Will the Ducks Bounce Back?

History has repeatedly shown that waterfowl populations rebound when wet weather returns to the prairies

History has repeatedly shown that waterfowl populations rebound when wet weather returns to the prairies

From the Ducks Unlimited magazine Archives

By Richard M. Kaminski, PhD, Michael G. Brasher, PhD, and Nicholas M. Masto

If you’re like some of us who have been around since the 1950s, you might remember the 10-cent paddle ball toy made by the Fli-Back Company of High Point, North Carolina. The company thrived during the 1950s making paddle balls, yo-yos, and other playthings. Annual surveys of waterfowl breeding populations and habitat conditions also were launched during the 1950s. These surveys were conducted without interruption from 1955 through 2019, when the COVID-19 pandemic led to temporary suspension of the surveys.

Like the rubber ball attached to a Fli-Back paddle, duck populations bounce up and down over time. Waterfowl managers have learned from decades of scientific study that the size of duck populations is linked to wetland conditions on the birds’ breeding grounds. Nowhere is this relationship more profound than in the Prairie Pothole Region of the United States and Canada. While historical wetland drainage and other landscape conversions have reduced the total number of prairie potholes, precipitation continues to drive how many wetland basins hold water and are available to breeding ducks each spring. Periods of drought lead to predictable drying of wetlands, and duck populations subsequently decline as birds lose access to highly productive pairing and brood-rearing habitats on the prairies.

After many years of generally favorable wetland conditions on the prairies, widespread drought returned to the pothole country during the summer of 2021 at a scale and severity that had not been witnessed since the 1980s. Based on those conditions, waterfowl biologists believe that some duck populations declined. If the prairie drought persists in 2022 and possibly longer, what might the future hold for ducks and their habitats? Let’s take a look back at past patterns of wet and dry cycles and their effects on breeding duck populations on the prairies.

Waterfowl populations were relatively high when annual waterfowl and wetland surveys began in the mid-1950s, but duck numbers trended downward in subsequent years as drought intensified on the prairies. They remained at low levels throughout most of the 1960s, and daily bag limits and season lengths in the United States were reduced accordingly.

Wetland conditions and duck populations rebounded during the 1970s. The senior author of this article, however, vividly recalls a very dry spring in 1977 while conducting his doctoral research on breeding ducks and aquatic invertebrates on Manitoba’s Delta Marsh. That year was so dry that DU Canada, the Delta Waterfowl and Wetlands Research Station, and the Province of Manitoba partnered to finance construction of a dike around the drought-stricken study area to hold water artificially pumped from the marsh. Pond numbers increased the following spring and reached record levels in 1979, when catastrophic flooding occurred in the Red River Basin from Grand Forks, North Dakota, to Winnipeg, Manitoba.

The 1980s brought the return of severe drought on the prairies, which was reminiscent of the Dirty ’30s. Over a period of successive years, breeding duck populations plummeted to record lows similar to those of the early 1960s. Many waterfowl community members wondered if duck populations would ever rebound from the protracted drought of the 1980s, especially given concurrent losses of grasslands and wetlands across the prairies. In addition to the near-term consequences for ducks and agriculture, drought encourages disking, drainage, and other modifications of wetlands, especially the shallow basins so important to breeding mallards, northern pintails, and other ducks. The effects of these modifications often persist even after wet weather returns, reducing the potential productivity of prairie landscapes for waterfowl and other wildlife. Thankfully, continental conservation efforts launched during the 1980s have helped slow habitat losses on the prairies and continue to make progress (see sidebar).

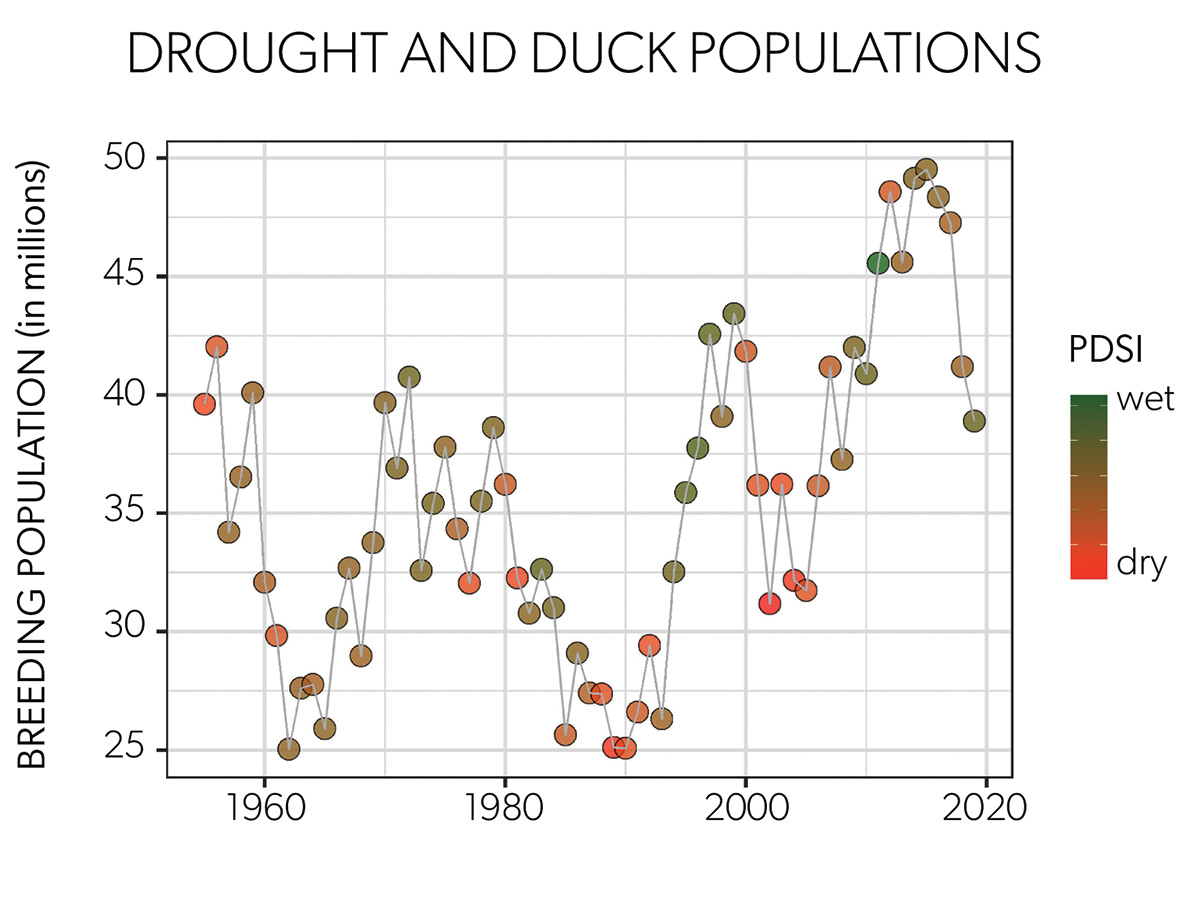

The relationships between precipitation, wetlands, and breeding duck populations can be illustrated using the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), which provides a relative measure of soil moisture and surface water conditions. On the graph above, data on total duck population size and PDSI from the US Prairie Pothole Region from 1955 to 2019 show declining and depressed duck populations associated with years of severe drought (shown in orange and red). Years of intermediate wetland conditions (brown) typify transitional years, while wet conditions (green) correspond with increasing and abundant duck populations.

As in the 1960s, persistent drought during the 1980s and early 1990s brought restrictive season lengths and daily bag limits, which were reduced to 30 days and three ducks in the Mississippi and Atlantic Flyways from 1988 to 1993.Duck populations remained at low levels until 1994, when abundant precipitation recharged wetlands across the prairies.

Duck populations soared to record highs during a series of wet years in the mid- to late 1990s, and with them came the return of liberal hunting regulations under a new regulatory framework: Adaptive Harvest Management (AHM). These wet years were like the Fli-Back ball hitting the paddle. The rebound in duck numbers was amplified by abundant wetlands embedded within restored grasslands, which provided highly productive habitat for prairie-nesting ducks and other birds.

The dawn of the 21st century brought a return to cyclical drought, and duck numbers again declined during the early to mid-2000s. Departing from the harvest management practices of the past, however, liberal hunting seasons and bag limits remained in place, reflecting advancements in our understanding of the resilience of waterfowl populations and sustainability of scientifically informed harvest regulations via AHM. Dry to intermediate wetland conditions prevailed throughout much of the decade, and duck populations again turned downward. However, those numbers remained well above the lows of the late 1980s and early 1990s, likely buoyed by continued habitat conservation.

With the return of wet weather and abundant ponds in 2010, duck populations made an impressive comeback, soaring to a record high in 2015 and remaining at high levels through 2019 despite ongoing conversion of wetlands and grasslands across the prairies. However, northern pintails and scaup have remained below their long-term averages, providing evidence of the long-term impacts of habitat loss and the need for continued landscape conservation.

As you know, severe drought returned to the prairies and much of the western United States and Canada in 2021, but increased snowfall over the past winter in eastern portions of the Prairie Pothole Region may bode well for breeding ducks this spring. Let’s hope more precipitation falls across North America’s prairies in time to benefit returning waterfowl this spring.

Like the elastic band that connects the rubber ball to the paddle, waterfowl habitats protected and managed by Ducks Unlimited and its partners will help draw ducks back to the breeding grounds when wetland conditions improve. Consequently, we should remain positive. History has shown us that the ducks will bounce back when water returns to the prairies.

Habitat on the Ground, Ducks in the Air: When breeding duck populations plummeted to historic lows during the mid-1980s, the conservation community took decisive action by implementing two of the most successful waterfowl habitat conservation efforts ever conceived. The Conservation Title of the 1985 Farm Bill mobilized billions of dollars to protect and restore vital grasslands and wetlands across the US portion of the Prairie Pothole Region, largely through the Conservation Reserve Program. One year later, the North American Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP) was enacted, and it would become the world’s finest example of an ecosystems management partnership. Without the US Farm Bill, NAWMP, and their conservation initiatives, partnerships, and funding, we might yet wonder if the ducks will be able to bounce back when improved wetland conditions return to the prairies.

Dr. Richard M. Kaminski is the retired director of the James C. Kennedy Waterfowl and Wetlands Conservation Center at Clemson University, who resides in Pawleys Island, South Carolina. Dr. Mike Brasher is DU’s waterfowl scientist based at its national headquarters in Memphis, Tennessee. Nicholas M. Masto is a PhD student and 2022 DU Fellowship recipient at Tennessee Tech University.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy