The American Duck Hunter Part 2

As waterfowlers, we are facing a variety of challenges to our sport and the resources that sustain our hunting traditions

As waterfowlers, we are facing a variety of challenges to our sport and the resources that sustain our hunting traditions

By Dale Humburg, Mark Petrie, PhD, and Greg Soulliere

MY INTRODUCTION TO WATERFOWL HUNTING WAS A TRADITIONAL ONE. I TAGGED ALONG WITH MY DAD. HE GREW UP ON THE FARM AND STARTED OUT HUNTING DUCKS IN A SLOUGH IN THE PASTURE BEFORE MOVING ON TO THE MARSHES OF NORTHERN IOWA. HE HAD VIVID RECOLLECTIONS OF AUTUMN SKIES DARKENED BY MIGRATING WATERFOWL. I REMEMBER HIM TELLING ME, "MY GAD, DALE, WE USED TO HAVE FLIGHTS. FOR DAYS AT A TIME, MALLARDS WOULD FLY OVER ALMOST CONTINUOUSLY AND INTO THE NIGHT."

I HAVE ONLY VAGUE MEMORIES OF MY EARLIEST DUCK HUNT, BUT IT WAS ENOUGH TO HOOK ME FOR LIFE. WHILE I WAS GROWING UP IN THE 1950S AND '60S, DUCK HUNTING WAS A COMMON DENOMINATOR IN MY FAMILY THROUGHOUT THE YEAR. FIRST CAME THE SPRING DUCK MIGRATION, FOLLOWED BY DUCK-BOAT BUILDING THROUGHOUT THE SUMMER, ANTICIPATION OF THE SEASON ANNOUNCEMENT IN EARLY FALL, AND FINALLY GOING HUNTING EVERY WEEKEND AND BEFORE AND AFTER SCHOOL. I HAVE KEPT A HUNTING JOURNAL FOR MORE THAN 50 YEARS, AND IT CONTAINS A TREASURE TROVE OF CHERISHED MEMORIES AND USEFUL INFORMATION. I ONLY WISH THAT I HAD RECORDED EVEN MORE DETAILS.

Photo © BILLBUCKLEYPHOTOGRAPHY.COM

In the previous issue of Ducks Unlimited, we traced the long-term decline in the number of waterfowl hunters and changes in duck harvests over the past 60 years. In this article, we will focus on the experiences of individual hunters and how they might have changed since our fathers' and grandfathers' times. We'll take a look at changes in hunting access and find out whether public hunting areas are more crowded now than they used to be. We'll also explore whether harvest regulations have the same influence on hunting participation that they once had, and we'll examine harvest trends to see if hunters are as successful today as they were in the past.

Why are these questions important? In the 1970s we had more than 2 million duck hunters in the United States. Today, we have roughly half that number. Recruiting new hunters and retaining the ones we have is proving to be a major challenge for waterfowl managers and conservation organizations, including Ducks Unlimited. How people join our sport, and the barriers many face in doing so, have important ramifications not only for the future of waterfowling but also for the birds and their habitats.

When it comes to recruiting new duck hunters, there is perhaps nothing more important than access. All other considerations are secondary to having a place to put your boots in the marsh. But finding a reasonably good place to hunt is no small task. Even experienced hunters can struggle to find productive hunting spots, and for novices, it can be downright intimidating.

Photo © Ed Wall Media

There are three main types of hunting access for waterfowlers: public lands, including managed areas and other open lands such as lakes, rivers, and reservoirs; private duck clubs and leased lands; and those private, unmanaged lands we'll call "the back 40." Unlike duck clubs or leases, the back 40 has no dues, management costs, or waiting lists, but it offers hunters the chance to jump-shoot a teal or maybe decoy a mallard or two along a creek, beaver pond, or off-channel oxbow. A shotgun, a box of shells, and maybe a half-dozen decoys is all you need to hunt there. Youngsters might start hunting on the back 40 accompanied by a family member or maybe a buddy or two, and when they are old enough to drive and afford the gas money, they may venture farther afield in pursuit of more ambitious hunting adventures. The back 40 is the perfect place to nurture a budding interest in waterfowling and to introduce new duck hunters to the sport.

Unfortunately, opportunities to hunt the back 40 have declined precipitously since our fathers and grandfathers bagged their first ducks. From the mid-1950s through the mid-1970s, wetland losses in the United States averaged 550,000 acres per year. It was the most intensive period of wetland destruction in the country's history, brought on by better drainage technology, federal subsidies for converting wetlands to farmland, and a lack of wetland protection laws.

Fortunately, public lands expanded dramatically during the latter half of the 20th century. Between 1940 and 1990, the number of national wildlife refuges that provide habitat for migrating and wintering waterfowl increased from 62 to 210, adding 3 million acres of public land across the four flyways. States were also busy acquiring and restoring wetlands during this era, providing even more wildlife habitat and public hunting access.

Hunting opportunities on some private lands have increased as well. A national survey in the mid-1960s estimated that the United States had more than 5,000 duck clubs, encompassing 2 million acres. Since the early 1990s, private landowners have been able to enroll flood-prone lands into federal programs such as the Wetlands Reserve Program. In many instances, these Farm Bill programs have provided opportunities for landowners to manage their own "piece of duck heaven" or to lease these lands to hunters. In just 30 years, well over 2.5 million acres of wetlands have been restored on more than 10,000 tracts. Moreover, the practice of flooding rice fields after harvest has created new leasing opportunities for farmers and hunting opportunities for waterfowlers on more than 1 million acres.

Photo © SHARP-EYEIMAGES.COM

While hunting prospects on public lands and managed duck clubs and leased lands may have increased, opportunities on the back 40 have almost certainly declined. Because fewer Americans are growing up on farms where they might have access to such places, most of today's aspiring duck hunters must look to public lands, clubs, or leases to get their start-and they often need help from an experienced waterfowler. There are far fewer fortunate youngsters who can still wander the back 40 and "self-recruit" on their own terms.

The loss of hunters since the 1970s might lead us to assume that crowding has become less of a problem for many waterfowlers. However, a 2017 national survey provides a contemporary benchmark for hunter preferences and priorities, including their thoughts about crowding. More than half of the survey respondents cited crowding on hunting areas, hunting pressure, and a lack of public places for waterfowl hunting as moderate to very severe problems. Yet other studies show that the total number of days spent afield by duck hunters over the past 20 years has declined from more than 8 million to just over 5 million, reflecting the overall loss of hunters. This doesn't exactly square with the 2017 hunter survey and complaints about overcrowding.

How do we reconcile modern concerns about overcrowding with the fact that we have fewer hunters and more public land? Three of four waterfowlers who participated in the 2017 survey preferred hunting opportunities within an hour's drive of where they lived, and nearly half reported hunting public areas. Several studies, including the 2017 survey, have pointed to the importance of "hunt quality." Quality can mean different things to different hunters, but it is often associated with seeing lots of birds, low hunter densities, and perhaps ease of access. Well-managed public areas can provide most or all these things, but they rarely remain a secret, especially when they are located within a reasonable drive of population centers. The demand for hunting spots on such areas will always be high, even in the face of declining hunter numbers. Loss of the back 40, with its easy access and no crowds, has heightened demand for accessible public hunting. That said, there are still many public lands (managed and unmanaged) that offer a quality experience.

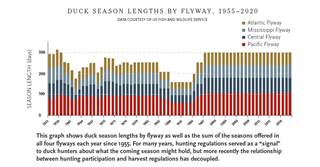

We've long assumed that changes in hunting season lengths and bag limits affect hunter participation. In August 1958, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) announced season lengths of 60, 70, 75, and 95 days in the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways, respectively. A year later, seasons were shortened in the eastern three flyways by 30 to 40 percent as waterfowl populations declined. By 1962, seasons as short as 25 days with a two-bird daily bag limit (including only one mallard) were the rule in the Mississippi and Central Flyways. The obvious signal those regulations sent to hunters was that fewer ducks would fly south and that hunting would be mediocre at best. That message was received loud and clear, and by the early 1960s duck hunter numbers had declined by half, compared to the mid- to late 1950s. But the message can also work in reverse. As waterfowl populations rebounded in the early 1970s and regulations were liberalized, many hunters returned to the sport.

For most of waterfowl management history, annual harvest regulations have served as the most important indication of what the coming hunting season might hold. For the modern-day hunter, that has changed. Beginning in 1995, the USFWS implemented Adaptive Harvest Management (AHM) as a way to objectively set duck hunting regulations and in the process learn more about the effects of harvest and habitat conditions on duck populations. AHM has streamlined the regulations-setting process by offering three basic choices for regulatory frameworks: restrictive, moderate, or liberal. Under AHM, harvest regulations have remained liberal for the past 26 years, so an entire generation of waterfowlers has never experienced restrictive regulations. Although duck populations noticeably declined in some of those years, AHM prescribed that liberal regulations should remain in place. That was a marked shift from previous decades, when even modest changes in duck numbers might prompt a change in harvest regulations.

Current evidence indicates that duck populations are influenced more by breeding success than by the number of birds harvested. As a result, waterfowl managers have become more comfortable with longer seasons, even when duck populations aren't booming. Consistently liberal seasons over the span of more than two decades under AHM appear to have changed the relationship between harvest regulations and hunter expectations. While this shift has undoubtedly provided hunters with more harvest opportunities, this has also meant that liberal regulations no longer generate the kind of excitement they once did.

Photo © Chuck and Grace Bartlett

Even during the days of highly restrictive harvest regulations, dyed-in-the-wool waterfowlers were not deterred-they hunted regardless of the season length or bag limit. That was obviously the case during the early '60s, when 1 million waterfowlers hunted ducks despite the most restrictive regulations ever. Six decades later, in 2017, one-third of hunters indicated "I'll hunt with any season length," and the same proportion said "I'll hunt with any size bag limit."

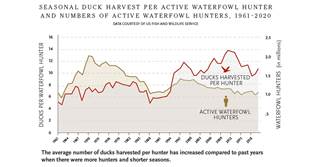

A favorite topic of discussion among waterfowlers, especially older ones, is what it was like back in the "good old days." But did our fathers and grandfathers really have better hunting than we do today? The two most obvious ways to measure hunting success are by average daily harvest and average seasonal harvest per hunter. Based on these criteria, many of our fathers and grandfathers were no more successful in terms of the number of birds they harvested than we are today. In fact, the average number of ducks bagged per hunter has increased since AHM was implemented in the mid-1990s.

Photo © Ed Wall Media

In part one of this series, we discussed the difficulty in recruiting new hunters and retaining hunters who might only buy a license once every few years or who hunt mostly when the news about duck populations is good. We referred to these waterfowlers as "casual" and "almost avid" hunters, respectively. Recruiting new duck hunters and keeping the ones we already have cannot be separated from the opportunity to hunt, and opportunity is all about time and space; in other words, having enough time to hunt and a place to do it. Although 26 years of liberal seasons have provided us with more days to spend afield, this has not stemmed the loss of hunters who cite "not enough time" and being "too busy with family or work obligations" as reasons for their lapse. While the waterfowl hunting community has always included casual and less-than-avid hunters, the time constraints faced by many today may make it more difficult to retain or reactivate these hunters than in the past.

Having a place to hunt is obviously important both for recruiting and retaining hunters, and the loss of the back 40 has put additional pressure on public lands to fulfill this role. Yet the popular public hunting areas on which novice and more casual hunters increasingly depend often suffer from overcrowding. Avid hunters who have the experience and equipment to take advantage of these public hunting opportunities typically fare better than beginners on the modern waterfowling landscape. Thus, the most effective way to recruit new hunters is for experienced waterfowlers to bring novice hunters along on their hunts.

Encouragingly, more than four in 10 respondents in the 2017 survey said they had invited someone who never had hunted before to join them on a hunt. Half of those indicated they had taken an adult friend (perhaps a casual or almost-avid hunter), while one in four took their own child or an unrelated child on their first hunt. Based on those responses, a considerable number of potential duck hunters are at least exposed to waterfowling each year. However, a single experience-even a positive one-isn't enough to recruit new waterfowlers or perhaps even to retain casual ones.

Photo © Ed Wall Media

Hunter recruitment and retention must be viewed as a long-term process that requires considerable assistance and encouragement from experienced hunters who have already acquired the knowledge, skills, and equipment to be successful. A social network is essential to provide the sustained support needed to mentor new hunters and reengage more casual hunters who have left the sport. Retaining a large base of avid waterfowlers will be especially important if duck populations fall to depressed levels and harvest regulations are restricted. If we lose half of the existing population of waterfowlers, which has happened in the past when restrictive regulations have been implemented, we would be left with just over 500,000 active duck hunters in the United States. Would that be enough to recruit the next generation of waterfowlers and reengage others when liberal regulations are reinstated? It is a sobering reality that the future of our sport is largely in the hands of today's waterfowlers. Do we care enough about our traditions to share our hunting areas with newcomers and make room for beginners in our blinds, including more women and those from diverse backgrounds?

Restoring and protecting wetlands and other key wildlife habitats is essential to maintaining waterfowl populations at healthy levels. And in that respect, Ducks Unlimited's work has never been more relevant. However, our mission now involves more than traditional habitat conservation work. Fulfilling DU's vision of "wetlands sufficient to fill the skies with waterfowl today, tomorrow, and forever" will require us to not only conserve enough habitat to support ducks but also to sustain large numbers of duck hunters. As in the past, we will need them to ensure a bright future for North America's waterfowl and their habitats.

Before his retirement, Dale Humburg served as DU's chief scientist and senior science advisor. Dr. Mark Petrie is director of conservation planning in DU's Western Region. And Greg Soulliere is regional science coordinator for the Upper Mississippi/Great Lakes Joint Venture with the US Fish and Wildlife Service. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy