Understanding Waterfowl: Mild, Wet Weather Creates Tough Hunting Conditions

DU's chief scientist offers his thoughts on this year's frustrating season for many duck hunters

DU's chief scientist offers his thoughts on this year's frustrating season for many duck hunters

© Wayne Muzzy

By Tom Moorman, Ph.D.

Experienced duck hunters know that weather, especially harsh winter weather, is what drives flocks of waterfowl south in search of food and open water. This November, powerful cold fronts and snowstorms pushed ducks and geese from the northern reaches of the Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic Flyways, creating optimism among waterfowlers in central and southern states for the season ahead. However, nature occasionally throws a curveball to duck hunters, and that certainly has been the case for many of us this season.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) long-term forecast issued in October 2018 predicted a mild winter for much of the eastern half of North America. It appears that forecast has hit the mark. Open water and little snow cover are present across most of the United States. Wetlands and related food resources for waterfowl are available essentially from Nebraska east through Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, southern Michigan, Pennsylvania, southern New York, and Massachusetts. As of January 7, the snow and ice line was located at approximately 40 degrees north latitude. Such conditions make it a challenge to pinpoint waterfowl distribution, but it is reasonable to conclude that waterfowl are widely scattered across a very large area in the Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic Flyways.

During much of December, the south-central and southeastern United States have seen frequent low-pressure systems with abundant rainfall and associated river flooding. The wet pattern is in part due to the development of an El Niño event in the Pacific Ocean, which typically brings mild temperatures to the northern United States and Canada and cool, wet weather to the south-central and southeastern states. Many rivers from eastern Texas through the Carolinas are experiencing moderate to major flooding from repeated heavy rain events over the past four to six weeks, compliments of the ongoing El Niño.

What do waterfowl do when winter weather is mild and wet? Generally, mallards and some other species of waterfowl stay as far north as habitat conditions allow. This “strategy” theoretically enables the birds to minimize risk associated with migration and allows them to return to breeding areas as soon as possible in spring. For species like mallards and northern pintails, research suggests that females that return to the breeding grounds and establish nests earlier are more successful at hatching a clutch of eggs. Thus, the birds themselves appear to be “wired” to migrate only when necessary. This year, mild winter weather—and especially a lack of ice and snow cover—is enabling waterfowl to sit tight in more northern latitudes.

Even in areas where waterfowl are present, hunter success has been neither consistent nor high in many cases. This likely reflects mild temperatures that do not require birds to move much in search of food and may also reflect widespread habitat availability associated with frequent precipitation. This has led to some challenging and frustrating hunting conditions for many waterfowlers. In most southern and mid-latitude states, roughly three weeks remain in the duck season. It will take a significant change in this winter’s weather pattern, where Arctic cold plunges south and causes waterfowl to migrate in significant numbers, to improve many hunters’ fortunes. Regrettably, the long-term weather forecast appears to call for “more of the same” for much of the remainder of the month.

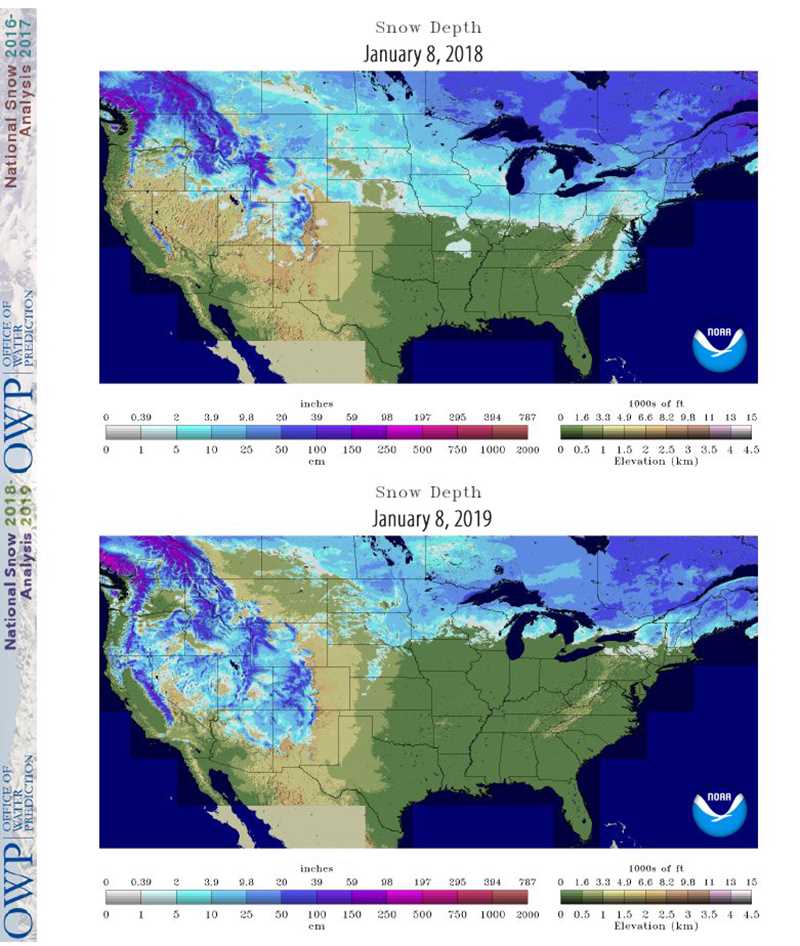

Waterfowl are highly mobile and well adapted to variable wetland conditions. The past two winters have given us remarkably different winter waterfowl distributions. The mild, wet winter we are currently experiencing is in stark contrast to the relatively severe winter of 2017−2018. This contrast in conditions reminds us that we must conserve key wetland habitats across a very large area of the continent to sustain waterfowl populations at healthy levels. From the prairies, which are traditionally considered the breeding grounds but also provide important stopover habitat for waterfowl in September and October, to the wetlands of the Gulf Coast and Mexico, Ducks Unlimited will continue to conserve crucial habitat to meet the requirements of these birds, regardless of where winter weather drives their migration.

Some useful and interesting links are provided below for those interested in trying to piece together the puzzle of this year’s waterfowl migration. Included are links to meteorological data, long-term weather forecasts, summaries of state waterfowl surveys, and other relevant migration information.

Snow and Ice Cover in the United States

Great Lakes Ice Cover

https://www.weather.gov/images/cle/ICE/dist9_combined.jpg

River Flooding Map

https://water.weather.gov/ahps/

Dr. Michael Schummer, SUNY-ESF Waterfowl Migration Predictor

Missouri Winter Waterfowl Survey

https://extra.mdc.mo.gov/cgi-bin/mdcdevpub/apps/wtr_survey/main.cgi

Mississippi Winter Waterfowl Survey

https://www.mdwfp.com/media/256240/dec-2018-aerial-survey-report.pdf

Louisiana Winter Waterfowl Survey

Arkansas Winter Waterfowl Survey

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1gWoS_rgv556QsC5kdcTU5wbHf7LmS0-R/view

October 2018 NOAA Long-Term Forecast

https://www.noaa.gov/media-release/winter-outlook-favors-warmer-temperatures-for-much-of-us

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy