Ducks at a Distance

This classic ID guide, first published nearly six decades ago, is still a go-to resource for waterfowlers

This classic ID guide, first published nearly six decades ago, is still a go-to resource for waterfowlers

Some hunters just know. They can look at a smudge in the sky, over the trees at 300 yards away, and identify a flying duck in three blinks of an eye. My buddy Ron Wade Jr., who guides on Currituck Sound, North Carolina, is one of them. He can sort out a gadwall from a wigeon at a ridiculous distance. He's not even stumped when a ring-necked duck is hanging out with a crowd of lesser scaup a football field's distance away. Press him on what he looks for, how he scrutinizes the various colors of various body parts, and he shrugs and says, I don't know, really. Been watching ducks all my life. How do you argue with that?

I'm not like Ron. As with duck calling, I'm somewhere between decent and pretty good at my ID skills, with an occasionally downright horrible day thrown into the mix. As many ducks as I've watched, you'd think I'd have it a little more dialed in. Am I looking for white on the speculum or the forewing? Is a wigeon larger than a gadwall? Does a bufflehead have a white patch above the eye, or is that a ruddy duck? I'm too easily stumped.

Identifying ducks and geese on the wing is a crucial skill given today's finely parsed bag limits. You need to be sure of what you're shooting at. To the novice, waterfowl identification must seem a mystifying alchemy, a knot of good field skills wound up with instinct and informed guesswork, if not a bit of downright hooey.

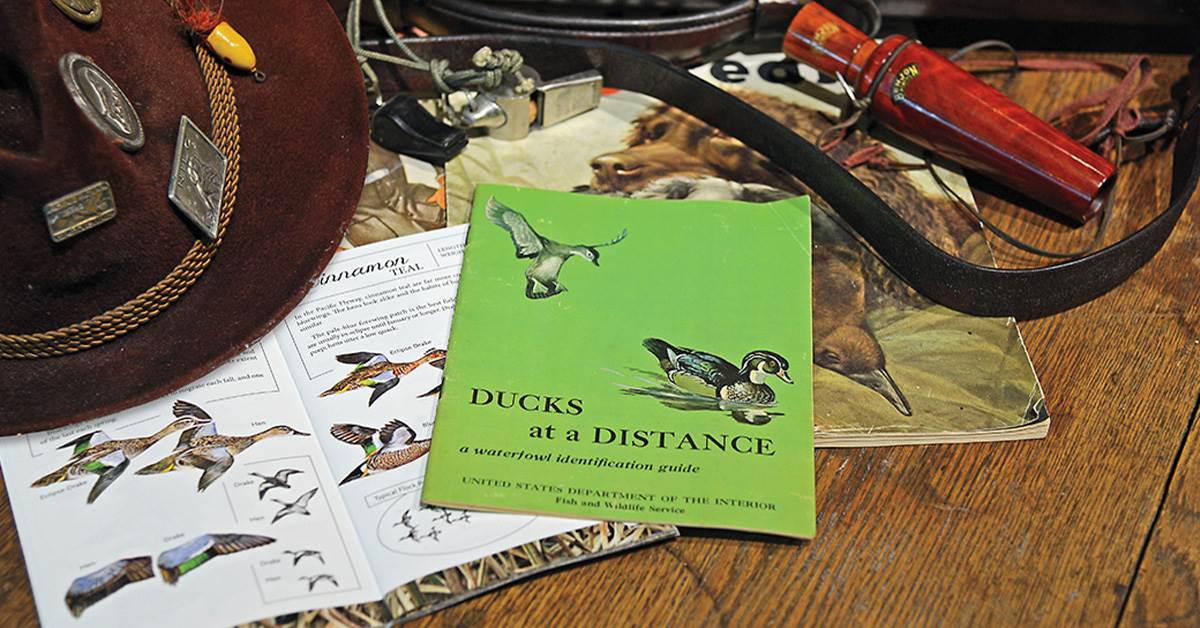

It's a skill that can be honed, though. There are tons of online aids, but when I'm trying to decipher a tough-to-call duck, the first name that comes to mind is Bob Hines and his beloved little booklet Ducks at a Distance. This pocket-sized made-for-hunters field guide is a gem.

Hines never had formal art training, but in 1939 he was hired as a staff artist for the Ohio Division of Conservation and Natural Resources. Later he would enjoy a long career as staff artist for the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Hines painted the 1946 federal duck stamp, illustrated Rachel Carson's bestseller The Edge of the Sea, and designed the first U.S. postage stamps to feature American wildlife.

The Government Printing Office first published Hines' ID booklet in 1963, and it has since sold more than two million copies. It was reprinted by the Canadian Wildlife Service, the Southwest Natural and Cultural Heritage Association (where my copy was published), and a handful of other organizations and agencies. Gazillions of these things were given away. I can't say for sure where I got my copy, but it's a good bet I picked it up at a DU banquet early in my duck-hunting career.

I can be in a blind and spot a flock of ducks a half-mile away, and instantly my mind recalls Hines' pen-and-ink drawings of duck flocks. Each was labeled "Typical Flock Pattern" and showed a tight V of canvasbacks on the wing, for example, or a scattershot of green-winged teal that appear to be a split second from corkscrewing off the page. Hines knew what hunters needed. He placed eclipse drakes and hens side by side and detailed specific field marks of ducks flying overhead. Compared to the works of more modern illustrators, Hines' ducks are decidedly old-school. But to me, the paintings seem suffused with character and details only a hunter would know. They are the ducks of my earliest mornings in a swamp and my most recent dawns in a marsh.

Even today, in the breaking light of dawn, I hear woodies whistle overhead, and I visualize Hines' wood duck drake. It drifts across a right-hand page, head cocked slightly downward as if eyeballing my decoys far below. Its wings are forever cupped. Its jaunty head crest is perpetually compressed. That woodie is on an eternal glide across my imagination, dropping down to a landing it will never make.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy