History of the Semiauto

More than a century of creative design and skillful engineering led to the development of today’s autoloading shotguns, which are more durable and dependable than ever

More than a century of creative design and skillful engineering led to the development of today’s autoloading shotguns, which are more durable and dependable than ever

Semiautomatic shotguns have become so common today that the shuck of a pump gun—at least in the duck blind—threatens to join the clack of a typewriter and the jangling ring of a telephone in the catalog of forgotten sounds. Pumps and double guns will always have a place, but the semiauto has reached such a high level of reliability and versatility that it is now the overwhelming favorite of duck and goose hunters.

John M. Browning patented the first semiauto shotgun, the Auto-5, in 1900. The original Auto-5 delivered five shots as fast as you could pull the trigger, and it turned out to be an extremely reliable gun in all conditions. Browning had already invented a successful gas-operated machine gun and some semiauto pistols, but a semiautomatic shotgun was trickier to design than a rifle, pistol, or machine gun. Military weapons use a standardized cartridge, but a sporting shotgun has to work with a wide range of ammunition. You can design a shotgun that will cycle light loads, but if you shoot heavy loads through the same gun, the bolt will whip back so fast that it will batter the receiver and wear out parts. Likewise, you can tune a shotgun for magnum loads, but it won’t cycle field loads. Controlling the bolt velocity is crucial to making a semiauto that will last and function reliably, and the problem confounded Browning as he worked on the gun.

John M. Browning test-fires a prototype of the .50 Browning Heavy Machine Gun.

Ultimately, Browning built three different experimental shotguns and settled on the long-recoil model as the best solution. In a long-recoil action, the barrel moves with the bolt for the entire length of the shell. The bolt locks at the rear of the receiver and the barrel moves forward on its own spring, with the empty shell ejecting on the forward stroke before a carrier lifts the next shell into place.

In Browning’s design, a pair of friction rings on the magazine tube could be set by the gun’s owner to provide the right amount of resistance to the barrel spring for use with light or heavy loads. By 1899 he had a gun that satisfied him. He just had to find someone to make it.

Browning had sold a number of his designs to Winchester outright, but he asked for royalties for the Auto-5, precipitating a rift with Winchester. Remington also refused him—although they would soon license the design as the Model 11, as would Savage with the 720 some years later. So Browning took his gun to Fabrique Nationale in Belgium, where it would be made until the 1970s (with a break during World War II, when Germany occupied Belgium) before production moved to Japan for another 20 years.

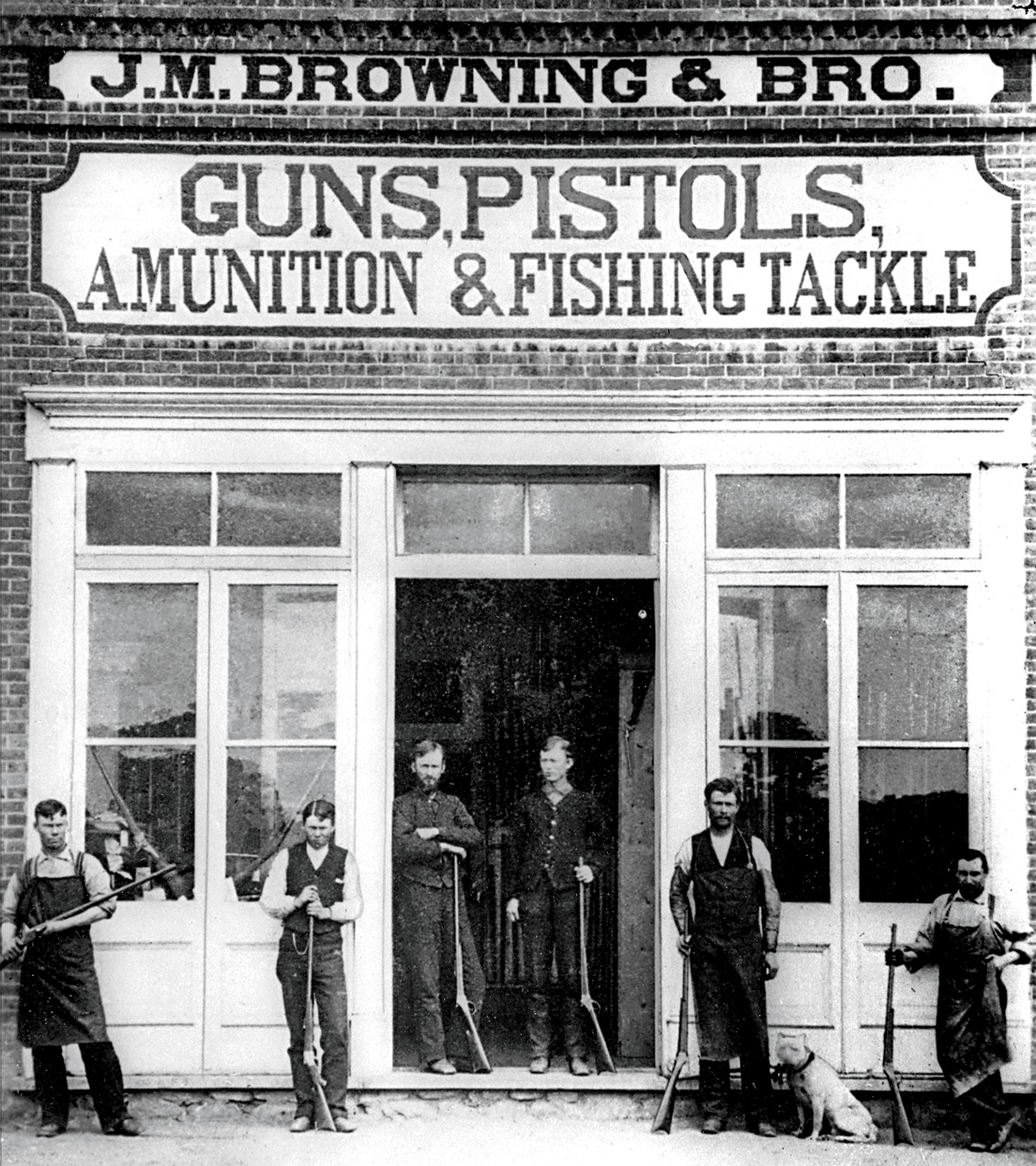

The building in Ogden, Utah, where Browning and his brother, Matthew Sandefur Browning, took over their father’s gunsmithing business in 1878 and began designing and building guns that would go on to revolutionize firearms manufacturing.

At the same time that Browning was inventing the Auto-5, Carl Sjögren designed a semiauto shotgun in Sweden. The Sjögren Normal Automatic was a strange-looking gun with a massive bolt/breech block that made up the entire top of the receiver. The bolt held in place for an instant as the gun recoiled, locking up and also compressing a spring inside. The spring then moved the bolt back, ejecting the empty and picking up a new shell. The gun was only made for a short time, but its operating system, which we now call inertia, would become popular with waterfowlers years later.

Another unsuccessful gun, Winchester’s Model 1911 SL, makes an interesting footnote to the Auto-5 story. After rejecting Browning’s gun and then witnessing its success, Winchester decided to make a semiauto of its own, tasking its engineers to design a gun that didn’t infringe on Browning’s patents. In place of Browning’s friction rings to slow the bolt, the 1911 had only a pair of sacrificial and not particularly effective fiber buffers to cushion the impact of the barrel slamming backward. Unable to use the patented bolt handle, 1911 SL designers knurled a section of the barrel to be used as a handgrip. Enough 1911 SL owners shot themselves by setting the butt on the ground and leaning over the muzzle to push down on the barrel while loading the gun that it earned the nickname “widow maker.” Only about 83,000 were made.

Early semiauto models like the Auto-5 became popular with waterfowlers.

The first of anything isn’t always great, but the Auto-5 was. There are still some duck hunters who believe that nothing made since has improved on it, and the Auto-5 remained the last word in autoloader design for 50 years. When Browning’s patents expired in 1947, Franchi introduced a lightweight, humpbacked, long-recoil shotgun called the AL-48. Remington replaced its licensed version of the Auto-5 semiauto, the Model 11, with the 11-48, marking a step forward in versatility. The 11-48 came with a self-adjusting friction ring that allowed you to shoot light and heavy loads without having to remove the barrel to flip the rings.

The 1950s saw Browning and Winchester experiment with short-recoil guns. The Browning Double Automatic and Winchester Model 50 had their followings, but they would not change the course of semiauto design the way gas guns would. In a gas-operated gun, a small amount of expanding gas is bled from the barrel and pushed against a piston attached to a linkage that then opens the bolt. World War II firearms like the M1 Garand proved that gas-operated small arms could function reliably under extreme conditions. And gas guns had the advantage of soft perceived recoil—a result of the gun’s moving parts storing and then releasing recoil energy, which lengthens its pulse and transforms a sharp kick to a firm shove.

In 1956 the first gas-operated semiauto shotgun, the J.C. Higgins Model 60, became available through Sears Roebuck stores. At the same time, Beretta was finishing up an unrelated Model 60 gas gun of its own and followed with the Model 61 soon after. Remington’s Model 58, introduced shortly after the Higgins Model 60, accommodated a wide range of heavy and light loads by means of a dial on the magazine cap, which adjusted the amount of gas reaching the action. Remington improved on the 58 with the 878 Automaster, which shot all 2 3/4-inch loads without adjustment.

In 1963 the semiauto that turned Americans into gas gun shooters arrived when the Remington 1100 replaced both the 58 and the 878. Among the first guns designed with the help of computers, the 1100 had the soft recoil of other gas guns and was much more reliable. The 1100 was an immediate success, and over 60 years later it’s still in production and still among the softest-shooting gas guns available.

Shortly after the 1100 appeared, Beretta introduced a successor to the Model 60 and Model 61. The new model, the 300, kicked off a series of autoloaders that many believe to be the best gas guns ever made.

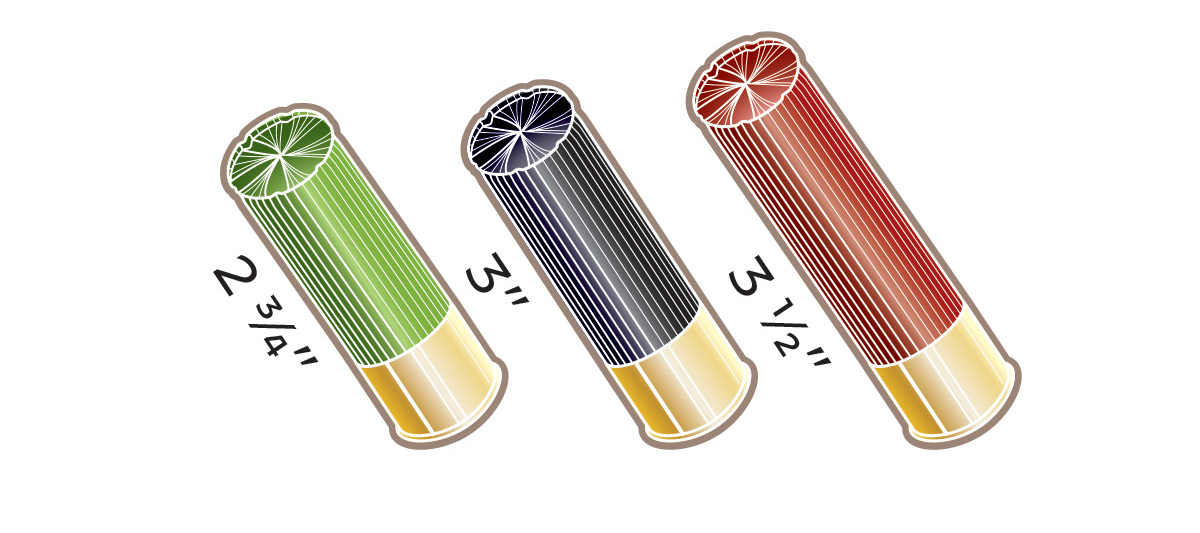

Gas guns like the 1100 or the early Beretta 300 series models could shoot all 2 3/4-inch loads without adjustment, but if you wanted to shoot 3-inch magnums you needed a 3-inch barrel with ports designed for heavier loads. The breakthrough all-load guns began to appear on the scene in the mid-’80s, when Smith & Wesson imported the Super 12, a Japanese Howa that could shoot 2 3/4- and 3-inch shells interchangeably. It featured a “self-metering” gas relief valve that opened under high pressure from heavy loads to vent excess gases but stayed shut when the gun fired light loads. Remington’s self-metering 11-87, essentially an 1100 with a redesigned piston ring, followed shortly thereafter, redefining the state of the autoloading art. Now you could buy one gun that functioned with everything from 1-ounce target loads to 1 7/8-ounce goose loads without any adjustment or barrel switching.

Not long after gun makers had solved the problem of designing a shotgun that could shoot 2 3/4- and 3-inch loads interchangeably, the 3 1/2-inch shotshell appeared. In 1988 Federal and Mossberg collaborated on a longer 12-gauge shell that could hold bigger payloads of steel shot, and they also designed a new gun, the Mossberg 835 Ulti-Mag pump, to shoot them.

The advent of 3 1/2-inch shells meant that semiautos needed to handle an even wider range of ammunition, and that engineering challenge presented an opportunity for a little-known Italian gun maker. The Benelli family had moved its motorcycle factory from the city of Pesaro to the town of Urbino in the 1960s. Avid hunters and shooters, the Benellis had made guns for themselves for years, and the move to Urbino sparked a relationship with Bruno Civolani, an engineer who designed shotguns on the inertia principle first seen on the Normal Automatic. It was then that Benelli became a gun maker.

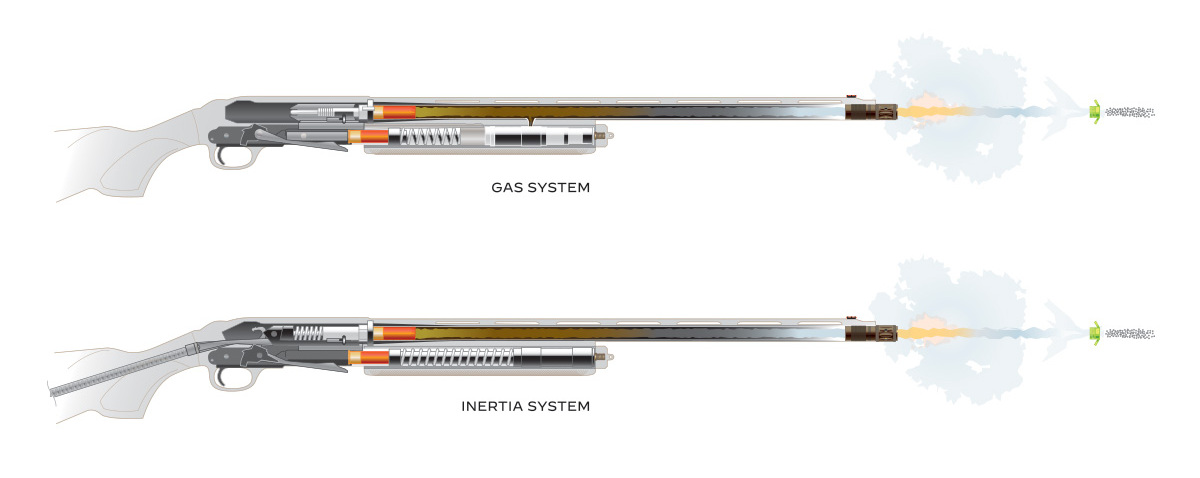

Gas guns use a small amount of gas from the barrel to drive the bolt back and eject the spent shell. A spring returns the bolt, picking up a fresh shell from the magazine. Inertia guns depend on a much simpler design in which the bolt briefly remains in place as the gun recoils and a spring inside the bolt compresses, sending the bolt back and ejecting the empty shell.

In the 1980s Heckler and Koch began importing Benellis to the United States, but the brand didn’t catch America’s attention until 1991, when Benelli unveiled the first 3 1/2-inch semiauto. Controlling bolt velocity isn’t as critical with inertia guns as it is with other semiauto systems because the bolt stays in place as the gun recoils, then moves back as its internal spring decompresses. It’s the spring, not the recoil or the amount of gas in the action, that drives the bolt, so the speed stays under control. All Benelli had to do was create a new version of its Black Eagle shotgun, which they called the Super Black Eagle.

The gun caught on, and hunters soon found that the ability to shoot any shells from 2 3/4 to 3 1/2 inches was just one of the SBE’s attractions. It was also light and slim, with no gas-system parts adding bulk to the fore-end. It stayed cleaner longer, because it didn’t bleed gas into the action, and the inertia system kept working under the worst kinds of waterfowling conditions. The SBE became the prestige gun among waterfowlers, and inertia became an increasingly popular alternative to gas.

Making a gas gun that could shoot all loads required more than stretching the action from 3 to 3 1/2 inches. Browning engineers worked to convert the Gold semiauto into a 3 1/2-inch gun, and early prototypes suffered battered receivers and broken bolts and bolt handles. Stouter parts and better recoil buffers tamed 3 1/2-inch shells, and after some early growing pains, the Gold became a reliable hunting gun. Browning spun it off as the Winchester Super X2 while other makers responded with 3 1/2-inch gas guns of their own. Beretta’s Xtrema and A400 models carried on the legacy of the 300 series, while Mossberg’s 935 put a 3 1/2-inch gas gun within the budget of almost any hunter. Remington, having twice set the standard in gas gun versatility with the 1100 and the 11-87, had to play catch-up in the 3 1/2-inch gun race, finally introducing a solid entry with the VersaMax in 2010.

As reliable as inertia guns are, the design has one nagging flaw: it’s easy to bump the rotary bolt out of battery. If you’re trying to be stealthy by closing the bolt quietly, or if you snag the bolt handle on something, your inertia gun might make a quiet click instead of a loud boom when you pull the trigger. Such misfires happen rarely, but always at the worst time.

Benelli solved the problem in 2014 with the Ethos, the first gun to feature the company’s Easy Locking Bolt. It took only the addition of a spring and detent to cure the infamous click. Located at five o’clock on the bolt body, the detent applies rotational pressure to the counterclockwise-rotating bolt head. It’s just enough to nudge the bolt into battery if it’s bumped or eased shut. Retay, a Turkish gun maker that entered the US market in 2017, offered guns with its own Inertia Plus solution from the beginning. The Easy Locking Bolt has since spread throughout the Benelli lineup, and other inertia gun makers will need to find their own solutions to keep up.

The 3 1/2-inch 12-gauge was originally invented to deal with the hull-capacity problems created by steel shot. Because steel is light, relative to lead, steel pellets are built larger, and you can only fit a limited number of those large steel pellets into a 3-inch 12-gauge hull. The comeback of bismuth and of tungsten-iron ammunition, both of which contain smaller pellets that are denser than steel shot, means that huge hulls, and even 12-gauges, are no longer completely necessary for many waterfowling situations.

American shooters love small-bore shotguns, and interest in downsized duck-hunting guns has surged, with new semiauto models leading the way. Browning’s A5 Sweet Sixteen 16-gauge created a stir with its introduction in 2017. It was light, it looked like the old classic, and it combined nostalgia for the old Auto-5 with Browning’s take on the popular inertia design. The 20-gauge version gained popularity as well, once hunters saw what it could do when loaded with bismuth or tungsten-iron ammunition.

Two years ago, the introduction of the Super Black Eagle 3 and A400 in 3-inch 28-gauge added an entirely new option for semiauto shooters to consider. Loaded with denser-than-steel ammunition, the 3-inch 28 is more than capable for birds over decoys, and the guns have the light weight and trim lines that many shooters prefer.

With 3 1/2-inch gas guns more or less perfected, with small-bore offerings increasing, and with Benelli’s patents having expired in 2006, which allowed other manufacturers to offer inertia guns, it’s tempting to say that in the 21st century, semiauto development is all over but for the tweaking. The top-of-the-line guns run longer between cleanings, malfunction less, and shoot a wider range of loads than ever before. Shim kits let you adjust their fit. Recoil reduction systems lessen the kick and allow guns to be built lighter. Cerakote and other coatings protect them from the elements.

And while you can now pay close to $2,000 for a semiauto, there are good gas and inertia guns to fit almost any budget. The quality of Turkish-made semiautos continues to improve, and guns like the Winchester Super X4, Tristar Viper, and Beretta A300 offer a lot of gun for not too much money. It’s possible that another genius could come along and revolutionize semiauto design, but it’s hard to imagine how the guns could get much better than they are now, more than 120 years after John Browning gave us the Auto-5.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy