Strategies for Small-Water Ducks

Whether up north or down south, the smallest wetlands can offer some of the best hunting opportunities for dabblers

Whether up north or down south, the smallest wetlands can offer some of the best hunting opportunities for dabblers

By Brad Fitzpatrick

They say that good things come in small packages, but I was a bit surprised when our guide led us to a postage stamp-sized impoundment surrounded by agricultural fields and pastures during early teal season. We were hunting along the Texas Gulf Coast last September, just a few weeks after Hurricane Harvey had brought record rainfall to the region, and the floodwaters still hadn't completely receded. With so much water all around us, I couldn't help but wonder how attractive this meager pond would be to the flocks of blue-winged teal pouring into the area.

Any doubts that I had about our spot quickly vanished when, not long after legal shooting light, the unmistakable sound of whistling wings announced the arrival of the first flock of the day. We dropped a few birds from that bunch, but that was just a primer. Soon flock after flock of teal came diving and twisting into our little oasis. Just as fast as we would fire at one group, another would zip in over our small decoy spread, leaving us barely enough time to reload our shotguns. We got our limits quickly, and as we packed our gear and started for the truck, I looked back at that pond in disbelief. It seemed extraordinary that such a small piece of water could be so alluring to ducks.

I shared that story with two Ducks Unlimited staffers who are avid small-water hunting enthusiasts, and neither was surprised by our success. Dr. Scott Stephens and Chad Manlove are both veteran waterfowlers who understand that in some cases the smallest, most overlooked waters produce the biggest hunting rewards. Here's their advice on how to scout and hunt these hidden honey holes in vastly different parts of the country, early and late in the season.

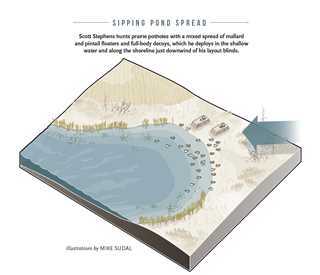

Stephens, who is director of regional operations in DU Canada's Prairie Region, hunts both dabbling and diving ducks on the prairie potholes of Canada and the Dakotas. In early fall, when he's specifically targeting dabblers, he avoids the larger wetlands that the birds roost on at night. Instead, he seeks out day roosts or "sipping ponds," as he calls them, pursuing ducks that drop in to quench their thirst and rest as they fly to and from nearby grainfields.

"My experience is that field-feeding ducks tend to stop at these sipping ponds to drink and loaf," Stephens says. "It's not entirely clear to me why ducks prefer this small water over night roosts, but it may be that after feeding on dry wheat, barley, or oats, the birds are thirsty and looking for a little water to aid in the digestion process for a big crop full of grain. Some of these wetlands may also offer moist-soil plant seeds and submersed aquatic vegetation that provide essential nutrients that the birds can't get from feeding only on waste grain."

These sipping ponds are frequently quite small-just an acre or two in size-and they're often overlooked by hunters focused on bigger water. This can be a boon for freelance hunters willing to seek out these places. "These day roosts are usually pretty easy to find if you know what to look for," Stephens explains. "When you're scouting ducks that are feeding in a field, watch for small bunches getting up and disappearing-without circling-into these small depressions. At times, the whole pond can be covered in ducks."

If you find one of these ponds after the birds have departed, there will be other telltale signs that you've discovered a potential hunting hot spot. "The place will be covered in feathers and there will be duck tracks along the bank and in other shallow areas where the birds stand. If you're setting up before dawn for a morning hunt, the best indication that you've located a day roost is that you'll find no birds roosting on it overnight," Stephens says.

A good way to locate these areas is by following the birds after a successful morning hunt. "If you reach your bag limit early, get out and follow the ducks when they leave fields in which they are feeding," Stephens says. "You can also follow the birds in the early afternoon to see where they are roosting during the day before the evening feed. Ducks use these areas throughout the day, but often only use night roosts before and after shooting hours. That's another big advantage for hunters."

Stephens says that these small potholes can remain productive well into the season, as new birds arrive from the north. When these diminutive wetlands freeze up, however, the ducks that remain on the prairies will often move to larger waters, which remain open later in the season.

Unlike night roosts, many of these midday loafing ponds will have little or no emergent vegetation. This is good for the birds, because it allows them to better see approaching predators. But it can be bad for hunters, as it provides little cover to hide in. To stay off the ducks' radar, Stephens recommends that you use layout blinds covered with local vegetation and wear full camouflage, including a facemask or face paint. "If the birds see anything out of place, they're likely to fly off to another pond, and there are plenty to choose from on the prairie landscape," he says.

While you may have to hike some distance to hunt a hard-to-reach pothole, you won't need to haul in dozens of decoys. A maximum of two dozen will usually suffice. "A few floaters in the water and a few full-body decoys along any bare banks will look completely natural and sell the whole setup," Stephens says.

In keeping with this minimalist approach, Stephens calls sparingly when hunting small waters. "If the ducks want to be there, they will just drop in. You don't have to call much, if at all. The ducks are coming, so let them come," he says.

Chad Manlove is DU's managing director of development for the Southern Region, whose conservation programs he supervised for several years while working as a biologist. He hunts primarily in the Mississippi Delta, where secluded ponds and sloughs are particularly attractive to wintering ducks. "In the Deep South, small-water hunting can be very effective late in the season, when ducks tend to be paired up," he says. "Paired birds prefer secluded pockets of water, where they can feed and rest undisturbed. The birds usually start pairing up in late December."

Scouting is essential to locating the best of these small waters, especially when you're hunting on public land, where competition can be stiff. "The birds experience a lot of pressure late in the season," Manlove explains. "You have to be willing to put in the effort to find places that are off the beaten path. At the same time, I never hunt small water without watching the birds for one or two days. I want to make sure the ducks are using these areas on a regular basis."

Finding where to hunt is one thing, but deciding when is something else. Manlove says that in the Mississippi Delta, many small-water areas produce the best results on clear days when there's a north wind blowing at five to 10 miles per hour. "Go when the weather offers the best potential for success," he advises. "Don't pick a random day when the weather is not ideal, or you'll burn out your spot with marginal results."

He adds that it's easy to overhunt these small bodies of water. "Too much pressure can spoil a great area. For that reason, you need to hunt these honey holes sparingly." A good rule of thumb is to shoot these spots only once a week. If you manage pressure, these areas can remain productive for several weeks.

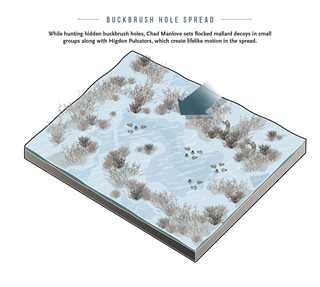

Staying hidden from the prying eyes of late-season ducks is a key to success on small waters. Fortunately, many of these areas provide an abundance of natural cover. "Willow patches and buckbrush thickets offer great concealment-so use it to your advantage," Manlove says. "By the same token, a portable dog blind is a must for keeping your retriever comfortable and hidden from sight."

Few decoys are needed in the close confines of sloughs, timber holes, and small ponds. Depending on the size of the hole, you can get away with setting out just six to 12 decoys. For added realism, Manlove recommends using only your best-looking decoys. "Flocked mallard decoys work well in this situation," he says. "And motion adds realism too. Old-school jerk strings are still very effective on small water. I also use a few Higdon Pulsator decoys to make my small spread look like an active group of ducks."

Manlove suggests leaving powerful magnum loads at home and going with lighter cartridges when hunting these small waters. He shoots 3-inch Hevi-Metal loads of size 6 shot. These lighter, faster duck loads provide plenty of knockdown power on close-range birds. You'll also want to use a more open choke, such as improved-cylinder, for the best pellet coverage at short distances. Small-water hunting also gives you the perfect opportunity to take a light-kicking 20-gauge to the marsh.

As for calling, Manlove recommends toning it down on the wintering grounds. "The birds can be extremely call-shy by the end of December," he says. "I sometimes use a five-note greeting call, a few soft quacks, or some feeding chatter just to let the working ducks know I'm there. Other times, I'll use a lonesome hen call to entice unpaired drake mallards. But on calm mornings with little wind, I'll leave the call hanging on my lanyard and let the decoys do the work."

SCOUTING SMALL-WATER HABITATS

Locating small, out-of-the-way wetlands frequently requires sitting down with an aerial map and identifying any speck of blue you see as a potential hunting spot. Some of these hidden waters are so tiny, however, that they may not even show up on a map. The only way to find these areas is to get out and scout. Drive the backcountry, looking for flocks of birds rising or settling down into hidden wetlands nestled in agricultural fields and along rivers and marshes. Check for feathers and tracks in and around sloughs and small ponds, paying special attention to those located near grainfields. Take the time as well to look for evidence that other hunters are using the pond. If you see footprints, worn paths, empty shotshells, blind materials, and other signs of recent hunting activity, you may want to look elsewhere for an untrammeled hunting location.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy