Mallards in the New Millennium

An in-depth report on North America's most adaptable, abundant, and commonly harvested duck

An in-depth report on North America's most adaptable, abundant, and commonly harvested duck

By Drs. Mark Petrie, John M. Coluccy, and Mike Brasher

The Mallard is one of the most studied birds in the world. Since 1912, nearly 3,000 scientific articles have been devoted to Anas platyrhynchos. We know a great deal about these birds, from their favorite foods to their migration habits to the many factors that influence their breeding success. The challenge when writing about mallards isn't what to include-it's what to leave out! With that in mind, we decided to examine how mallard populations have fared in recent years and what this has meant to the nation's hunters.

The 1970s are rightly considered the modern gold standard for waterfowl populations. Duck numbers were high throughout much of the decade, even for species like the northern pintail. The national duck harvest soared as record numbers of waterfowl hunters took advantage of long seasons and abundant birds. Yet many hunters have little or no memory of the 1970s. For many contemporary waterfowlers, the late 1990s were the glory days. Twenty years ago duck hunters were enjoying a level of success that equaled or exceeded the 1970s.

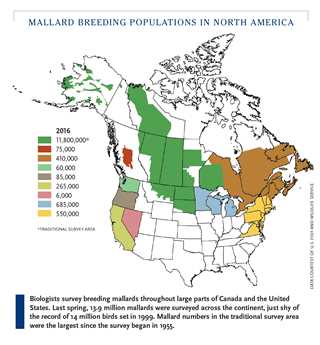

As the 1999 hunting season approached, Ducks Unlimited magazine provided a status report on our most abundant duck. That spring, biologists counted 10.8 million mallards in the traditional survey area (TSA). Although the Prairie Pothole Region is at the heart of the TSA, the survey extends as far north as Alaska. The 1999 count was the second largest on record, just missing the 1958 mark of 11.2 million birds. However, the TSA is not the only area where breeding mallards are surveyed. Several states and provinces outside the region also count mallards each year, and in 1999 these surveys tallied 3.2 million birds. All told, biologists counted 14 million mallards in 1999-a record that still stands today.

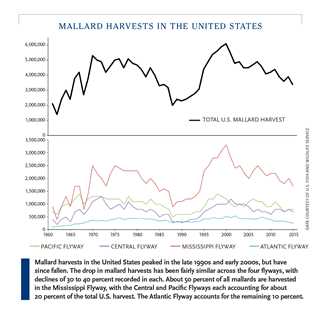

What about mallard harvests? In 1976, U.S. hunters bagged 5.1 million mallards, a record that stood for 20 years. This record was eventually broken during the 1990s, as growing mallard populations began to be reflected in the harvest. In 1997 the mallard harvest topped 5.4 million birds and then increased to 5.9 million by 1999. Amazingly, all this happened with fewer hunters in the field. In 1976 there were nearly 1.8 million waterfowl hunters; by 1999, that number had dropped to just over 1.3 million.

So what, if anything, has changed for mallards and duck hunters since the heyday of the late 1990s? To help answer that question we considered three things. First, how has the number of breeding mallards changed since 1999? Second, what is the link between mallard populations breeding throughout North America and hunters in each of the four flyways? And finally, how has the mallard harvest changed since the beginning of the 21st century?

Let's start with recent counts in the TSA. Although 1999 produced a near-record number of mallards, last spring was even better. Mallard numbers in the TSA have been on an incredible run since 2012, ranging from a low of just over 10 million to a record high of 11.8 million in 2016. Mallards in the TSA have obviously held their own since the late 1990s, but what about birds breeding outside this area? In 2016 the number of mallards surveyed outside the TSA was just over 2 million birds, down from 3.2 million in 1999. This hardly seems important given the TSA's high numbers, but it's a bit more complicated than that.

Until 2000, harvest regulations in all four flyways depended on the number of birds in the TSA. However, it was becoming clear that some groups of hunters were more reliant on other populations of mallards for their success. Dr. Todd Arnold of the University of Minnesota recently demonstrated this using a combination of mallard banding data and regional breeding population estimates. Over 95 percent of the mallards shot in the Mississippi and Central Flyways are produced in the TSA, mostly on the prairies and in the Western Boreal Forest. However, less than 15 percent of all mallards shot in the Atlantic Flyway originate in the TSA; the bulk of this flyway's mallards are raised in eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. Pacific Flyway hunters receive most of their mallards from areas west of the prairies, with Alaska and local production in states like Oregon and California supporting much of the harvest.

As the link between birds and hunters became clearer, waterfowl managers identified three separate "stocks" of breeding mallards. The midcontinent stock includes all mallards breeding in the TSA, minus Alaska mallards, plus those that breed in Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Hunting regulations in the Mississippi and Central Flyways depend on this stock. The eastern stock includes mallards breeding in southern Ontario and Quebec as well as in the northeastern United States. These birds determine seasons in the Atlantic Flyway. Finally, hunting regulations in the Pacific Flyway depend on the size of the western stock, which includes mallards breeding in Alaska, south-central British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California.

Although the size of the midcontinent mallard stock declined in the early 2000s, it has steadily increased over the past 10 years. However, mallard breeding populations in Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin, which are also part of this stock, have experienced a different trajectory. Breeding mallards in these Great Lakes states have declined from a high of 1.2 million birds in 2000 to fewer than 700,000 in 2016. Hunters in these three states rely heavily on local mallard production, so this decline is troubling despite the overall growth of the midcontinent stock. Half of all mallards shot in Minnesota are produced locally, and homegrown birds account for two-thirds of all mallards harvested in Michigan and Wisconsin.

Reasons for the decline in Great Lakes mallards are not fully understood. Duckling survival, nest success, and female survival outside the breeding season appear to have the greatest effect on population growth, but it's not clear if these factors have changed in recent years. The increase in Great Lakes mallards that occurred from the 1970s through the late 1990s coincided with a period of above-average precipitation. Drier conditions have prevailed in the region since 2000, and mallard declines have mirrored lower levels of precipitation, as have declines in blue-winged teal and wood ducks breeding in the Great Lakes states.

We know that most of the midcontinent stock has done well since the late 1990s, but what about their more coastal cousins? Most of the western mallard stock breeds in Alaska, where mallard numbers increased significantly from the late 1970s through the early 2000s before declining. In 1976, Alaska underwent a dramatic shift in climate that produced much warmer temperatures compared to the previous 25 years. This abrupt warming coincided with a shift in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), a long-lived El Niñominus;like pattern of climate variability. Cool PDO phases prevailed from 1890minus;1924 and from 1947minus;1975, while warm phases prevailed from 1925minus;1946 and from 1976 through at least the mid-2000s. Was the abrupt warming that began in 1976 responsible for the surge in mallard numbers? The greatest temperature increases occurred in spring, so it seems possible. Temperatures may now be cooling in Alaska, and it has been nearly 40 years since the last warming phase began. While it's too early to know for certain, the decline in mallard numbers could be related to a new cooler phase of the PDO.

The recent California drought also contributed to a decline in the western stock, where breeding mallard numbers fell from nearly 400,000 birds in 2012 to fewer than 200,000 by 2015. Water supplies for many wetlands were curtailed during the drought, significantly reducing the availability of breeding habitat for mallards and other waterfowl. Seventy percent of all mallards shot in California are produced within the state, and the decline in breeding birds hit California hunters particularly hard, as we'll see. Thankfully, California received plentiful precipitation last fall and winter, and most expect mallard numbers to rebound in the near future.

While important components of the western mallard stock have declined in recent years, the eastern stock has remained largely unchanged. Most eastern mallards breed in fairly stable environments where wetland numbers don't fluctuate much from one year to the next. Many of these same areas have an abundance of nesting cover, which probably contributes to the stability of these eastern populations. Interestingly, mallards were largely absent from eastern North America until the 1950s. Although the reasons behind their increase have been widely debated, it appears that the release of captive-raised mallards played a role. Researchers from Wright State University determined that eastern mallards are genetically different from their midcontinent and western cousins and are actually more closely related to Old World mallards-the ancestral stock of most captive birds. Since 1940, between 1 million and 2 million captive-raised mallards have been released in the Atlantic Flyway.

All told, biologists counted 13.9 million breeding mallards in 2016, barely missing the 1999 record of 14 million birds. But what has changed for mallard hunters? From 1999 to 2001, the U.S. mallard harvest averaged 5.8 million birds per year-the greatest three-year run since harvest statistics were first collected in 1961. Mallard harvests have since fallen nearly 40 percent nationwide, averaging 3.6 million birds during 2013minus;2015. This harvest decline occurred despite near-record numbers of mallards breeding throughout North America. During these same years, the total duck harvest also declined, but only by 20 percent compared to the 1999minus;2001 average. Although hunters were shooting fewer mallards, they were making up some of the difference by increasing their harvest of other species.

The drop in mallard harvest has been fairly uniform across the four flyways, with declines of 30 to 40 percent in each. Some of this may be due to hunter numbers, which fell from 1.3 million in 1999 to just under 1 million in 2015. However, other factors are undoubtedly at play, some of which differ among flyways and states. California hunters harvested 315,000 mallards per year during 1999minus;2001, only to see that average drop to fewer than 120,000 birds during 2013minus;2015. The record-breaking California drought, and its effects on local mallard production, is probably responsible for much of this decline. The story is similar in other states, such as Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin, where hunters rely heavily on homegrown birds. Total mallard harvest in these three states has fallen 30 percent, which parallels the decline in breeding mallard numbers within the Great Lakes states.

No discussion of the mallard harvest would be complete without some mention of the weather. Let's face it: mallards are hardy birds that often winter as far north as food and open water are available. The increasingly late onset of winter conditions throughout much of North America may be delaying the southern migration of mallards, a species already programmed to hang tough during inclement weather. It's hard to imagine that the recent decline in mallard harvest within the Central and Mississippi Flyways isn't somehow related to milder winters, given how well the midcontinent stock of mallards is currently faring.

It's probably worth remembering that the waterfowl world has a history of pleasant reversals when it comes to hunting success and that the mallard harvest remains well above the doldrums of the early 1960s and late 1980s to early 1990s. Still, Ducks Unlimited and its partners must continue to invest in habitat conservation programs that benefit breeding mallards in places like California and the Great Lakes states, given how important these regional populations are to local hunters. Although mallard numbers remain high on the prairies and in the Western Boreal Forest, much of this abundance is due to an extended wet period. While these welcome conditions will eventually end in drought, the incredible pressure on wetlands and grasslands on these landscapes will remain. Moreover, those other duck species that have helped offset the recent decline in mallard harvest are overwhelmingly produced in the same prairie and Boreal habitats. Hence, across the continent, DU and our conservation partners must continue to monitor landscapes, protect and restore habitat, and support public policies that sustain wetlands and waterfowl and the many benefits they provide to people.

Fifteen or 20 years from now, it will be a new generation of DU biologists who will provide an update in this magazine on the status of our most abundant, adaptable, and popular duck. Wherever you hunt, we hope the news is good. As in the past, that will be determined not only by the weather but also by how successful we are in our mission to conserve crucial habitats for mallards and other waterfowl.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy