By Chris Madson

For some people, a commitment to conservation comes with maturity. Others have it bred into their bones. Scot Storm, winner of this year's Federal Duck Stamp Art Contest, grew up on the edge of the Chippewa National Forest in northern Minnesota and can't really remember a time when conservation wasn't part of his life.

"My dad always had Ducks Unlimited magazines around the house," Storm recalls, "and I remember looking through them and seeing the pictures and sketches and reading some of the stories. You start getting an appreciation of what you can do to make wildlife habitat better."

When he began attending DU banquets, Storm was struck with "how everybody had the same thoughts. You go to an event for different reasons, but the ultimate thing is we want to have wetlands, we want to have wildlife, and we want our kids and our grandkids to be able to experience some of the things we've seen," he says.

LAYNE KENNEDY

Scot Storm won the 2018 Federal Duck Stamp Art Contest with this painting of a wood duck and antique decoy. The painting recalls his early hunting experiences growing up in Minnesota.

USFWS

One look at Storm's artwork is enough to understand how the images of the wildlife and wild places he's seen have been etched into his mind. Not just the creatures, but the habitat, the moments, and the light. And in this year's federal duck stamp design, he had the chance to evoke another theme that has been crucial to the well-being of North America's waterfowl—hunting. According to the official rules of the contest, all entries for the 2019−2020 stamp were required to include "a visual element that features hunting."

"I thought that was such a neat idea," Storm says. He looked over his reference photos and decided to feature a pair of American green-winged teal in the painting with a hunter setting decoys in the background. He spent several weeks on the painting, but as he looked at it in his studio one afternoon, he decided "it just wasn't clicking the way I wanted." So with only a week left before the deadline, he says, he went back to another idea: "a simple wood duck and an old Mason decoy, which I kind of grew up with."

He had about five days to finish the composition. "I painted every moment I was awake," Storm recalls. "If you ask my wife, she would say she doesn't want to go through that week again because, at the end of it, I was getting pretty crabby."

This is one of only a handful of times in the history of the federal duck stamp that the winning artwork has alluded to hunting, the best known probably being Maynard Reece's famous 1959 portrait of the black Lab King Buck—two-time winner of the National Retriever Championship—with a mallard drake in his mouth.

In the 85-year history of the federal stamp, it has featured the work of just 66 artists. Only 13 have won the competition more than once. Storm is a member of that elite group. His work graced the 2004−2005 stamp and will appear again in 2019−2020. With those paintings, he joins a tradition that reaches back to one of the most influential artists and conservationists in American history—J.N. "Ding" Darling.

JIM THOMPSON

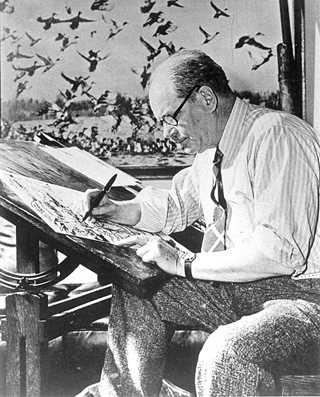

Much of the habitat conserved by duck stamp dollars is open to public hunting, wildlife viewing, and other outdoor recreation.

COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA LIBRARIES DING DARLING COLLECTION

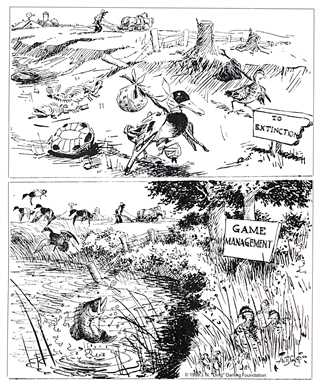

In a legendary misunderstanding, one of Ding Darling's preliminary sketches was used to create the first duck stamp, which went on sale in 1934.

USFWS

Nearly a century separates Storm from Darling, but the lives and careers of the two men bear some similarities. Like Storm, Darling was born in the north country—specifically, the logging settlement of Norwood, Michigan, at the mouth of Grand Traverse Bay about 40 miles southwest of the Straits of Mackinac.

In 1886, when he was 10, his family moved to Sioux City, Iowa, which in those years was still on the edge of the American frontier. He started hunting and fishing almost as soon as he could walk. He prowled the bluffs and backwaters along the Missouri River near his home and eventually widened his forays into the still-pristine prairies of eastern Nebraska and South Dakota.

The concept of wise use was just beginning to emerge in the upper Midwest of Darling's adolescence. Market gunning and spring waterfowling were still legal, and the flights of ducks and geese across the pothole country seemed inexhaustible. Darling wrote about his childhood with fondness: "Those were the days when the Golden Plover came in great flocks and moved across South Dakota, and, from early spring until the Prairie Chicken sought cover in the fall along the thickets bordering the creeks and marshes, my mind was filled with pictures which have never been erased." The subsequent degradation of many of Darling's childhood haunts inspired his passion for conservation: "If I could put together all the virgin landscapes which I knew in my youth and show what has happened to them in one generation, it would be the best object lesson in conservation that could be printed."

Like Storm, Darling was largely a self-taught artist, sketching people and scenery as a youngster over the moral objections of his father, a Protestant minister, and his devout mother. His caricatures of professors and staff got him expelled from Beloit College for a year, and after his delayed graduation, he continued his development as a satirist and cartoonist at the Sioux City Journal. In 1906, he moved to Des Moines to become the editorial cartoonist for the Des Moines Register and Leader, a position he held for most of the rest of his life.

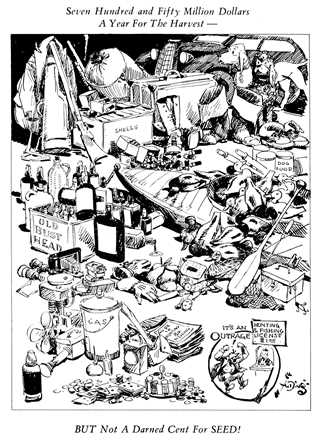

He was one of the most famous cartoonists of his time, syndicated in more than 100 newspapers, winner of two Pulitzer Prizes, a man known by common people and presidents alike. His work spanned all the important issues of the day, but he returned again and again to the theme of conservation of soil, water, timber, and wildlife. Darling led the movement to establish a nonpolitical state fish and game commission in Iowa, which the legislature created in 1931. Soon after, he was named one of the commission's original members.

In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Darling and the ecologist and philosopher Aldo Leopold to a committee charged with designing a program to rebuild declining waterfowl populations. Later that year, Roosevelt appointed Darling as director of the Bureau of Biological Survey (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). Just six days after Darling took office, a sweeping new funding strategy for waterfowl took effect—the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act, familiarly known then and now as the Duck Stamp Act. Every duck hunter in America was required to buy the $1 stamp for the 1934 hunting season.

The duck stamp was a badly needed boost for waterfowl funding, but, from a strictly practical point of view, it presented the leaders of the Bureau of Biological Survey with a nightmarish problem in logistics. As Darling remembered 20 years later: "It was touch and go to see whether we could get a design approved and then engraved and distributed before the opening of the fall hunting season."

Colonel Harold Sheldon, who was in charge of public relations for the Survey, was responsible for designing the stamp and getting it printed. Darling remembered that he "came to me waving the time schedule and with tears in his eyes said he didn't see how it could be done because nobody that he knew anything about had the faintest idea of what a design for a conservation Duck Stamp should include. Neither did I, but having spent most of my life making a cartoon every day, I figured there must be some way to get a Duck Stamp out rather quickly, so I took six sheets of cardboard and made six experimental sketches and delivered them next morning to Colonel Sheldon, explaining that they were only preliminary sketches and that if any one of them approached the specifications which the Bureau of Engraving might have I would redraw and refine the sketch."

A few days later, he asked Sheldon what progress was being made. According to Darling, Sheldon replied, "Oh, they selected one and the engravers are already at work on it."

Darling, the artist, was outraged that one of his preliminary sketches was being used for the stamp. "I could have murdered Colonel Sheldon and all of the Bureau of Engraving personnel and every time I look at the proof design of the first duck stamp I still want to do it," Darling remembered.

Somewhere in the scramble, the original sketch disappeared and has never been found. Knowing printers, I suspect that, on some dusty, poorly lit shelf in the bowels of a government storage building, some of the most valuable sketches in the history of wildlife art are waiting to be rediscovered.

That first year, 635,000 hunters bought duck stamps. Today, around 1.5 million duck stamps are sold every year, and revenue from those sales has contributed over $1 billion to wetlands conservation since 1934. By law, the proceeds from those sales go into the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund to be used specifically for the benefit of ducks, geese, and other migratory birds. Duck stamp funds have been used to buy more than six million acres of habitat. They've also been used to establish or expand more than 300 national wildlife refuges. Officials expect Storm's 2019 stamp to raise as much as $40 million for conservation.

Darling stayed less than two years with the Survey, but in that time he was instrumental in creating 45 new national wildlife refuges and protecting more than 1.5 million acres of habitat across the country.

Leopold defined the ultimate standard by which our treatment of the land and its wildlife should be judged. "A thing is right," he wrote, "when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise." The pursuit of integrity and stability is the day-to-day business of conservation, an effort that is often prosaic, more practical and technical than spiritual.

The study of beauty, Leopold's last element, is the work of the artist. Storm, Darling, and all the other painters whose visions of waterfowl have illuminated the duck stamp over the last 85 years remind us of the infinite color and grace that rise out of the untamed landscapes we protect and nurture. Beyond the many practical justifications for conservation, there is one undeniable aesthetic truth that may be the best reason of all for the work, a fact the artist captures for us all: Wild is beautiful.

COURTESY OF THE JAY N. 'DING' DARLING WILDLIFE SOCIETY

Darling was one of the best-known editorial cartoonists of his era. Much of his work dealt with wildlife, hunting, and conservation issues.

Get Your Duck Stamp Duck stamps are a required annual purchase for waterfowl hunters age 16 and older, and a current duck stamp grants the bearer free entrance into any national wildlife refuge that charges an entry fee. The 2019−2020 federal duck stamp goes on sale in late June. You can get yours at many post offices, sporting goods stores, through participating state wildlife agencies, and online at duckstamp.com.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy