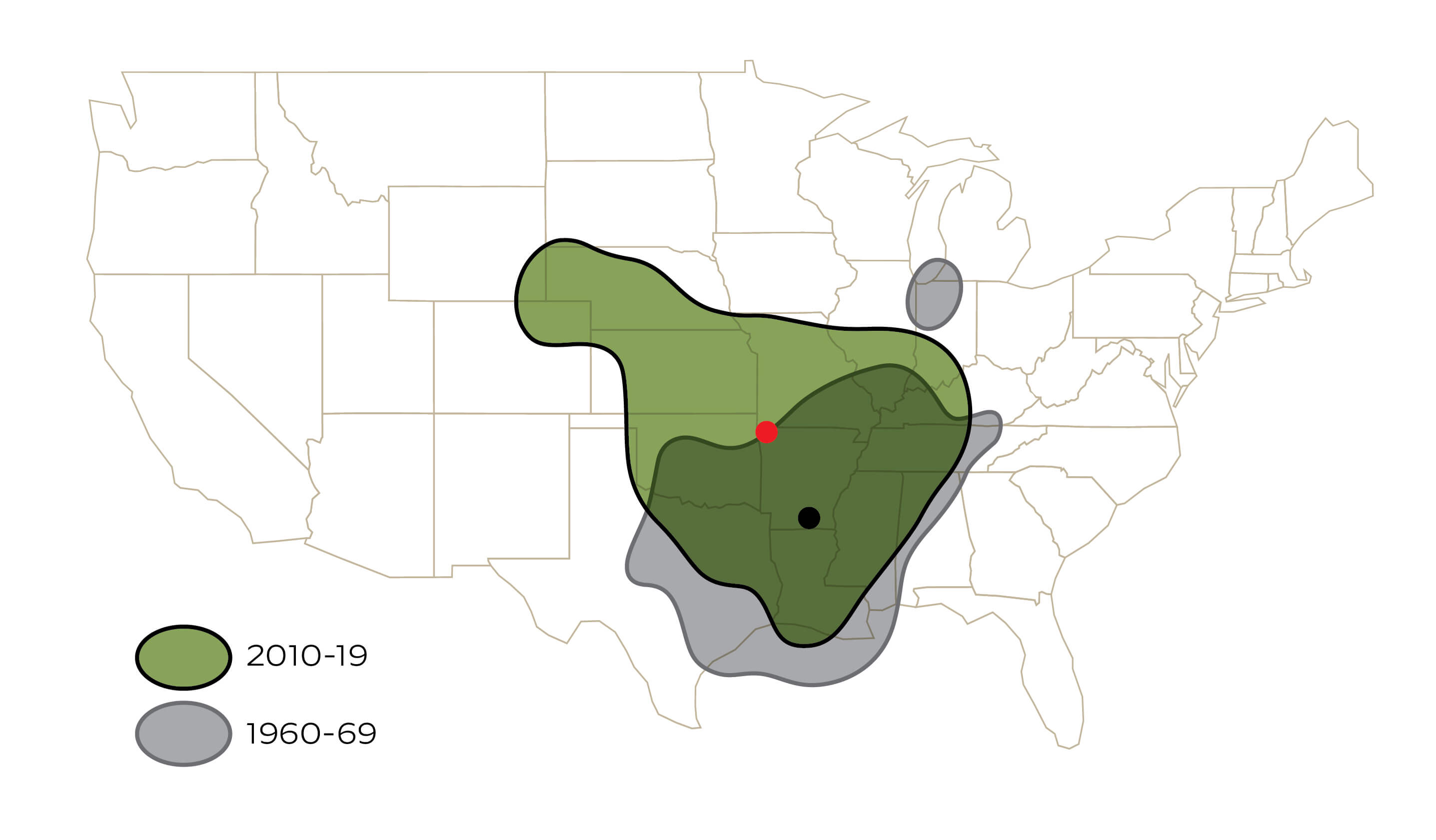

U.S. Prairie Subpopulation, January Recoveries

The change in recovery distribution for northern pintails banded in the U.S. Prairies was similar to the Canadian subpopulation but with a more prominent northward shift of the core distribution. The overall distribution also shifted northward and expanded in area showing that the U.S. Gulf Coast remains an important area for pintail winter distribution.

The change in recovery distribution for northern pintails banded in the U.S. Prairies was similar to the Canadian subpopulation but with a more prominent northward shift of the core distribution. The overall distribution also shifted northward and expanded in area showing that the U.S. Gulf Coast remains an important area for pintail winter distribution.

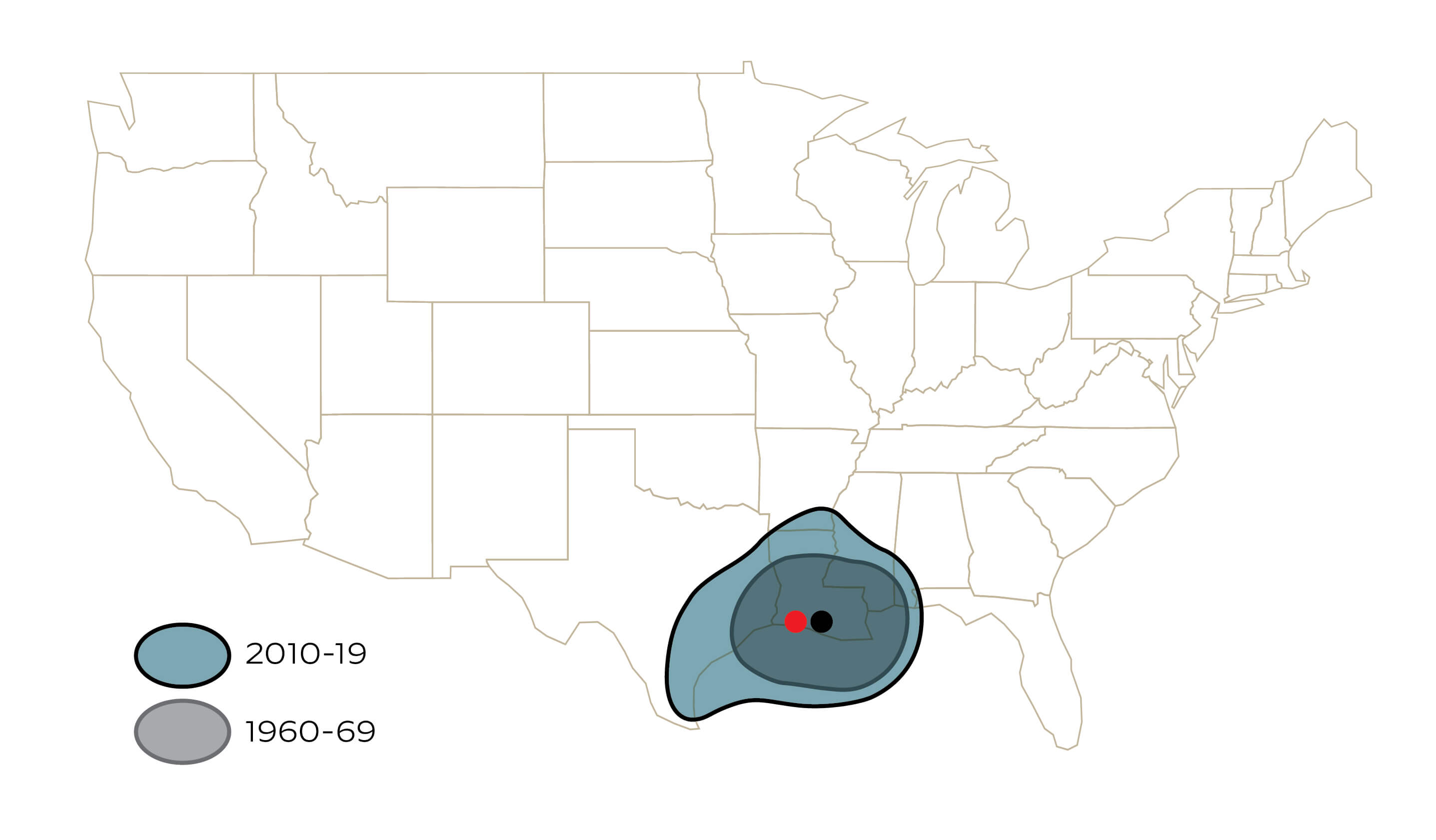

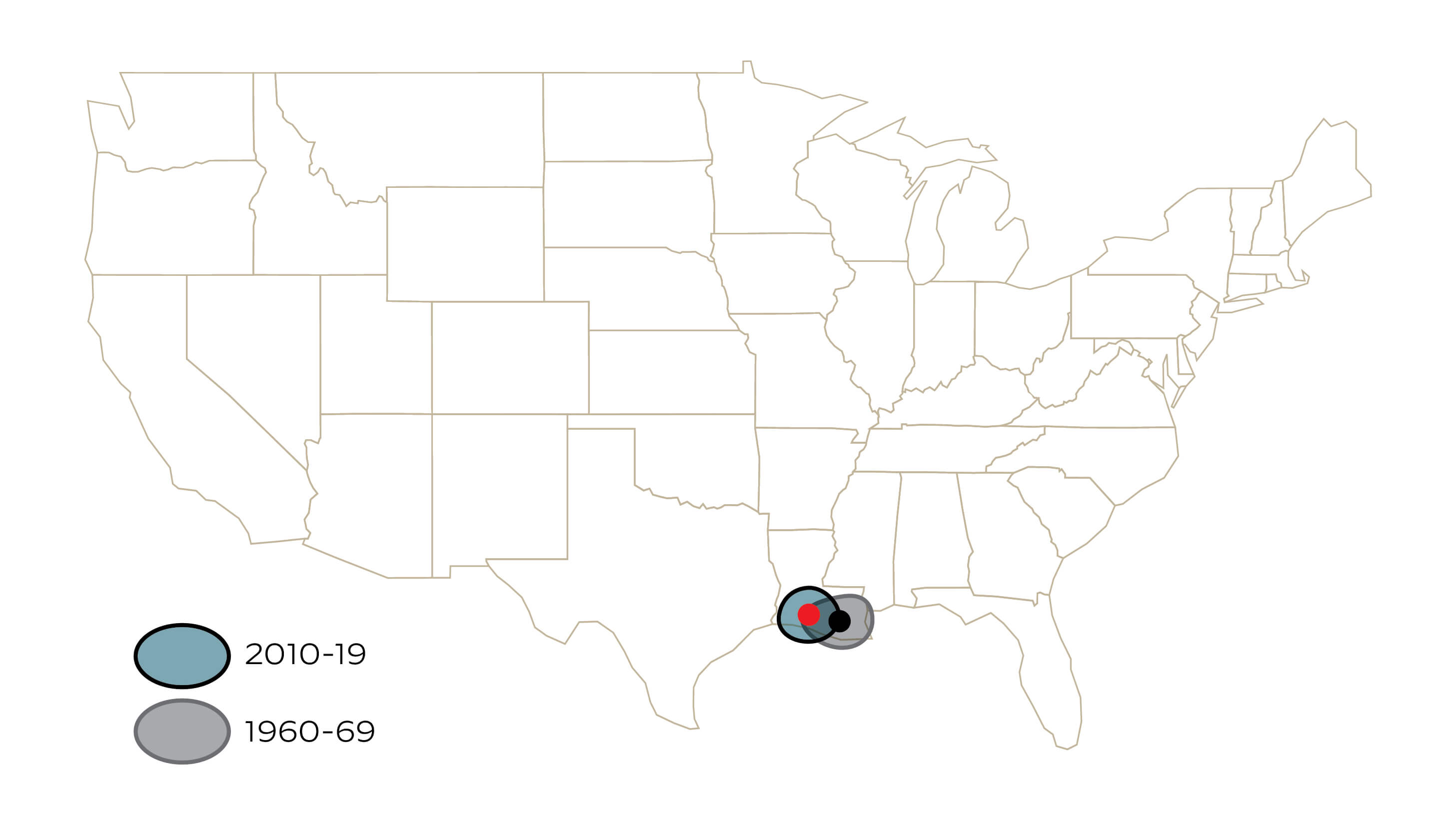

Canadian Prairie and Western Boreal Subpopulation, December Recoveries

The core distribution of blue-winged teal recoveries in December remains coastal Louisiana but with a notable shift into the marshes of southwestern Louisiana. The overall distribution has expanded such that an increasing percentage of blue-winged teal recoveries are now occurring in coastal Texas and the southern reaches of the Mississippi Alluvial Valley.

The core distribution of blue-winged teal recoveries in December remains coastal Louisiana but with a notable shift into the marshes of southwestern Louisiana. The overall distribution has expanded such that an increasing percentage of blue-winged teal recoveries are now occurring in coastal Texas and the southern reaches of the Mississippi Alluvial Valley.

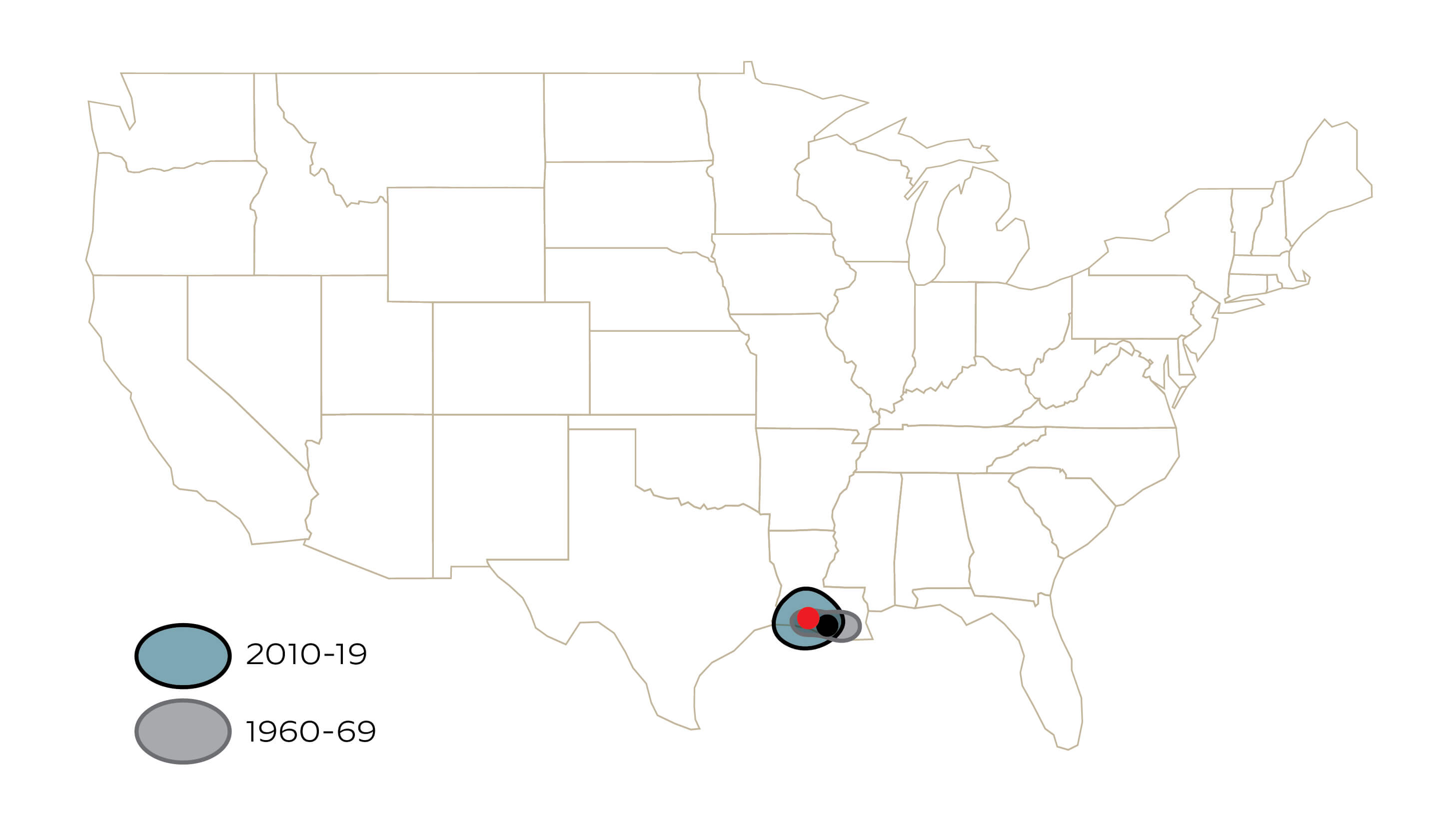

U.S. Prairie Subpopulation, December Recoveries

Shifts in December recoveries of blue-winged teal banded in the U.S. Prairies were similar to those for the Canadian Prairie subpopulation. The core distribution has shifted slightly west but remains centered on the coastal marshes of south Louisiana. The overall distribution of blue-winged teal recoveries remains at the southern end of the Mississippi and Central Flyways, with a slight expansion westward.

Shifts in December recoveries of blue-winged teal banded in the U.S. Prairies were similar to those for the Canadian Prairie subpopulation. The core distribution has shifted slightly west but remains centered on the coastal marshes of south Louisiana. The overall distribution of blue-winged teal recoveries remains at the southern end of the Mississippi and Central Flyways, with a slight expansion westward.

Scientists note that migration is a behavior that allows birds to cope with seasonal changes in resource availability. When landscapes and environmental conditions change across longer time frames, we should expect migratory behaviors to produce similarly persistent shifts in species ranges and seasonal distributions.

There is little argument about whether this is happening. Instead, research is now focusing on the factors underlying these changes and asking whether they can be addressed through management, conservation, or land-use activities. The next phase of this study is attempting to answer these questions, helping us understand bird responses to changing conditions and how future conservation efforts can address the needs of ducks and hunters across dynamic landscapes.

Learn More: Understanding Waterfowl Ducks on the Move

Study Citations:

Acknowledgements: This study was conducted by Dr. Bram Verheijen, postdoctoral researcher, and Dr. Lisa Webb, assistant unit leader, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Missouri Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit; Dr. Heath Hagy, project lead for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Habitat and Population Evaluation Team; and Dr. Mike Brasher, senior waterfowl scientist, Ducks Unlimited, Inc. Funding was provided by USGS Midwest Climate Adaptation Center, Mississippi Flyway Council, and Ducks Unlimited, Inc. A special thanks is extended to all waterfowl banders and supporting agencies in the U.S. and Canada, the USGS Bird Banding Lab, and thousands of waterfowl hunters who enabled this study by participating in annual waterfowl banding operations and reporting of recovered bands.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy