Before You Shoot: Mastering Waterfowl Identification

Here’s how to identify ducks in the air and on the water

Here’s how to identify ducks in the air and on the water

By Teresa Milner

Ducks, geese, and other waterfowl don’t carry ID cards. It’s your job as a hunter to know which species you’re hunting and the regulations governing them. Ready to learn how to improve your duck identification skills? Read on!

If you are hunting deer, there aren’t many other species that you would likely mistake for your quarry. But waterfowl are a whole different deal. There are dozens of duck species in North America. One species can closely resemble another, and male ducks and female ducks of the same species can sometimes look a lot alike. Add flat lighting, lots of birds on the water or in the air, speed, and the thrill of the hunt, and proper identification can become downright diabolical.

Strong waterfowl identification skills are a crucial part of being an ethical and experienced hunter, and they help ensure the long-term health of waterfowl populations. “Harvest regulations, including both season lengths and bag limits, are tied to the population status of different waterfowl species,” says Dr. John Coluccy, director of conservation planning for DU’s Great Lakes/Atlantic Region. “When a population of a particular species has declined below a certain threshold, you’ll see more restrictive regulations put in place for that species. That might include a reduced bag limit or fewer days in the hunting season.”

Waterfowl managers tighten or loosen restrictions to help populations of certain species recover or, conversely, to help reduce numbers to a more manageable level. Because many waterfowl species are migratory and cross international borders, hunting regulations are established under an international treaty. The US Fish and Wildlife Service and state representatives in each of the four flyways develop harvest regulations cooperatively. They determine the seasons and bag limits to ensure healthy populations of each species. It’s a great idea from a wildlife management perspective, but it requires more effort by hunters to understand and follow the regulations. That starts with knowing your ducks by sight and sound.

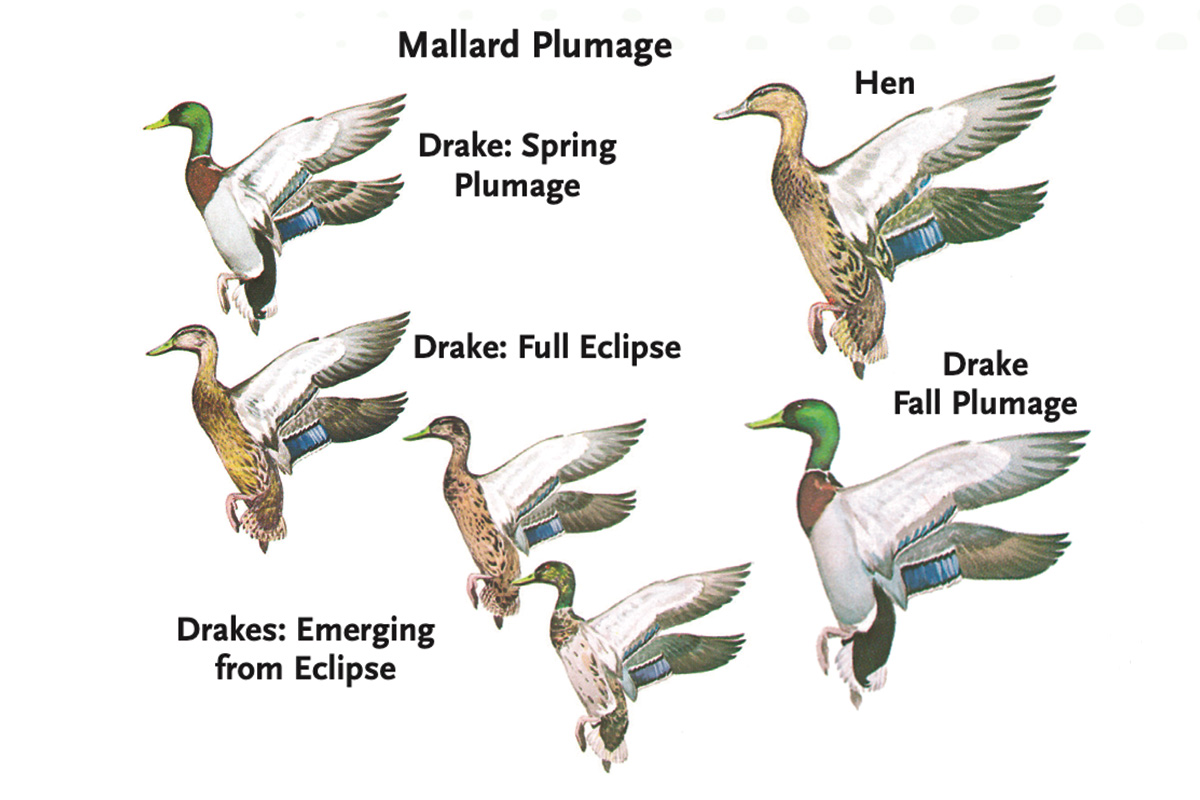

The mallard is a good example. “Bag limits allow you to harvest more drakes than hens,” Coluccy says. “So in some cases it’s important for you to be able to identify not only the species of duck, but also to distinguish males from females.”

Proper waterfowl identification helps keep you legal and helps maintain the health of waterfowl populations, especially less numerous species. It can also be a lot of fun. Sometimes just observing birds and identifying all the different types of species is a reward in and of itself.

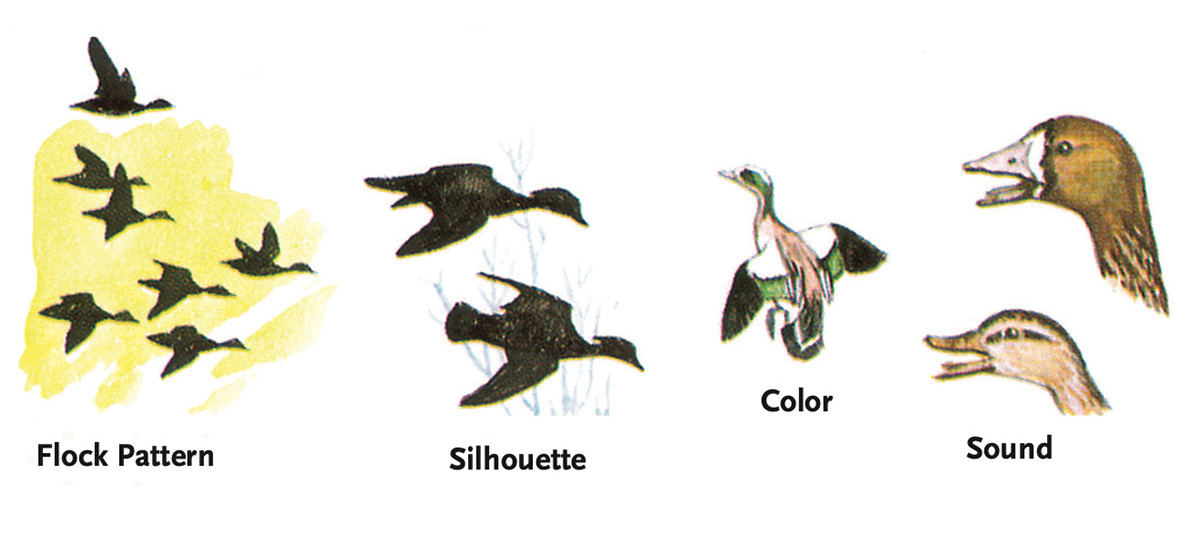

Shape, sound, color, behavior, habitat, and range are all clues that can help you identify a duck’s species and sex. But with so many things to evaluate, where should you begin?

Color

Color is a telltale characteristic, especially when it comes to drakes. Hens usually aren’t nearly as showy. Especially from late fall through spring, drakes of most species of ducks have distinctive plumage that is readily identifiable. For example, drake mallards have an iridescent green head and white neck collar. Drake cinnamon teal have that distinctive cinnamon-red head, breast, and belly.

Look for the White

Another common method for identifying ducks by plumage is to “look for the white.” This is one method promoted by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The white patches of a duck are easier to spot at a distance than some other characteristics. For example, the drake American wigeon has a distinctive white patch on the leading edge of its wing that is very visible during flight. Drake canvasbacks have a white belly and back. Learning where the white is on different species is a great way to improve your identification skills.

Wingbeats, Calls, and Silhouettes

Hunters are often faced with the challenge of identifying birds in flight. How do you determine who’s who when the ducks are cruising by at a distance or in low light conditions? You can start by learning to recognize wingbeats. A ruddy duck, for example, has very small wings in relation to its body size and must beat its wings rapidly to stay in flight. A mallard, on the other hand, has relatively large wings and beats those wings more slowly. When conditions make other methods of identification difficult, you can also learn to identify and listen for each species’ distinctive calls and recognize their body shapes or silhouettes.

Other Clues

Most people want to jump right in and start looking at plumage, but there are times when plumage is the hardest clue to decipher, such as in early fall, when the drakes haven’t yet developed their bright colors. In those instances, Coluccy advises starting with broad characteristics and narrowing it down. Start by knowing which species might be in your area, which tend to use the kind of habitat you’re hunting in, and which birds are likely to be present at a particular time of year. “Where you are in the world dictates what kind of waterfowl are typically there or not there,” he says. “The types of habitat are also connected with certain types of species.”

Wood ducks, for example, prefer different types of wetlands than redheads. Wood ducks are found in riparian areas, wooded swamps, and freshwater marshes. Redheads, by contrast, are usually seen in non-forested areas of open water.

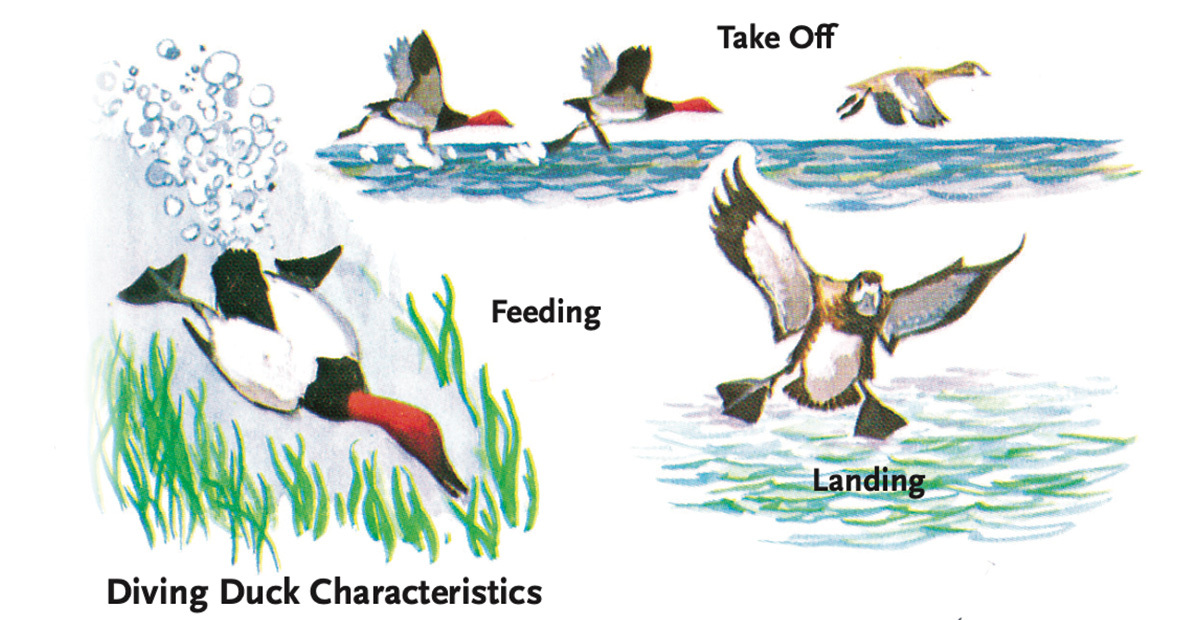

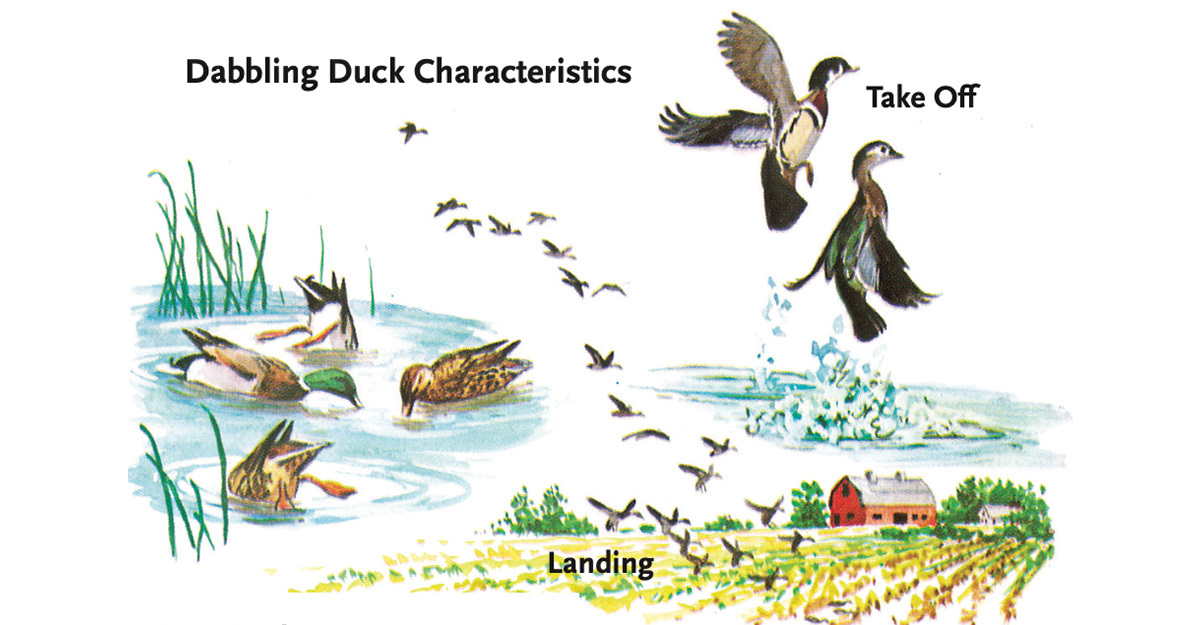

Next, Coluccy advises looking at where the ducks are on the water and how they are foraging. “If they tip up, if their butt is sticking up in the air and their feet are splashing around, those are dabbling ducks, which are also called puddle ducks,” he explains. Ducks that are diving or submerging in deeper water are diving ducks. “Once you determine whether you’re looking at diving ducks or puddle ducks, you immediately narrow the field.”

Ducks also sit on the water differently. Dabbling ducks sit a little higher on the water and have tails that are more upright. Diving ducks ride a little bit lower with a tail that flattens toward the water instead of rising upward.

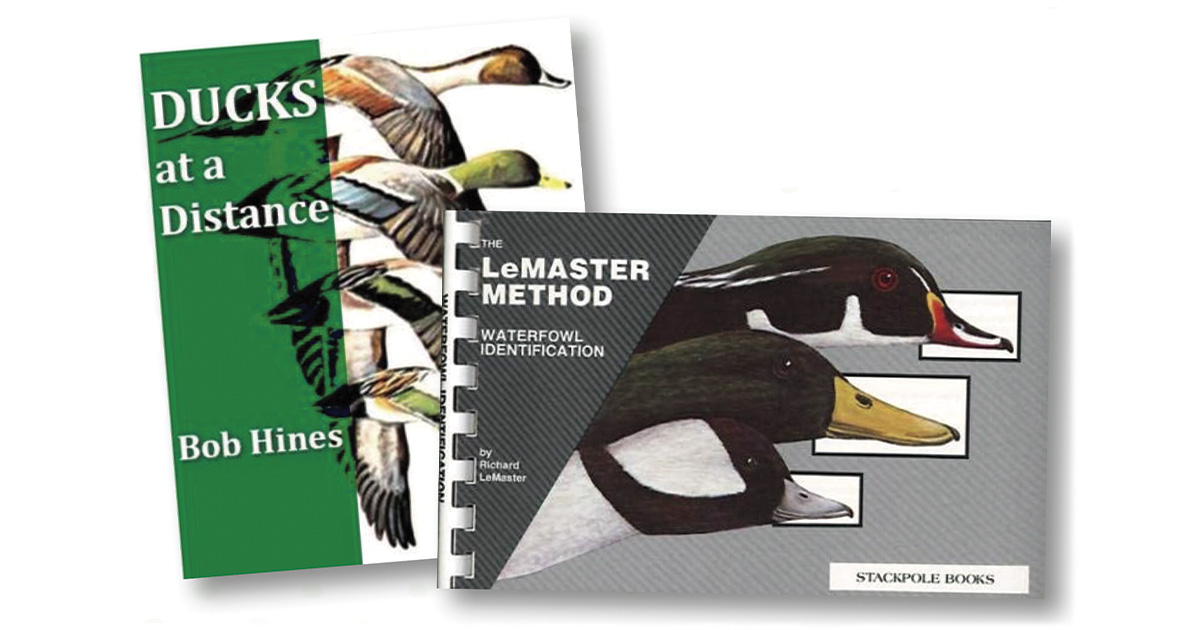

No true duck hunter learning the craft should be without a great ID guide. Coluccy recommends Waterfowl Identification: The LeMaster Method, by Richard LeMaster, and “Ducks at a Distance,” a pocket guide available from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Any guide that gives you photos or illustrations for ducks found in your area will work, he says. Websites, videos, and recordings can also help. DU has a comprehensive waterfowl identification page on its website at ducks.org/hunting/waterfowl-id/.

If you need more interactive, step-by-step advice, check out the “Be a Better Birder: Duck and Waterfowl Identification” course available through the Cornell Lab Bird Academy. This paid course features videos, photographs, and quizzes to test your newfound knowledge.

Books and videos will get you partway there. But there is simply no substitute for firsthand experience. If you want to improve your skills, you need to get out in duck country. Coluccy says his skills came from years of spending time in the marsh and watching birds.

“When I first started going hunting with my father, I spent a lot of time in the blind without a gun, learning the birds as they came in,” he says. “When you get them in hand, take a good look at them. Look at the bill, the shape of the body and the forehead. Where are the feet placed? What’s the color of the bill? Spend time on the water and in the blind with someone experienced at waterfowl identification. What colors do you see? Where are the birds on the water? How are they riding on the water? What do they sound like?”

Coluccy also recommends keeping an ID guide with you and practicing at times when you aren’t hunting. “Stop at a wetland with a spotting scope or a pair of binoculars and just take a look. Have your ID guide with you. Just practice. Before you know it, you’ll learn to identify them!”

The best hunters know when to take the shot and when to hold their fire. If you aren’t confident in your identification of the species and sex of the bird in the moment, it’s best to let it fly on by. It’s the right thing to do. You’ll also avoid fines and help keep duck populations strong and healthy well into the future.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy