Understanding Waterfowl: Avian Influenza Update

Here’s what waterfowlers should know about the disease and how they can help

Here’s what waterfowlers should know about the disease and how they can help

By Dr. Mike Brasher and Nathan Ratchford

Since it was first detected in 1996, the H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza virus has spread to wild and domestic birds around the world.

Duck hunters are eternal optimists. It’s what stirs us at 4 a.m., with coffee brewing and decoys rigged despite three straight days of empty straps. But occasionally, that optimism is challenged in unexpected ways. Such was the case during fall of 2022, when hunters reported alarming die-offs of snow and Ross’s geese in the Central and Mississippi Flyways, and western hunters witnessed Canada and cackling geese with cloudy eyes and zombie-like movements.

Testing confirmed H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) was responsible. Since then, HPAI has received extensive coverage in the media and has become a common topic of discussion among waterfowlers. In this article we examine the history of HPAI and share what we’ve learned about the disease at the center of this discussion.

Avian influenza (AI), also known as “bird flu,” is caused by naturally occurring viruses that primarily affect poultry and wild birds. These viruses can be categorized into many different subtypes, but all can be separated into two main groups—HPAI and Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI)—reflecting the degree to which they cause illness or mortality in domestic poultry. As the names suggest, LPAI causes little or no illness in domestic birds, while HPAI may result in 100 percent mortality in affected flocks. The effects of these viruses on wild birds, other wildlife, and humans, however, varies considerably. The majority of AI viruses in wild birds are of the LPAI variety, and outbreaks of HPAI historically occurred only in domestic poultry.

The H5N1 HPAI virus responsible for the current outbreak can be traced to 1996, when it was first detected in domestic geese in Guangdong, China. Scientists believe it originated from influenza viruses circulating among wild birds and domestic poultry in the region. H5N1 HPAI reappeared in Hong Kong in 2002, marking the first detection of the virus in wild birds.

Over the next 20 years, outbreaks of H5N1 HPAI occurred periodically in wild and domestic birds around the globe, each genetically linked to the 1996 Guangdong strain. This virus first appeared in North America in 2014, and by 2016 had resulted in the deaths of over 50 million poultry and $3 billion in damages. However, only limited illness occurred in wild waterfowl, and the outbreak eventually dissipated. Things changed in November 2021, when H5N1 HPAI reappeared in North America. By summer of 2022, infections among commercial poultry and wild birds were widespread across North America, and H5N1 had affected a greater number and diversity of birds and mammals in the United States than ever before.

Birds become infected with AI after drinking or feeding in areas containing virus left behind through feces or mucous shed by affected birds. Viruses are also spread through bird-to-bird contact. While waterfowl are a natural host of AI viruses and are involved in their dispersal, evidence of direct transmission pathways between wild birds and poultry is limited. Infection routes for domestic birds may more commonly include use of shared habitats and indirect contact from contaminated materials or surfaces. Human activities, contaminated equipment, and soiled clothing can also contribute to viral spread between poultry operations.

Symptoms of HPAI infections in birds include loss of coordination, swimming or walking in circles, inability to fly, a twisted neck, and death. However, not all infected wild waterfowl display symptoms.

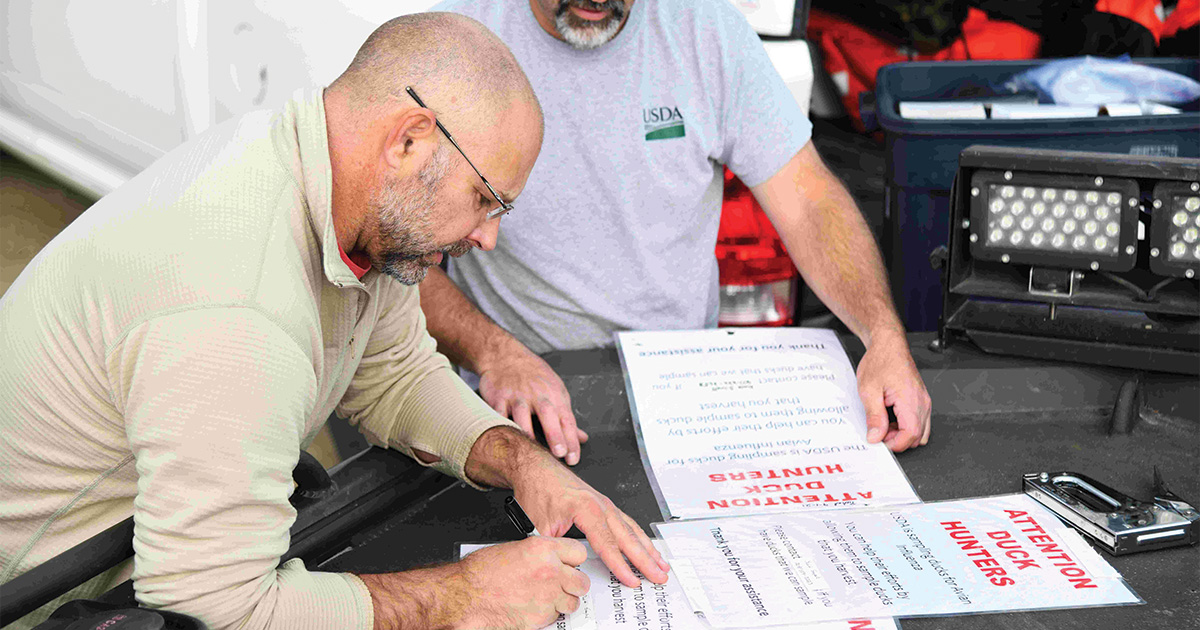

The US Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) plays a lead role in defending our nation’s food supply and agricultural community from HPAI through surveillance of both domestic and wild birds. Since 2022, APHIS has reported H5N1 in approximately 9,500 wild birds, although many more have likely been affected. The virus has been found in virtually all species of waterfowl, but illness and mortality have been particularly visible in snow, Ross’s, Canada, and cackling geese. First-year birds, which have not previously been exposed to the virus, may be most susceptible to infection, yet illness and death have also been reported in adult birds. Much remains to be learned about differences in disease susceptibility and severity across waterfowl species. Detections of HPAI in wild waterfowl have declined since 2022, although the virus continues to circulate. At present, biologists do not expect H5N1 to have significant long-term effects on waterfowl populations or directly affect harvest regulations.

Impacts of the HPAI outbreak have been most severe in domestic poultry. As of July 2024, an astounding 99 million domestic birds in commercial and backyard flocks across 48 states have been affected. The most significant recent development has been detection of H5N1 HPAI in dairy cattle, affecting 158 herds across 13 states. This was the first-ever detection of avian influenza in cattle, signaling the virus’s unprecedented ability to infect new hosts. The H5N1 HPAI virus has also been linked to illness or death in 20 other species of mammals, with transmission primarily resulting from scavenging of infected bird carcasses.

Although relatively rare, the H5N1 virus can infect humans. In the United States, four dairy workers with minor symptoms tested positive for H5N1 after direct exposure to infected dairy cows, and a small number of human infections were recently linked to contact with affected domestic poultry. Globally, H5N1 infections have sometimes led to serious human disease and even death, but health experts report that the overall risk to the general population remains low in the United States.

What should waterfowlers do to protect themselves and prevent the spread of HPAI? First, hunters should report sick birds or unusual deaths to state veterinary offices or APHIS. Second, hunters should follow all APHIS guidelines for handling harvested waterfowl. These practices are especially important for hunters who interact with commercial or backyard poultry flocks.

“You won’t always know if a bird is carrying the virus as not all infected waterfowl are symptomatic. If you are out in a wetland or field, assume one bird out there is carrying AI. Make sure to follow protocol and keep everything clean,” says Dr. Julianna Lenoch, National Wildlife Disease Program coordinator at APHIS.

Lastly, by participating in state and federal HPAI surveillance efforts, hunters can help scientists track changes in viral prevalence and genetic mutation. The long-term prognosis for H5N1 in North America remains uncertain, although most experts agree it is a disease we will contend with for the foreseeable future.

As for our canine hunting companions, a recent study found that transmission to domestic dogs is possible but very rare. Nevertheless, dogs should not be allowed to retrieve birds that appear sick or have been found dead. Hunters should also avoid feeding their dogs raw meat from harvested birds and prevent access to discarded carcasses.

It’s late summer now and we can feel the nights cooling and winds changing, bringing the promise of the waterfowl season to come. Optimism aside, we hope you’ll take the necessary precautions and share this information with your fellow hunters, because we all have a role to play.

For more information about Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, including FAQs and official guidelines and regulations for handling, cleaning, and importing harvested waterfowl, visit ducks.org/avianflu.

Dr. Mike Brasher is senior waterfowl scientist and Nathan Ratchford is conservation communications coordinator at DU national headquarters in Memphis, Tennessee.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy