Northern Hospitality

On his first trip to the Canadian prairies, a young hunter and his retriever learn lessons that last a lifetime

On his first trip to the Canadian prairies, a young hunter and his retriever learn lessons that last a lifetime

By Christopher Smith

I’d never seen that much wheat. Hell, I’d never seen that far before. Someone once told me that on the prairie, a man could see to the bend of the planet. Speeding along the Saskatchewan countryside, watching a harvest moon loom large and rise to the last light of day, I understood, at least a little. There was simply nothing to block my vision. No buildings. No cars. No people. Just wheat, and time to think.

The truck radio never worked well, even when reception was decent. Out here, it was useless, and the quiet lulled me into a calm, trancelike state, interrupted only by occasional snores from the backseat. Those snores came from Ruby, my new duck hunting buddy, curled up on an old quilt that had once belonged to another dog. Ruby knew very little about ducks yet. I’d picked her up in haste four months earlier from a breeder friend who told me my money was no good. Through more tears than words, I shook his hand—he’d sadly been there before, sifting through the train wreck created when a dog tragically dies before her time.

In April, Mags, a black Lab still very much in her prime, bounded up the snowy stairs off our deck—like she’d done a thousand times in her seven years—and slipped. When she let out a sickening yip, I knew that everything had changed. It was a knee injury. It was fixable, though unbelievably expensive, especially for a young married couple. So we gave it a try, with hopes for only one missed season and a return to active duty the following fall. But during the surgery a blood clot killed her, along with a good portion of my happiness.

Turning depression and mourning into an anxious search to fill that painful chasm, I checked with a buddy to see if any pups remained from his recent litter of 10. One diminutive yellow female was all he had. Leftovers aren’t usually a desirable choice, but my wife and I were elated to pour our grief into another furry life. I found out weeks later that my friend had kept her as his pick from the start but gave her up without hesitation. Some guys are like that.

Sadly, the new pup hadn’t yet filled the void. Even though I’d inherited Mags from my mom and dad, we developed a bond I thought I’d never share with another hunting dog. But if Ruby was going to be anything like her, that first season was crucial, and I had to give her as many chances as possible even though our normal spots and my shooting ability would probably yield few birds. Luckily, my old man had it figured out.

Dad recalled a hunting partner who, during their annual Hun and sharptail roundup, would ramble on about a Saskatchewan couple he’d met while hunting up there. They owned land littered with potholes and had access to many more through a network of family and friends. Dad’s friend spoke enthusiastically about their “salt of the earth” hospitality, so I made a phone call to meet and get directions, and nervously felt like I held a winning lotto ticket.

The trip along the Hi-Line—good old Highway 2—from northern Michigan was my first solo adventure of any length. Hunting trips always involved Dad, who saved and bartered when I knew he couldn’t afford them. He was evidence of how a sporting life yields riches far beyond the reach of money, and he seemed desperate to impart that love to me, or at least provide the opportunities.

There were quail hunts in Texas and Arizona, the Midwest for pheasants, Nebraska sharptails, and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula for grouse and woodcock—and all on an outdoor writer’s salary. I’d expressed interest in waterfowling after reading Nash Buckingham and Gene Hill, so Dad, an occasional duck hunter, introduced me to a friend who had all the accoutrements—decoys, boat, dog, experience—and then watched his son become an addict overnight. During the following years, he’d come along to shoot the odd mallard or bluebill, though his advice centered more on how not to drown than how to shoot a duck, which thankfully paid off a few times.

But his body could no longer tolerate sitting in cold boats or slogging through muddy marshes, and the long trips he once relished now seemed overwhelming, not only to plan, but to execute. All of this coincided with the look in my eye that said I was ready to break free. I was 24 and wanted the test—needed it.

So he told me to go west alone, to Canada, where ducks are made and fly by the thousands, before young kids could tie the homesick knot around my neck. More importantly, he knew that the grief I’d been sorting through would diminish if my attention was on Ruby and ducks. So I took off on the last day of September, driving toward a destination with only a name and vague directions to a prairie farmhouse where friends of Dad’s friend waited.

After 20 hours and a couple of pit stops for naps and gas, exhaustion was replaced with anticipation when I crossed the border into Canada and entered a monotonous ocean of darkening yellows and browns.

Several hours later, puttering down gravel highways far from pavement and civilization, I checked my directions and began searching for an old church with a bent mailbox where I was to turn right and go exactly 1.43 miles to a weathered, red Massey Ferguson combine, then immediately bear south down a long driveway, past an auger cart (whatever that was), and park next to a large, gray Quonset hut. Excitement competed with doubt bubbling just below the surface even though the house would become my temporary prairie home, with strangers who would adopt me on the spot and never let go.

It was constant. Every minute of that first morning, there were birds in the sky: ducks flying, Canada geese honking, snows barking. Even more endless than the wheat and the horizon were the birds. But how could I possibly begin to fool that many with the four dozen decoys I’d brought?

Thankfully, my host, Bob, was a born-and-bred man of the prairie, a French-Canadian farmer most comfortable behind the wheel of a combine or fixing machinery. He called himself a “jack of all trades, master of none,” though he seemed masterful to me. His farm was organized, his crops flourished, he could repair anything, and he even made his own wine. As if the story couldn’t get any better, in his spare time he was a waterfowler.

Bob offered vague instructions to get to a big slough, involving a mile here and a mile there, following an old wagon rut, and even a cattle rubbing post. After getting miserably lost on that dark, two-mile journey, I arrived at the water’s edge and was greeted by the quacks, honks, and murmurs of thousands of roosting ducks and geese.

I fumbled around that first morning, resetting decoys three times, chasing birds instead of being where they wanted to be. It was much harder than I expected, and I only managed two ducks—a gadwall and a shoveler. Ruby sort of fetched them, but played with them more than anything, and it didn’t feel like her first real retrieves. Appreciative though dejected, I pulled into the yard and found Bob hunched under the hood of an old ’77 Chevy pickup. Looking down and talking as he worked, he met my description of the morning hunt with enough uh-huhs and mm-hmms that I could tell he wasn’t the least bit surprised.

Slamming the hood and wiping his hands on an old rag hanging from his back pocket, he said, “Sonny, you and I are going duck hunting tomorrow. I’ll even let you bring your dog.”

I couldn’t decide if his remarks were condescending or hopeful. I chose hopeful, although it was clear what he thought of my duck hunting and dog-training skills.

The next morning we hunted on a pothole small enough that I could have tossed a football to the other side. He dusted off a dozen old G&H Canada goose shells from a storage silo and positioned them in the surrounding stubble, instructing me to place only six mallards in the water behind us.

My skepticism disappeared in about an hour, after waves of mallards and pintails tried getting in. I became a believer. It was the controlled hunt that Ruby needed, and Bob was as effective with his old Model 12 pump as he was with a crescent wrench. For the next five days, he showed me where the dabbling ducks hung out, how to place my modest decoy setup for maximum effect, and to be patient, waiting to pull the trigger until birds left the roost. He taught me how to “back shoot” snow geese heading to water and how to park the truck to flare them our way.

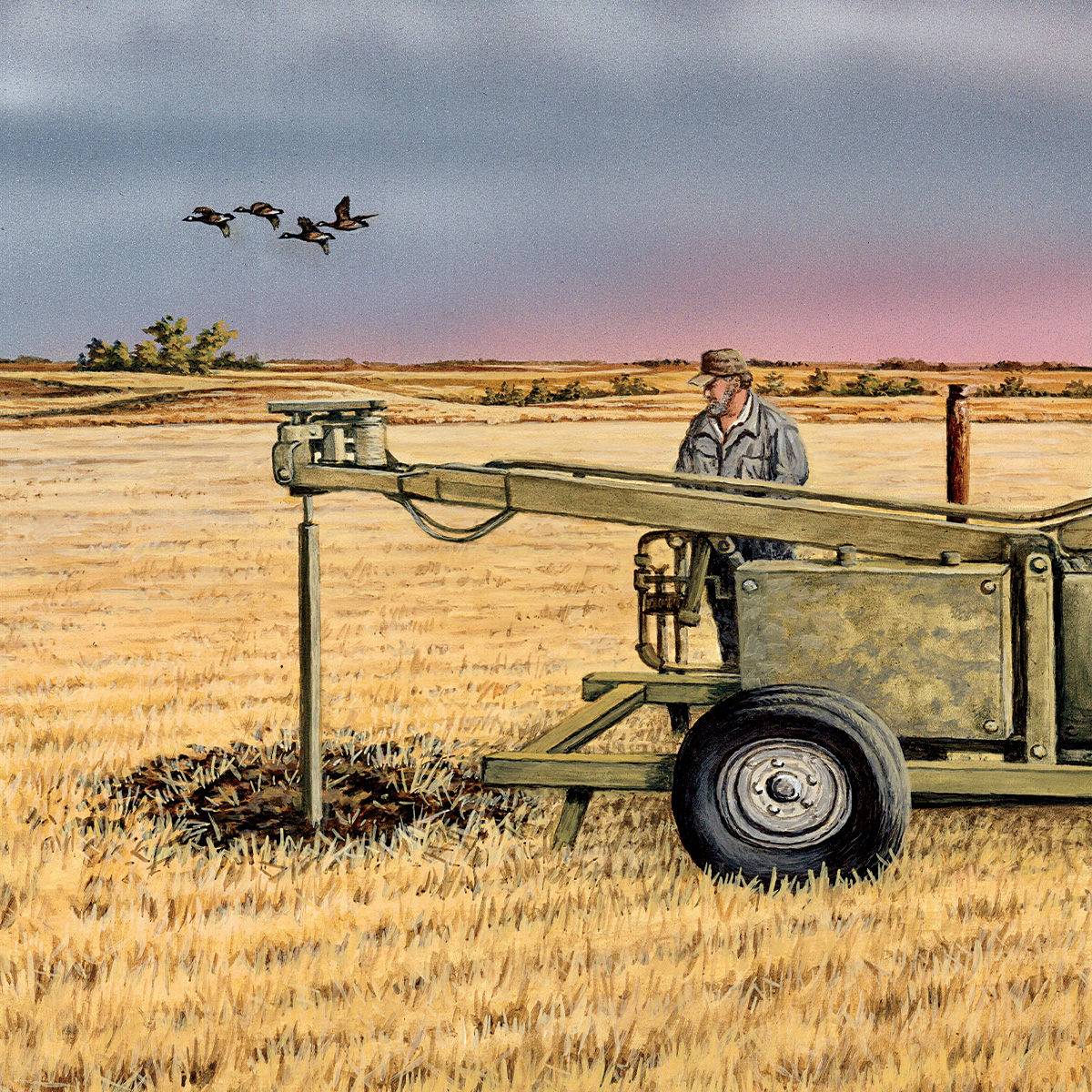

He introduced me to hunting ducks in fields, and while I prefer water, the way Bob did it made sense. He had built his own hydraulic pit digger so he didn’t have to lie down on the cold prairie. He named the contraption “Mother Goose,” and operating it required “a shot of scotch every time I bring up a load of dirt.” My job was to pour the scotch.

He showed me how to use a torch to singe the hair-like feathers from a plucked duck. One of the days it rained, and my tires became laden with prairie muck, leaving me with a miserable walk to the closest farmhouse to call for help. His advice was to stay off that road the next time it rained.

All the while, Ruby was there, watching, retrieving, and learning, and maybe that’s why she did so well. I was preoccupied with soaking up every piece of advice from this veteran of the prairie potholes, someone so different in voice and appearance from my own dad but strangely familiar when it came to patience for teaching and excitement for the sport. Rubes was learning the same way I was—by observing.

The last morning, Bob could sense that I was ready to go it alone, back to the place I’d hunted that first day, which felt like a month ago. But this time I went armed with a knowledge of prairie ducks and a retriever who’d fetched more birds in a week than she’d get in two seasons back home.

Borrowing a leaky old johnboat, I stealthily put decoys out in the dark from my knees so I could enjoy the roosting geese without alarming them. I clipped a pair of snows from the last flight to depart for their morning feed, then waited for mallards that parachuted down from the blue-sky heavens to my little cattail hangout in the far corner of the marsh; a meager spread of decoys is more than enough when you’re in the right spot. I felt the grief for Maggie dissipate as my pup became a retriever, and I knew she’d be the one I’d compare all others to.

With the truck pointed east and packed to the gills, not to mention a Canadian lunch that would take 50 miles to finish, we said our good-byes only after promising to return next year. Ruby was already stretched out and snoring, feeling like an old pro though she wasn’t even 10 months old.

Picking my way toward the border, I tried to discern the best part of the trip. Was it the drive or the remoteness? Maybe it was that I proved to myself that I could do it, or maybe it was seeing that many birds. Perhaps meeting my new adoptive family, or the bond that was forming between hunter and dog.

Settling in for the miles ahead, the answer was clear.

It was everything.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy