Understanding Waterfowl: Redheads vs. Canvasbacks

These highly prized diving ducks are closely linked through unique interactions on the breeding grounds

These highly prized diving ducks are closely linked through unique interactions on the breeding grounds

By Michael G. Anderson, PhD

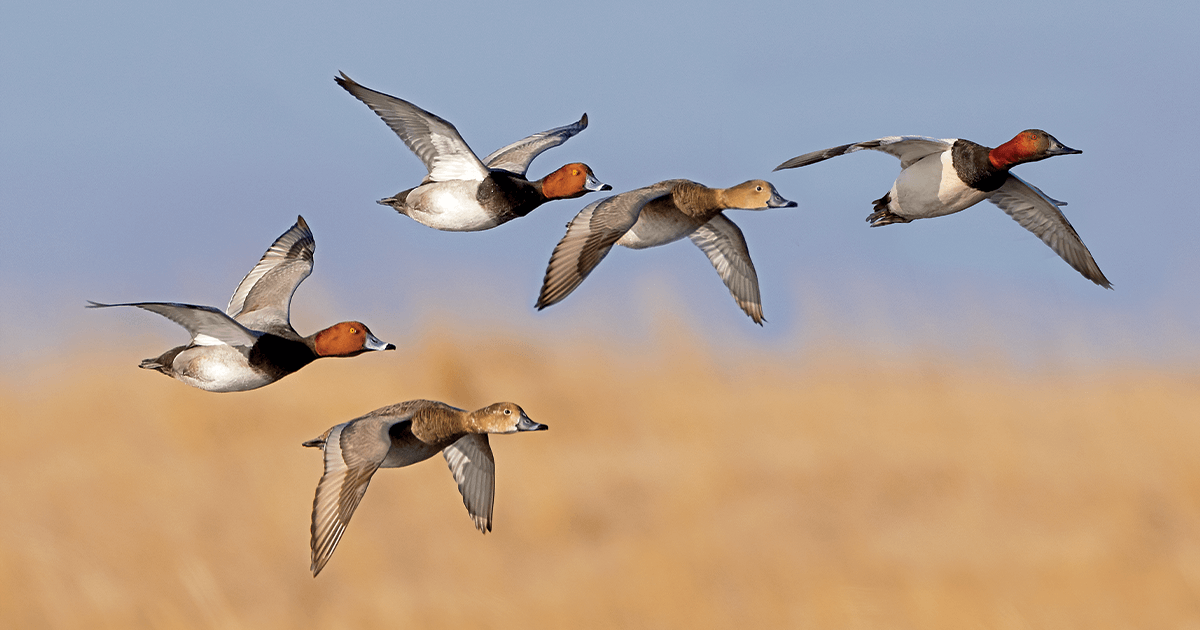

Anyone who watches ducks likely assumes that redheads and canvasbacks are closely related. Though similar in appearance, canvasback drakes have a whiter back and vermilion eye, while redheads have a gray back and yellow eye. The hens look even more alike. The female canvasback’s long, sloping black bill distinguishes her from the redhead hen, which has a grayer, curved, black-tipped bill. Both species are pochards, a group of diving ducks found all around the world.

What may be a surprise to many observers is that canvasbacks and redheads don’t appear to be each other’s closest relative. Dr. Michael Sorenson of Boston University, who studied breeding redheads in Manitoba, investigated the genetics of the pochard group. He found that canvasbacks are more closely related to European common pochards than to redheads, which are more closely related to ring-necked ducks. The ancestors of all these species likely arose in the Old World, with redheads and ring-necked ducks diverging from each other later, in North America, most likely with redheads in the west and ringnecks in the east. The ancestors of canvasbacks probably came over from Europe much later. Thus, genetic evidence suggests that the canvasback/common pochard group and the redhead/ring-necked duck group split apart a long time ago.

The present ranges of redheads and canvasbacks overlap, although in winter redheads are more likely to be found feasting on shoal grass in saline waters like the Laguna Madre, while canvasbacks prefer brackish waters with wild celery, arrowhead, and other tuber-producing plants. Breeding pairs of both species are common throughout the Prairie Pothole Region. Canvasbacks range farther north into Alaska, and redheads are more abundant in the Intermountain West.

Neither species is as numerous as many of North America’s dabbling duck species, perhaps because of the effects of varying water abundance on flooded nesting cover in breeding areas or the preference that redheads and canvasbacks have for special habitats and foods on migration and wintering areas. May breeding pair surveys show that average redhead abundance has increased from approximately 700,000 birds during the 1970s to around 1 million in 2022 and 2023. Estimated canvasback numbers were 587,000 and 619,000 birds during the last two years, respectively.

Both canvasbacks and redheads choose similar nesting habitat—usually thick, well-flooded stands of cattail, bulrush, and other emergent vegetation left from the previous growing season. Therein lies both a problem and an opportunity, depending on each species’ point of view. Decades ago, biologists discovered that redheads frequently lay eggs in canvasback nests. During the 1980s, Sorenson found that more than half of canvasback nests held parasitic eggs and around half of all redhead ducklings were reared by canvasback hens.

Since the 1950s, this behavior has received attention from other researchers, including Milton Weller, Rod Sayler, Dave Olson, and Mike Johnson. We’ve learned that the intensity of parasitic egg laying varies among years and places, that some redheads in some years only lay eggs in the nests of other ducks, some nest on their own, and some do both in the same season. Even a few canvasbacks lay eggs in other canvasbacks’ nests. Both local habitat conditions and the abundance of host nests seem to affect these choices.

Why is this a problem for canvasbacks? It comes down to two main issues: lost eggs and wasted time. Over-water nesters invest a lot of time in building their floating nests, so hens don’t just lay an egg in the morning and leave. Consequently, when a redhead comes around looking to lay an egg, the owner is likely to be home. Remote cameras reveal that tussles often occur, but even if they don’t, in the process of an intruder wedging in and laying an egg, some of the existing eggs can roll out of the nest. Fresh eggs sink and can’t be retrieved. Thus, by hatching time, the average canvasback hen’s clutch of nine eggs may contain only a handful of her own eggs, plus a number of redhead eggs.

Canvasback males offer a little help. Drakes waiting for their hens to rejoin them from nest building or egg laying usually wait on a pond other than the nesting pond, presumably to avoid attracting attention. But if the drake is present when a redhead pair or hen land on a nesting pond, he positions himself between his mate and the intruders, herding them away from the nest location. Once a canvasback nest has been discovered, however, the drake’s best efforts are seldom enough to dissuade a persistent redhead hen.

Curiously, after hatching, redhead ducklings seem to be welcome in canvasback broods. This hasn’t been extensively studied, but duckling survival in canvasback broods appears to be unaffected by the presence of the lighter-yellow redhead ducklings. Still, for the hen, rearing a brood takes time and entails risk—clearly a better proposition if most of the ducklings are her own.

Challenges don’t end at fledging. Newly hatched ducklings typically identify with and follow the first adult duck they see. For ducklings of most species, this is their biological mother. But that isn’t the case for redhead ducklings hatched by a canvasback. How do fostered redheads manage to choose the right species to pair with the following spring? In the 1970s, Mark Mattson, then a graduate student at the University of Manitoba, discovered that imprinting on sound is delayed in young redheads. However, more recent experiments by Sorenson found that fostered redhead drakes preferentially displayed to female canvasbacks the next spring. Nevertheless, canvasback/redhead hybrids are extremely rare. Something we don’t yet understand must be at play.

It’s interesting to ponder what kind of longer-term impact this parasitic behavior might have on these species. There is one place where breeding canvasbacks and redheads have been studied for more than 60 years—the Minnedosa pothole country in southwestern Manitoba. I arrived there in 1972 and have been observing the birds to some extent ever since. Mike Johnson, a current PhD candidate at Colorado State University, has shown that the probability of redhead parasitism is substantially higher now than it was when US Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Jerome Stoudt first monitored nests and eggs in the area. With a large sample of nests from 2015−20, Johnson found that about 82 percent of all canvasback nests had already been parasitized when they were first discovered by researchers, and nearly 90 percent had been parasitized by projected hatch dates. In contrast, Stoudt found that only 48 percent of presumptive first nests and 61 percent of late nests had been parasitized during his research in 1964−72. Other scientists in the 1970s and 1980s found intermediate results. The exact rates of parasitism are difficult to ascertain, as sunken eggs displaced from nests are difficult to find, but it seems likely that average rates of nest parasitism in the Minnedosa area have increased since the 1960s.

Over that same span of years, our indices of spring breeding populations of canvasbacks and redheads have shifted too, from canvasbacks outnumbering redheads by around two to one in the 1970s to redheads now usually outnumbering canvasbacks. But the trend isn’t clear-cut. Yearly fluctuations in pair numbers and the sequence of wet and dry years that affect both nesting strategies and redhead homing patterns all likely affect the degree of redhead parasitism of canvasback nests. It may take another generation or two of biologists to resolve the trajectory of this long evolutionary dance between these fascinating species—a dance that’s already well over 100,000 years long.

Dr. Mike Anderson is emeritus scientist with Ducks Unlimited Canada and a freelance writer based in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy