Understanding Waterfowl: Waterfowl of Mexico

This country's diverse wetlands provide crucial wintering habitat for many of North America's ducks and geese

This country's diverse wetlands provide crucial wintering habitat for many of North America's ducks and geese

By Eduardo Carrera and Scott C. Yaich, Ph.D.

Long after we have stowed away our decoys for another year, waterfowl still have months of winter ahead of them before they can head north to their nesting grounds. If you are a regular reader of this magazine, you are probably already aware of the importance of key waterfowl wintering habitats in the United States, such as seasonally flooded bottomland hardwood forests in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley, the coastal marshes of Louisiana and Texas, and flooded rice fields in California's Central Valley. But you might be surprised to learn that many of the ducks and geese that pass over your blind in the fall actually spend the winter much farther south, on wetlands in Mexico.

Mexico encompasses about 9 percent of the North American mainland, but an estimated 20 percent of the continent's waterfowl winter here. This includes 85 percent of Pacific brant, 35 percent of redheads, 20 percent of northern pintails, 15 percent of northern shovelers, and 10 percent of American green-winged teal. Blue-winged teal most often come to mind in connection with Mexico, and over 80 percent of this species' population either winters in or passes through the country while en route to even more southerly destinations. In total, some 35 species of waterfowl occur in Mexico, either as seasonal visitors or permanent residents.

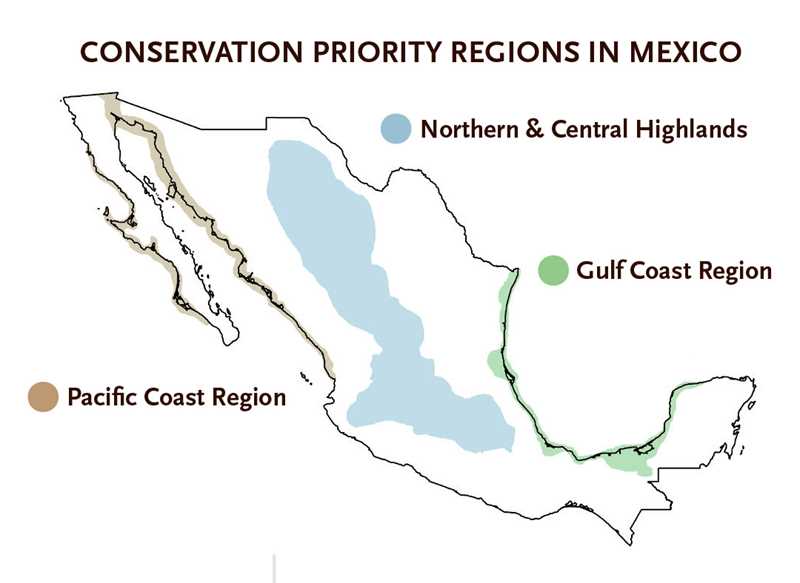

Ongoing wetland inventory work by Ducks Unlimited de Mexico (DUMAC) has documented that the country has more than 24 million acres of wetlands. Of these, about 43 percent are inland freshwater wetlands and the rest are brackish and saline wetlands along Mexico's rich and expansive coastlines. Biologists have identified 28 wetland systems that encompass the country's highest-priority habitats for wintering waterfowl. These wetlands are as diverse as the regions in which they are located.

Encompassing 14 high-priority wetland systems, Mexico's Pacific Coast hosts about 38 percent of the country's wintering waterfowl. Along the west coast of the Baja Peninsula, a number of nearly pristine lagoons support rich beds of eelgrass, a submersed aquatic plant that is a vital food source for Pacific brant. These shallow bays, as well as similar estuaries on the mainland coast, are North America's most important wintering grounds for these birds. In the Baja's arid interior, increasing demand for limited water supplies has resulted in a nearly total loss of its temporary wetlands. This makes protecting the region's coastal lagoons all the more important.

Mexico's mainland west coast is more ecologically diverse. Key waterfowl habitats in this region include coastal lagoons and mangrove wetlands as well as inland freshwater emergent wetlands. Large man-made reservoirs supplement the region's natural wetlands. The three coastal states of Sonora, Sinaloa, and Nayarit provide significant migration and wintering habitat for Pacific Flyway waterfowl. Anecdotal observations indicate that during the recent California drought, these states hosted unusually large numbers of wintering pintails and other ducks. This apparent redistribution of drought-displaced waterfowl from California underscores the importance of this region's wetlands to continental waterfowl populations. In addition to pintails and brant, large numbers of migrating and wintering American wigeon, shovelers, scaup, and redheads as well as green-winged, blue-winged, and cinnamon teal are supported by wetlands along Mexico's Pacific Coast.

Seven of Mexico's highest-priority wetland systems are found in the Gulf Coast region, which supports 35 percent of the country's wintering waterfowl. This region, which stretches from the dry Rio Grande River basin to the semitropical Yucatán Peninsula, is extremely diverse. At the northern end of the region is the Laguna Madre, which Mexico shares with Texas. This ecosystem, one of DU's highest continental priorities, supports more than 70 percent of the continent's redheads and large numbers of scaup. These diving ducks feed extensively on shoalgrass, which flourishes in the Laguna Madre's hypersaline waters, and then visit small wetlands on ranchlands along the coast, where the birds drink large quantities of freshwater each day to purge their bodies of excess salt loads consumed while feeding. These freshwater wetlands also provide important wintering habitat for blue-winged teal, pintails, lesser snow geese, and greater white-fronted geese.

To the south are extensive mangrove wetlands, which collectively form one of the most diverse, productive, and threatened ecosystems on the planet. About two-thirds of Mexico's mangroves are distributed along the Gulf and Yucatán coasts. Sadly, approximately 800,000 acres of these vital wetlands have been lost since the 1980s. Although mangrove losses along the west coast have primarily been caused by the explosive growth of shrimp farming, the primary threats to mangrove habitats along the Gulf Coast are tourism and other forms of development. Blue-winged teal and pintails are the waterfowl species most adversely affected by the ongoing loss of these highly productive wetlands.

Home to seven high-priority wetland systems, the expansive Northern and Central Highlands of Mexico's interior support approximately 11 percent of the country's wintering waterfowl. The lakes and reservoirs scattered through this vast region are visited by a variety of Central Flyway waterfowl, including Ross's, lesser snow, and greater white-fronted geese as well as pintails, green-winged teal, canvasbacks, and shovelers.

Many natural wetlands in Mexico's interior are threatened by declining water quality and excessive nutrient loads. For example, DUMAC is working with local communities to improve water quality in Lake Cuitzeo by improving nutrient management in the surrounding watershed. This project has received tremendous public support for improving the quality of life of local residents, while also enhancing wetland habitat for wintering waterfowl.

As you read this magazine on what is likely a cold winter day, many of this continent's ducks and geese are basking in the warm sun on mangrove wetlands and other important waterfowl wintering habitats in Mexico. While we may not be able to join them, we can take comfort in knowing that DUMAC is working to ensure that waterfowl will have the habitats they need to survive the winter and return north to their breeding grounds this spring to renew the annual cycle.

Eduardo Carrera is Ducks Unlimited de Mexico's national executive director and chief executive officer, based in Monterrey, Mexico, and Dr. Scott Yaich is chief scientist at DU national headquarters in Memphis.

Recognizing that many of North America's waterfowl winter beyond the borders of the United States, DU leaders formally incorporated Ducks Unlimited de Mexico (DUMAC) in 1974 to conserve the country's most important waterfowl wintering habitats. Forty-three years later, DUMAC has grown to become Mexico's recognized leader in wetlands conservation. Like its sister organizations in the United States and Canada, DUMAC's work is guided by sound science. For example, DUMAC is currently nearing the completion of a comprehensive inventory of Mexico's wetlands. This inventory will be used to guide important public policy and other habitat conservation efforts throughout the country.

Since its founding, DUMAC has conserved more than 1.9 million acres of wetlands and other wildlife habitat. Importantly, many of DUMAC's habitat conservation projects provide tangible benefits to local communities, including jobs, improved water quality, and training in conservation-friendly land management practices. In addition, DUMAC's internationally recognized professional capacity-building programs, such as RESERVA, extend the organization's conservation footprint to wetlands across Latin America and the Caribbean. Through these efforts, DUMAC has a remarkable impact on North America's wetlands and waterfowl.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy