Five Perfect Setups

You can't miss with these deadly decoy spreads designed for classic waterfowl habitats

You can't miss with these deadly decoy spreads designed for classic waterfowl habitats

Arriving to find the pond half frozen, I repurpose a few goose floaters, placing them in the snow along the edge of the ice, before putting the others in the open water nearby. Then I set the duck decoys closer, in a classic J pattern, with the shank running straight downwind. Finally, I hide my layout blind in the tall grass and snow along the shoreline.

For about an hour, passing flocks of waterfowl ignore my setup. Then, as the sun climbs above the trees behind me, illuminating the decoys, every bird I see makes a beeline for my spread. A gadwall lands on the water, then a goldeneye, a pair of Canada geese, a flock of mallards, and, finally, a single greenhead finish in quick succession, offering easy shots. I call it a day, one duck and one goose short of full limits. I laugh to think that I have shot a perfect seven for seven, including an almost-on-purpose Scotch double on the geese, which makes up for my one shot in the air to flush the gadwall—my only “miss” of the morning.

When you have found the right place at the right time and you’re sufficiently hidden, a well-positioned decoy rig puts the finishing touches (pun intended) on a perfect day. While there is no such thing as a perfect spread for all situations, the following experts have devised decoy setups that consistently deliver birds in specific types of habitats and conditions. If you hunt in similar places, they just might work for you too.

Professional upland bird and fishing guide Christi Holmes enjoys hunting ducks on her days off. Based in Machias, Maine, she has access to numerous beaver ponds not far from the coast. Her favorite time to hunt these small, secluded waters is early in the season, when the temperatures are mild and there are still lots of wood ducks around as well as American black ducks and mallards.

Maine’s numerous beaver ponds, swamps, and tidal marshes provide an abundance of habitat for waterfowl. “All that water can be too much of a good thing because the ducks have so many options,” Holmes says. “Since Maine doesn’t allow Sunday hunting, it’s a good day to spend scouting.”

Holmes looks for small concentrations of ducks loafing on beaver ponds near blueberry fields where the birds feed. Once she finds a spot that’s holding ducks, she checks the local tide tables. “We have huge tidal swings here—as much as 12 feet,” Holmes explains. “The perfect time to hunt beaver ponds is when the tides go out at first light, forcing the birds to come inland early.”

Since many of the ponds she hunts are a fair distance from the nearest logging road, she uses a small spread of only 12 to 18 oversized decoys, consisting of mallards, black ducks, and wood ducks. When deploying her spread, Holmes leaves one mallard hen or black duck near her hiding spot to appear to be the source of her calls, and then she sets the remaining decoys in scattered pairs around the edges of the pond.

The ponds that Holmes hunts are often less than 50 yards wide, and in a crosswind, she sets pairs of mallards and black ducks upwind of her position to steer approaching birds directly in front of her. She places her wood duck decoys in a group along the shoreline on the other side of the pond.

With the decoys set, Holmes makes a temporary blind out of natural cover. “Concealment is very important when you are hunting beaver ponds,” she advises. “Black ducks are wary, so you have to tuck in well and not trample the cover.”

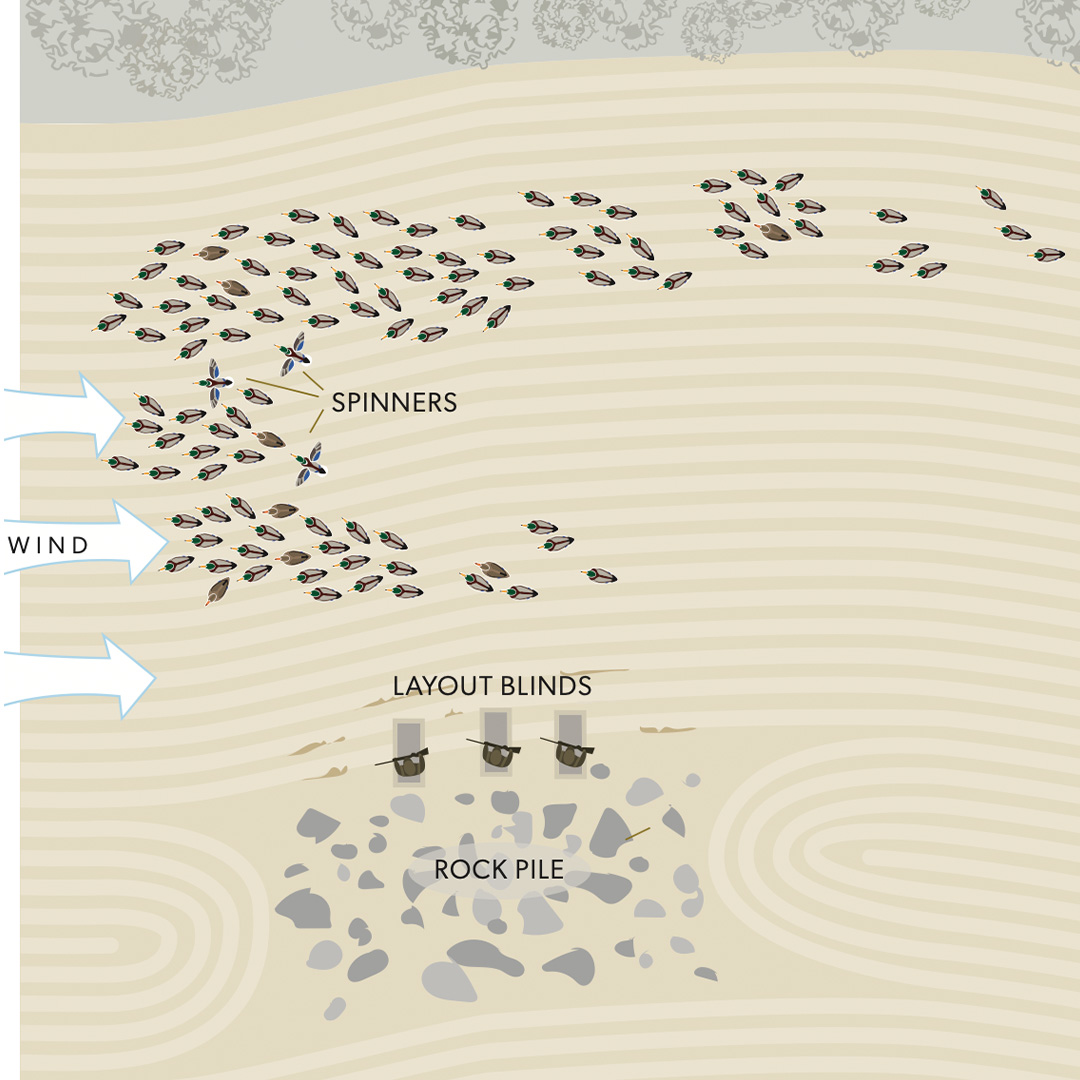

Joe Fladeland cut his teeth hunting ducks on harvested grainfields in North Dakota, where clouds of mallards, pintails, and other dabblers gather to feed in the fall. When he scouts, he looks for two things: ducks and rock piles. “It’s hard to hide in cut wheat or peas,” says Fladeland, who guides for Dirty Bird Outfitters in Bismarck. “If we can find ducks feeding in a field with rock piles, we are going to have a good time.”

On the prairies, farmers gather rocks to clear fields for tilling, often building piles of stones 10 to 20 yards across. Fladeland says the rock piles make hiding hunters much easier than it is in fields without any structure. In fact, he prefers to place the backs of his layout blinds right against the rocks.

Fladeland sets his spread so decoying birds will cross in front of the shooters instead of coming straight into the blinds. He sets the decoys either in two lines or in a J-hook configuration. While many hunters use goose decoys while hunting ducks on the prairies, Fladeland prefers full-body duck decoys. “I like to match what I see,” he says, “and ducks and geese tend to feed separately, especially later in the season.”

As for decoy numbers, Fladeland has cut the size of his spread down to about 200 decoys. He places three to six spinning-wing decoys in the bend of the J, just upwind of the blinds. Fladeland may extend the trailing lines of decoys 100 or even 200 yards downwind of his position. “You usually don’t have to worry about ducks stopping short,” he says. “Ducks are greedy, and they want to jump to the front of the line. They will usually come up the string to the landing hole, where the spinners are.”

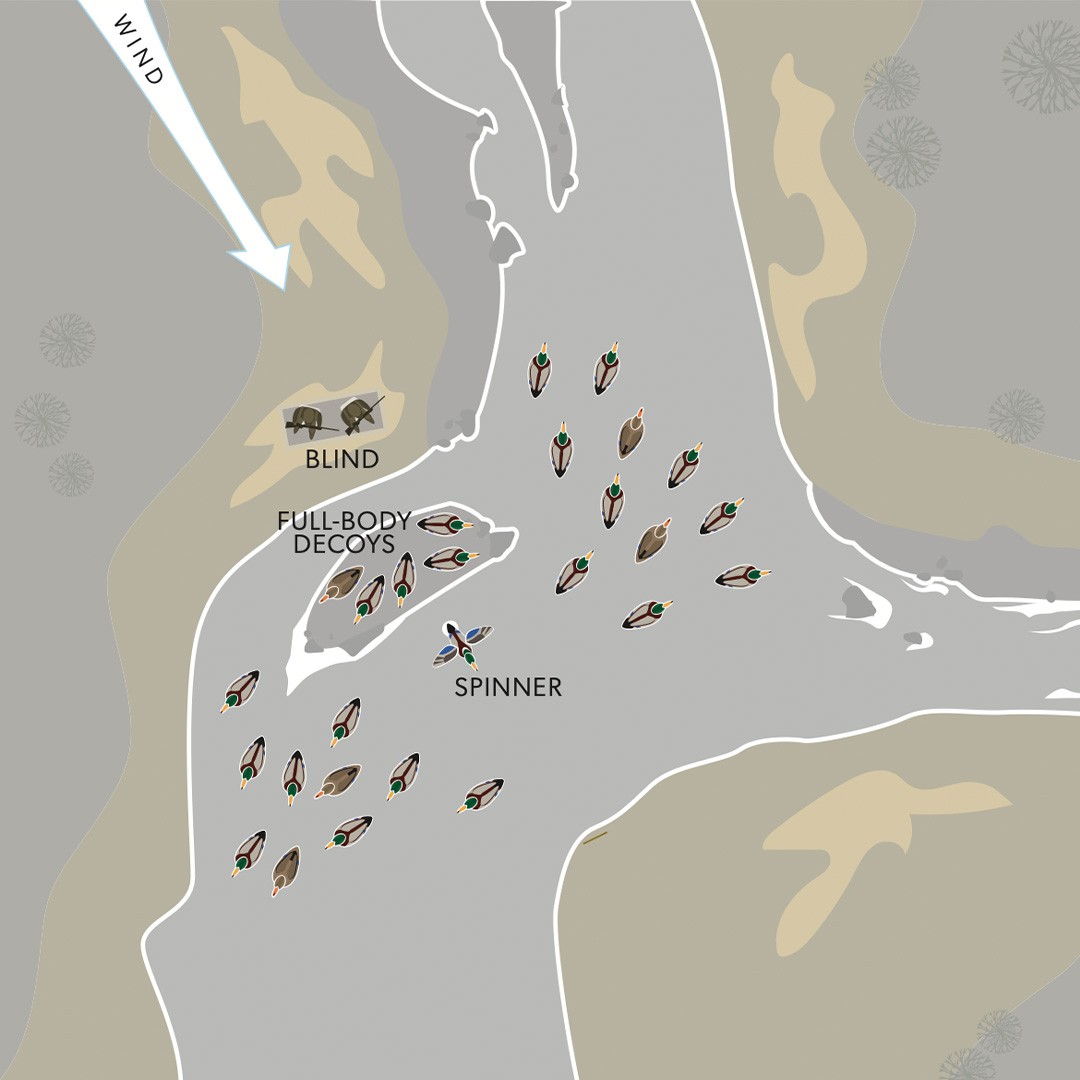

If you can find open water in cold climates, you will find ducks, sometimes a lot of them. Montana DU State Chair Bridger Pierce knows this as well as anyone. He hunts spring creeks in the western portion of the state, where the hunting heats up as the temperatures drop. “The warm- water creeks never freeze, even when the rivers do,” he says. “On very cold mornings, the steam rising off the water can make it hard to see at first light.”

When there is no other open water around, mallards use the creeks both for roosting and for loafing after feeding in the surrounding grainfields. Pierce scouts for concentrations of birds and then sets up to ambush them when they return from the fields. He arranges his decoys to look like a relaxed group of loafing ducks. “One of my favorite spots has a small island in front of the blind,” he explains, “and we set a few full-body decoys on it because mallards love to rest there when they are in the area.”

Pierce says two to three dozen mallard decoys will usually suffice for hunting smaller spring creeks. He deploys his decoys in two groups with an open landing hole between them and a spinning-wing decoy in the center of the hole to square up decoying flocks. In very cold, windy weather, Pierce sets the decoys closer to the bank to look like birds hunkered down in the lee.

Pierce’s favorite hunting conditions are bitter-cold, blustery days when the wind forces the ducks to fly low along the creek channel. “If ducks are feeding close by, we’ll get shooting at first light. Otherwise, ducks trickle back later in the morning in pairs and small groups,” he says. The wait can be long on bitterly cold mornings. “We hunt out of box blinds and put heaters in them. When it’s 20 below, that makes it bearable until we have to go out and clean the snow off the decoys.”

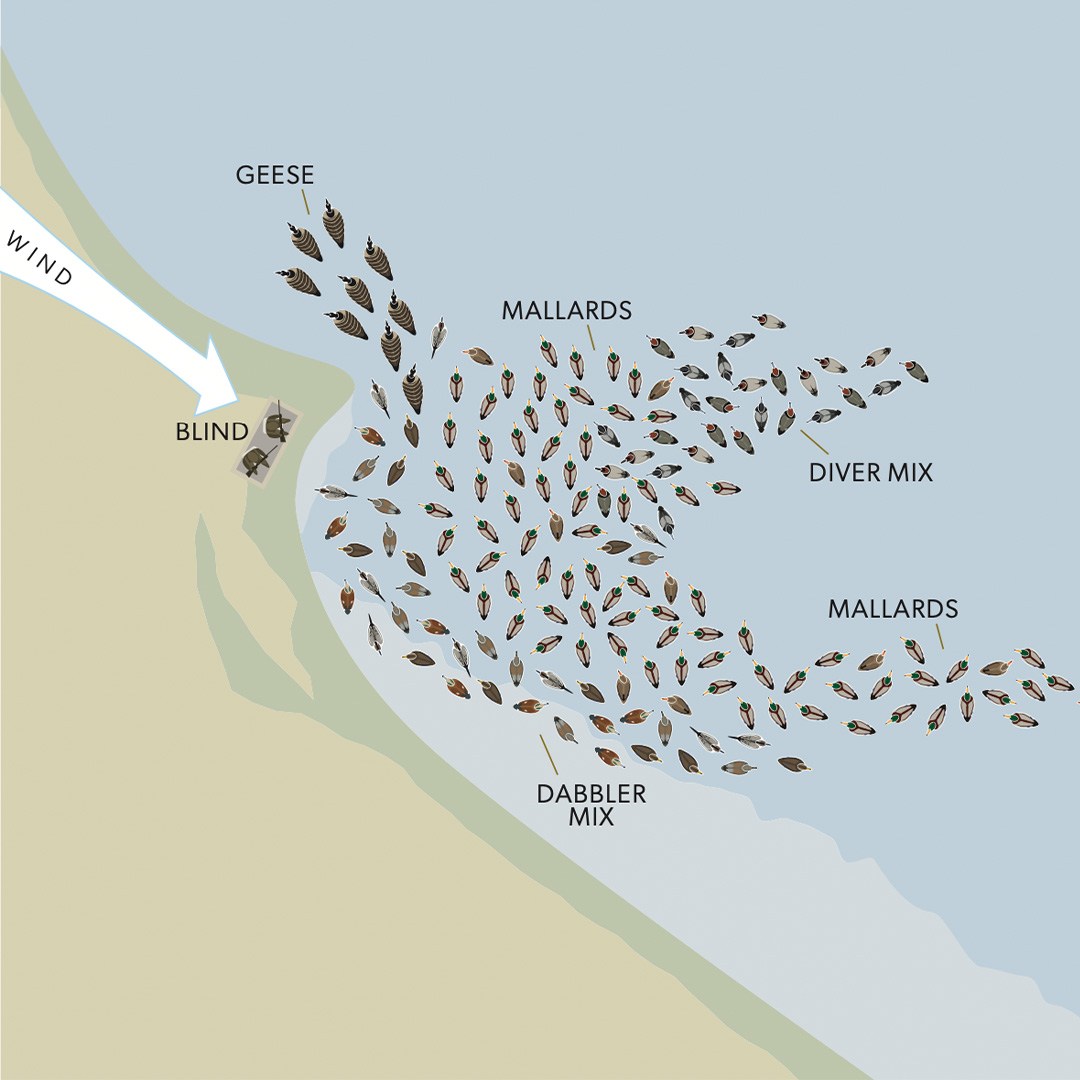

The perfect time to hunt a point in a marsh or a natural lake is on a windy “flight day” when new birds are arriving from the north. So says Jay Anglin, who has hunted ducks in the Great Lakes region for more years than he can count.

“If it’s a flight day, we’re going to go big in terms of decoy numbers,” Anglin says. “You know when you fly into Las Vegas and you can see the Strip out the window? I want ducks that are way up high to look down, see our spread, and think I need to go down there.”

“Big” in Anglin’s case means 150 to 200 decoys, and he either teams up with friends who bring their own boats or tows a smaller boat full of decoys behind him. Anglin prefers to set his rig off a prominent point where the decoys will be as visible as possible. Within that spread, he likes variety. “I use mainly mallard decoys and mix in some wigeon, pintails, and fully flocked black ducks to give the spread some pop. I also include some gadwall decoys because gadwalls work better to their own species,” he says. He also includes a separate group of divers, consisting of an equal mix of drake canvasbacks, redheads, and bluebills.

Anglin deploys his decoys in a loose J configuration with the bulk of the puddle duck decoys placed in the calm water on the downwind side of the point. He places most of the divers outside the main body of puddle ducks on the upwind side of the spread. Although it’s a big spread, his primary objective is to get birds in as close as possible. “On windy days especially, you need lots of duck decoys to get ducks really close,” Anglin says. “A duck at 25 yards looks like a perfectly finished bird, but by the time you stand up to shoot on a windy day, it’s a 40-yard shot or longer. I want them in tight where I can see their eyes.”

As a final touch, Anglin puts a group of magnum Canada goose decoys on the upwind side of the point. If he is short on space in the boat, he leaves the goose decoys at home and relies on the call. “You can bring in singles and pairs of geese to a duck setup,” he says. “It’s like turkey hunting without decoys. As geese are coming in, you can see them looking for the source of the call.”

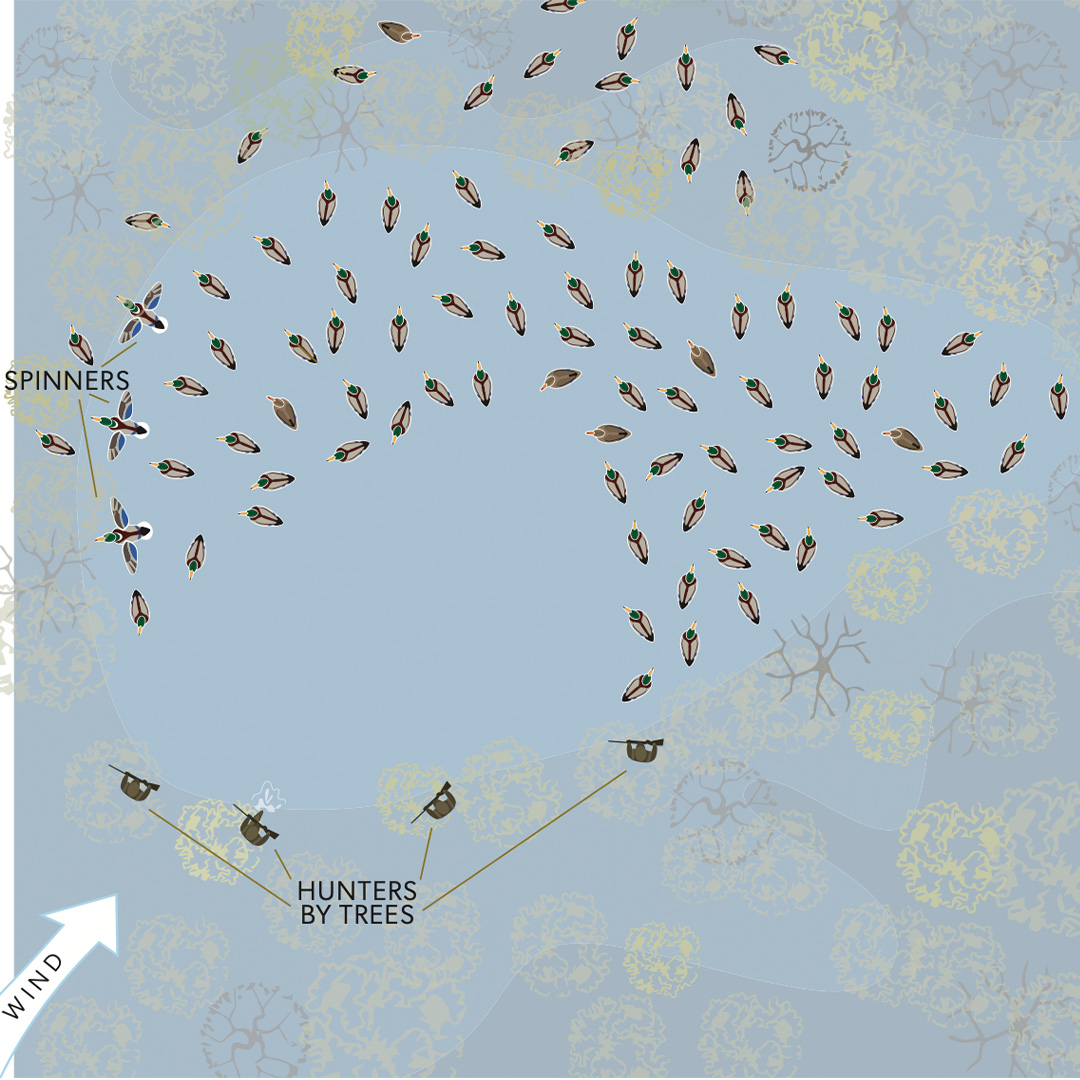

Rusty Creasey grew up around the famed Coca Cola Woods near McCrory, Arkansas. His late uncle, Harvey Shue, managed the club for 40 years. Creasey took over as manager in 2004 and guides hunters on the club’s 640 acres, which includes 520 acres of classic flooded green timber. While the hunting in eastern Arkansas typically improves as cold weather pushes ducks down from the Midwest, Coca Cola Woods holds ducks all season, from November through the end of January. “We cooperate with our neighbors to provide habitat early, and after that first good push around Halloween, we keep those birds for all 60 days of the season,” Creasey says.

With a limited number of timber holes on the property, Creasey believes in picking up his spread after every hunt. “We used to leave our decoys out all season, but we have learned that we’ll have better success if we only set up in the holes that we hunt that morning and then pick up when we are through hunting,” Creasey explains. “That may not matter with flight ducks, but it makes a difference when you’re holding the same birds in the area. You don’t want them to see the same thing every day.”

Creasey typically uses about six dozen mallard decoys with flocked heads, which he believes look more realistic to close-working ducks. He places his spread in an open V formation, leaving plenty of room for birds to finish. He runs three spinning-wing decoys on the upwind edge of the hole but is quick to turn them off if ducks show any signs of spooking.

As the season wears on and the birds become more decoy shy, Creasey will put some or all the decoys in the woods around the hole to appear like ducks that have landed and moved back into the surrounding flooded woods to feed and rest. On rare occasions, he’ll use no decoys at all, and simply call and kick water to attract ducks. “Last January we hunted a small hole that was created by a blowdown in the woods,” Creasey says. “The first two groups started climbing as soon as they saw the decoys. Maybe it was the shine or maybe it was just ducks being ducks, but I picked up the decoys, called, and kicked water, and the next group came right in. We killed ducks for a solid week that way.”

Regardless of what decoy spread he uses, Creasey’s goal is always to get ducks in as close as possible. “Ducks in the woods will come down into the hole and flutter around. You don’t have to shoot them right away, and I can often pump them with the call to get them closer to the guns,” he says. “I want ducks at 15 yards, four feet off the water when I call the shot.”

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy