Understanding Waterfowl: Return of the Trumpeters

Successful restoration efforts have helped these majestic birds make an impressive comeback

Successful restoration efforts have helped these majestic birds make an impressive comeback

By John M. Coluccy, PhD

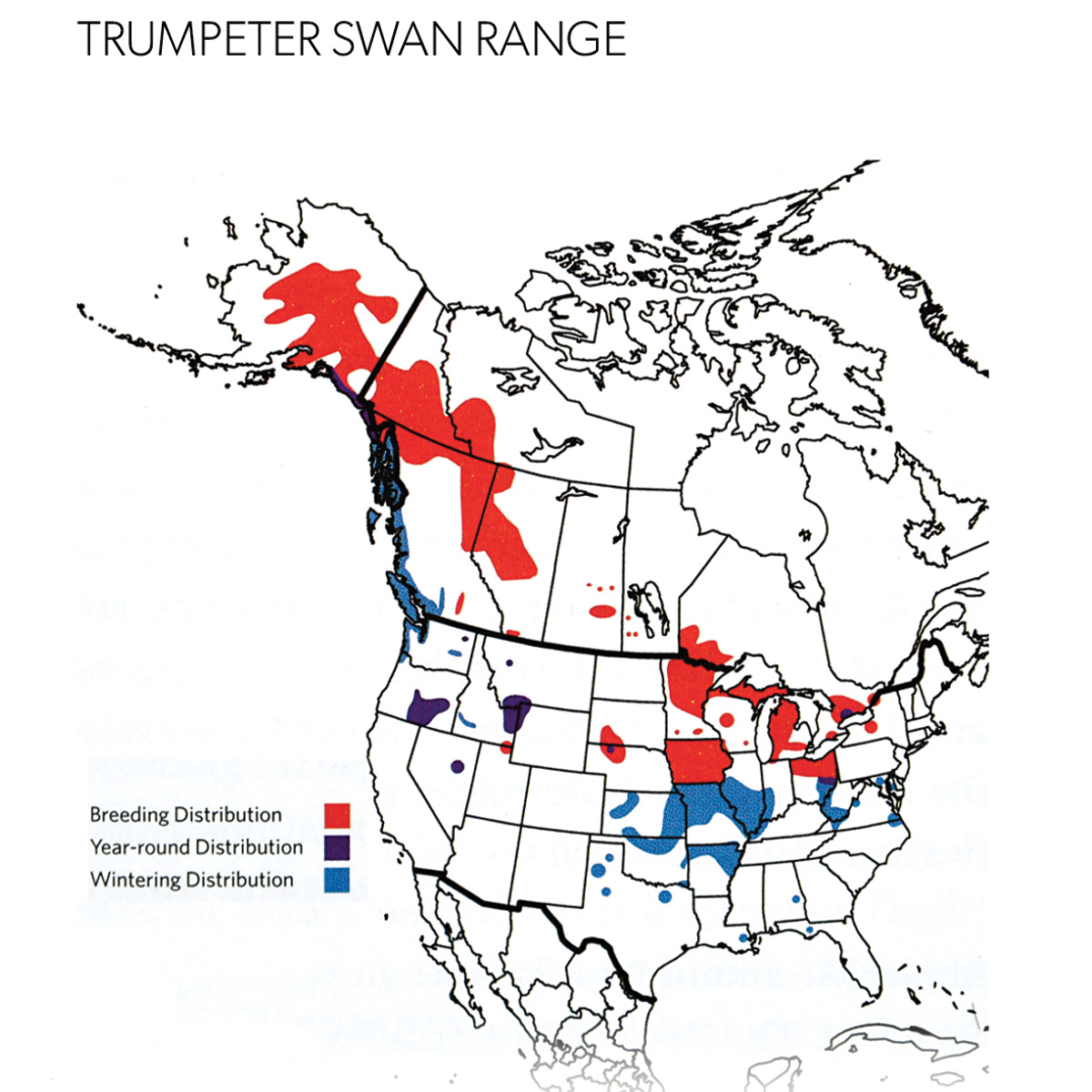

Trumpeter swans command respect. They are the world’s largest waterfowl, and their trumpeting calls announce their presence like royalty. Trumpeter swans were once widely distributed and fairly abundant across the United States and Canada. Their breeding range spanned from Alaska to western Quebec in the north and from the state of Washington to northern Indiana in the south. In winter, large numbers of trumpeters gathered in areas such as Chesapeake Bay, Currituck Sound, the lower Mississippi River Valley, the Gulf Coast, the Sacramento Valley, and the Pacific coast from Puget Sound to Alaska.

Sadly, by the early 1900s, decades of unregulated harvest had driven the trumpeter swan to the brink of extinction. Trumpeter swan feathers were used to adorn hats, their skins were used as powder puffs, and their primary flight feathers were coveted as writing quills. An estimated 108,000 swan skins were marketed by the Hudson’s Bay Company alone between 1823 and 1880. The quill trade was equally detrimental. Swan quills were preferred over goose quills because of their superior durability. Only the outer five primaries (wing feathers) were used, and the second and third primaries were considered to be the highest quality. Because left wing quills curved up and away from right-handed writers, they were the most desired. Noted artist, naturalist, and ornithologist John James Audubon preferred trumpeter swan quills for creating his artwork, saying they were “so hard, and yet so elastic, that the best steel pen of the present day might have blushed, if it could, to be compared with them.” In addition to the skin and quill trades, extensive trapping of muskrats and beavers during the same era may have also contributed to the trumpeter swan’s decline, as muskrat huts and beaver lodges are favored nesting sites.

The combined effects of this exploitation decimated trumpeter swan numbers. In 1932, a National Park Service survey found a mere 69 trumpeters in the entire contiguous United States at remote locations in and around Yellowstone National Park. About half these birds resided in the Centennial Valley of southwestern Montana, where hot springs and pools provided year-round open water. Across North America, it was believed that only 1,000 to 2,000 trumpeters remained, with the majority of the birds found in remote areas of Alaska. No more than 200 were left in all of Canada.

A century ago, trumpeter swan populations were near extinction. Thanks to a variety of restoration programs, their numbers have increased from about 3,700 birds in 1968 to more than 63,000 today.

The dire condition of the trumpeter swan population spurred a broad conservation movement that included federal protection of the species from harvest, conservation of key habitats, supplemental feeding, and ultimately reintroduction efforts in various parts of their former range. In 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act prohibited swan hunting in North America. To further protect remnant populations, the United States established Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge in Montana and Kenai National Moose Range in Alaska. These actions reduced illegal harvest and protected swans from human disturbance, especially during the breeding period. Supplemental winter-feeding programs were also undertaken at Red Rock Lakes to ensure swans survived the harsh winters. These early efforts resulted in a 10 percent annual increase in the Yellowstone population, which had grown to 642 birds by 1954.

Trumpeter swans and their eggs from the Red Rock Lakes area were used in early restoration programs at four western refuges in the late 1930s and 1940s and later at a refuge in South Dakota in the 1960s. In 1955, six trumpeters were relocated to the Delta Waterfowl Research Station in Manitoba. That transfer resulted in the first successful captive breeding of trumpeter swans and provided an additional source of birds for subsequent restoration efforts. In the 1960s, the Hennepin County Park Reserve District in Minnesota acquired 40 subadult swans from Red Rock Lakes to establish a breeding flock.

Early efforts to bring back the trumpeter swan were not entirely successful. Some birds were shot, others died from disease or injury, and a few were even stolen by collectors. In 1968, the Trumpeter Swan Society was founded to promote the restoration of the species across its historical range. The society provided much-needed expertise and a means for wildlife biologists throughout North America to share, compare, and improve restoration techniques. Restoration programs in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ontario followed in the 1980s and in Iowa and Ohio in the 1990s. Biologists from midwestern states often flew to Alaska to collect eggs for restoration programs. Zoos, private breeders, and a hefty amount of trial and error played a role in the success of these restoration efforts.

Today, federal management plans have been established for each of North America’s three major trumpeter swan populations: interior, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific coast. Several state-specific trumpeter swan recovery plans have also been implemented. To monitor the status of these populations, trumpeter swans are surveyed in late summer across their range in roughly five-year intervals. The first survey, in 1968, recorded only 3,700 birds. The most recent research (from 2015) estimates that the population had grown to 63,016 birds, compared to 46,335 birds in 2010.

Although the return of the trumpeter swan is a remarkable conservation success story and the population continues to increase, the species still faces an uncertain future. Lead poisoning remains a leading cause of mortality, as trumpeters often ingest residual lead shot and fishing sinkers while foraging for the roots and tubers of aquatic plants on the bottom of marshes and shallow lakes. Despite the bird’s protection from harvest, illegal shooting continues to pose a challenge and is more often associated with poaching than misidentification by sport hunters. Collisions with power lines also result in injury and mortality among trumpeter swans, but the installation of markers on power lines near important wetland areas can help limit these impacts. Finally, widespread wetland loss and degradation continues to threaten trumpeter swans as well as other waterfowl species. Through its on-the-ground wetland restoration and protection efforts, Ducks Unlimited is working diligently to ensure that trumpeter swans and other waterfowl continue to grace our skies for generations to come.

Trumpeter swans are long-lived birds; a wild female in Wisconsin lived to be more than 26 years old, and a captive bird lived to be 32. Like geese, trumpeters start forming pair bonds at two years of age and pair for life, but most don’t breed until they are four to seven years of age. These characteristics, along with a modest clutch size of four to six eggs, have resulted in relatively slow population growth for trumpeters compared to many other waterfowl species.

Tipping the scales at more than 25 pounds and boasting a wingspan of six feet, the trumpeter swan is nearly twice as large as its closest North American relative, the tundra swan. Getting airborne is quite an undertaking for these massive birds, as a football-field length of open water is required for them to paddle and flap their way into flight. Despite their immense size, they exhibit remarkable grace and elegance both on the water and aloft.

Dr. John Coluccy is director of conservation planning in DU’s Great Lakes/Atlantic Region.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy