Origins of the Autoloader

A century of innovation has made the semiauto America's favorite duck gun

A century of innovation has made the semiauto America's favorite duck gun

By Phil Bourjaily

In recent years, the autoloader has become the shotgun of choice for most waterfowlers. Its advantages include three quick shots, a reduction in recoil, ever-increasing reliability, and ease of maintenance. Here's a look back at the almost 120-year journey from the earliest autoloaders to the very latest.

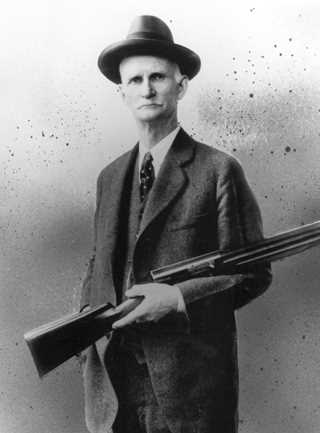

John Browning chose a long-recoil action when he designed the first semiautomatic shotgun in 1900. His original A-5 works like this. Recoil drives the barrel and bolt back the full length of the shotshell into the receiver. The bolt stays back briefly as the barrel moves forward, and the ensuing action clears the fired shell and loads a fresh round into the chamber. Browning's ingenious design was also featured on the Remington Model 11, the Savage 720, and the Franchi AL-48. These guns were so far ahead of their time that they dominated semiauto design for the next 60 years.

Around 1900, a Swede named Carl Sjögren made the first inertia-operated shotgun. Inaptly named the "Normal," this very odd-looking gun was manufactured in Denmark. While it presaged the inertia guns to come, the Normal is little more than a footnote in shotgun history.

It wasn't until the 1950s that autoloader designers came up with new ideas. Drawing on wartime advances in gun design, manufacturers made guns that operated on short-recoil actions, floating chambers, and expanding gases bled from the barrel to drive the action. This latter innovation became the most important, and in 1956 Beretta introduced its gas-operated Model 60. Coincidentally, the J.C. Higgins Model 60 gas gun (no relation to the Beretta) became available at Sears, Roebuck and Company the same year.

Remington entered the gas semiauto market with the Model 58 and the 878, but the gun that established the gas semiauto was the Remington Model 1100. Introduced in 1963, the Model 1100 was much more reliable than its predecessors and became an instant success. At about the same time, an Italian engineer named Bruno Civolani designed the first modern inertia gun, which featured a two-part bolt with a stout spring that compressed upon recoil before throwing the bolt back and opening the action. Civolani partnered with motorcycle maker Benelli to produce this state-of-the-art gun in 1967.

Fast-forward 20 years to the next breakthrough, the pressure-compensated piston. This innovation, which was developed by Remington and Japanese maker Howa in 1987, allowed a 3-inch-chambered gas gun to cycle a wide variety of 2 3/4- and 3-inch shells without switching barrels or making other adjustments. More "all-load autos" followed, including Beretta's 390 and Browning's Gold. In the 1980s, Benelli introduced the M1 Super 90, adding a rotary bolt to the inertia design, further improving the gun's legendary ability to shoot in the worst conditions. Also, gun makers started including accessories such as choke tubes and shims, which allowed shooters to customize their semiautos to improve fit and versatility.

Finally, with the advent of steel shot and the development of the 3 1/2-inch 12-gauge, engineers struggled to solve the problem of making guns that could handle everything from target loads to 3 1/2-inch turkey and goose loads. They soon learned that it wasn't enough to simply stretch a 3-inch gun to shoot 3 1/2-inch shells; the gun had to be built for the stresses of very heavy loads. Benelli struck first with the inertia-driven Super Black Eagle, and gas guns with improved gas-compensation systems followed. These guns were so successful that the 3 1/2-inch semiauto has become the flagship model of every gun maker's lineup.

Photo © Courtesy of Browning Arms

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy