Long Live the Canvasback

The future of this regal duck depends on conserving key wetland habitats, especially prairie potholes

The future of this regal duck depends on conserving key wetland habitats, especially prairie potholes

by Michael G. Anderson, Ph.D.

It was a tiny pothole, with a patch of cattails in the middle no bigger than a suburban living room, yet I knew she was there, sitting on a floating platform of broken cattails and new green shoots. We couldn't see her as we glassed the pond from the knoll to the northeast, so we moved quietly to the edge of the water. Finding just the right angle to peer into the cattails I spotted the hen-head down, neck outstretched, relying on stillness and her mottled feathers to hide her on the nest. We took a cautious step into the water but my companion caught his boot and splashed just a bit. Silently L-3, a four-year-old canvasback hen known by her green and white plastic bill marker, slid into the water, swam to a small opening in the cattails, and launched away into the wind with the patter of feet and an alarmed grrrack, grrrack, grrrack, grrrack!

I turned to my open-mouthed companion, a visitor from the Eastern Shore of Maryland, who was sputtering something about "Really? A pond this small? Why in the world? What is she doing here? I never would have believed..."

It was a familiar reaction of people who know canvasbacks largely from their big-water wintering grounds. In places like Chesapeake Bay, where "cans" are the stuff of legends, the birds congregate in big rafts on rolling waters like you see in a Ron Van Gilder painting, where getting close to the birds means lying low in big waves or patiently waiting in a wind-swept hide anchored near a shallow feeding area.

I explained that while not all canvasback hens choose ponds this small for nesting, it's not unusual. The late Jerry Stoudt of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) found 2,511 canvasback nests during 12 field seasons while wading around a southwestern Manitoba study area, mostly with his old Lab, Lisa Jane (who, like her master, harbored a serious hatred for raccoons). Stoudt, who logged more miles in hip boots than most of us rack up on Michelins, found that 65 percent of hen canvasbacks in his study area nested in ponds less than one acre in size despite having a wide array of wetlands from which to choose, and a remarkable 41 percent of canvasback nests were built in ponds less than a half-acre in size.

I studied canvasbacks for a while, too, in the same pothole country just south of Minnedosa (from 1975-1990) before I moved from Delta Waterfowl to Ducks Unlimited. In this area, breeding canvasbacks are as abundant as anywhere else in the world. In fact more than 10 percent of the world's population of these prized but uncommon ducks nest in the 10,000 square miles of knob-and-kettle terrain in southwestern Manitoba. If you drive by Minnedosa some day, look for the statue of the flying canvasback at the rest area at the junction of PTH 10 and HWY 16, erected by the town in recognition of the unique connection between this duck, waterfowl researchers, and this agricultural community.

Canvasback hens prefer to nest on heavily vegetated ponds with deep enough water to provide some protection from land-based carnivores like skunks and foxes. They also prefer to dine on the tubers of sago pondweed, a plant that requires permanent water to thrive. In this corner of Manitoba and parts of neighboring southeastern Saskatchewan there seems to be a magic combination of the right basin shape and depth, the right mix of permanent and more seasonal ponds, and the right water and soil chemistry to produce the nesting cover and foods the birds favor (sago and abundant aquatic insect larvae), and voil`-canvasbacks in good numbers.

Consistent with this reliance on dependable food and nesting conditions, in this region canvasback hens show extreme loyalty to previous breeding areas. The vast majority of canvasback hens return to the same home range they occupied in previous seasons. We know this from marking lots of birds with individually identifiable nasal "saddles," which allowed me to monitor the locations and behavior of one hen for as long as 12 years. That case was exceptional, but many hens having reached adulthood returned to the same breeding areas for several consecutive years. About 25 percent of marked female ducklings came back too, a proportion only slightly smaller than the number that we had estimated would survive their first year on the wing.

"One thing that remains constant between the wintering grounds and breeding grounds," I told my visitor, "is that canvasbacks rely on wetlands."

Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Unlike dabbling ducks that nest and sometimes feed in uplands (mallards, pintails, American wigeon, and other species at certain times and places), canvasbacks do everything on or under the water. Canvasbacks leave the water only to preen and oil their feathers, have a snooze, or maybe conserve body heat. And brood hens sometimes waddle as quickly as possible between potholes with a brood in tow. But canvasbacks and other diving ducks, with their feet placed well back on their bodies in order to paddle efficiently underwater, win no races on dry ground.

So put simply, conserving canvasbacks is all about conserving wetlands. "That may sound straightforward enough, but it's challenging," I said as my companion snapped yet another photo of the tiny nesting pond, an image that surely would be trotted out for display to unbelieving colleagues back home. The nest bowl held seven olive-buff canvasback eggs and a single parasitically laid cream-colored redhead egg, a common clutch for early incubation.

I explained that canvasback pairs occupy large and broadly overlapping home ranges-about one to 1.5 square miles here-and within that range use a dozen or more wetlands during the breeding season. Bigger ponds with good carbohydrate food supplies (especially sago tubers) are preferred by the birds when they arrive in spring, and the birds initially spend most of their time feeding, recovering from their long journey, and making ready to nest. As females begin to develop eggs they often seek out smaller seasonally flooded wetlands with abundant high-protein, calcium-rich invertebrates to nourish egg formation. They also begin to travel more widely, obviously exploring potential nesting ponds. "Many of these," I reminded him, "are smaller well-vegetated ponds like this."

If hens are lucky enough to hatch a clutch they lead their self-feeding ducklings to ponds with appropriate food for their developmental stage. Typically broods move to successively larger and more permanent ponds over the nine weeks or so that hens look after their ducklings. Such moves occur as the ducklings' high-protein diet begins to include some plant matter and smaller wetlands recede as summer wears on.

This pattern of movement means that canvasbacks use a wide array of wetlands between their spring arrival and autumn departure. Just conserving the big ones (where many of us tend to see ducks when we are afield in the fall) won't cut it. Nor will "consolidating" small ponds into larger ones as the agricultural industry would like to do. And protecting them all is difficult because the smaller ones in particular are a nuisance to grain farmers, who have to operate around them with bigger agricultural implements than their grandfathers ever imagined. Some combination of incentives and regulations will likely be necessary to ensure canvasbacks have the wetland habitat required to sustain their current numbers.

By mid- to late June, with successful hens incubating eggs and the calendar ticking down to the time when renesting is no longer feasible, canvasback hens without broods and drakes gather in flocks on larger food-rich ponds and then gradually trickle away from the pothole country. Most head north to larger lake-marsh complexes in the southern boreal forest where permanent water and reliable food supplies can sustain them during the coming month or so when they will molt their wing feathers and cannot fly. Here, once again, in the journey through their annual cycle, canvasbacks become birds of the big water.

By September as the aspens start to glow and the morning wind begins to bite, both molting adults and maturing young are on the wing. Little by little the birds gravitate toward staging areas where food is abundant. These, by no coincidence, are places of waterfowling legend: Beaverhill Lake, Alberta; Lake Winnipegosis and Delta Marsh, Manitoba; Lake Christina, Minnesota; Lake Onalaska and Stoddard Pool, Wisconsin; Lake St. Clair and Long Point, Ontario; Keokuk Pool, Iowa; and many more.

On these marshes, as well as on the big waters of their wintering grounds, conservation of canvasbacks must be about sustaining or improving the health of whole watersheds. With changing water quality, canvasbacks have adapted their diet to clams and other invertebrates in many places, but historically, migrating and wintering canvasbacks relied on sago pondweed, wild celery, arrowhead (duck potato), and other tuber-forming plants. The common prerequisite for growing these plants is clear, productive water. Sedimentation, eutrophication, common carp, and pollution can all greatly limit the abundance of these plants and their capacity to support hungry ducks. Securing and maintaining the quality of North America's lakes and rivers is an enormous challenge, and the outcome will materially affect the future of canvasbacks as well as people.

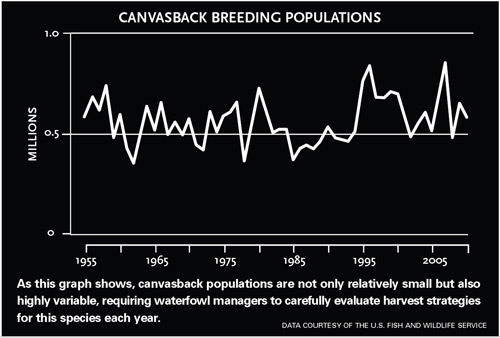

A scarcity of good breeding and wintering sites for canvasbacks may contribute to the relatively low numbers of these birds that have been tallied since the 1950s. In 2010 the canvasback breeding population was estimated by the USFWS and Canadian Wildlife Service to be 585,000 birds, down some (12 percent) from 2009 but still slightly above the 1955-2010 average of 570,000 birds. Both of those apparent differences, however, are within statistical sampling error.

Because canvasbacks are less abundant than many other ducks and unevenly distributed across a vast geographic area, estimates of annual breeding population size tend to be relatively imprecise. Looking over the long term, the pattern of year-to-year population changes in canvasbacks (see graph) appears to be more erratic than in mallards, which have had rather well-defined periods of scarcity in the 1960s and 1980s with offsetting peaks in the 1950s, 1970s, and 1990s. Of course mallards are much more abundant and widely distributed throughout the surveyed area than canvasbacks.

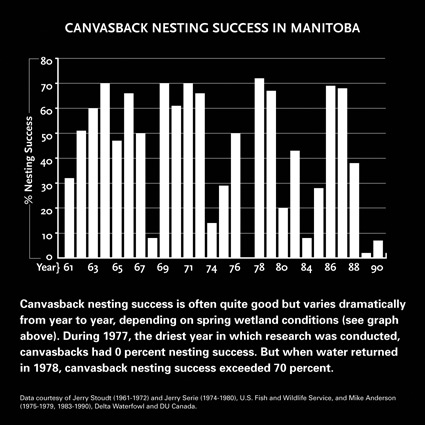

Surveying issues aside, canvasback numbers may indeed vary widely from year to year as dramatic annual changes in water levels and nesting success have been observed on their prairie breeding grounds. For example, data combined from three different studies conducted over a 30-year span in southwestern Manitoba found that canvasback nesting success in this region changed abruptly from 0 percent in 1977 (a dry year) to 70 percent in 1978 (a wet year). Several other years show changes of similar magnitude (see graph). I suspect that episodic drought like this may impose substantial limits on canvasback population growth.

Fortunately for canvasbacks, the widespread degradation of upland-nesting cover, largely as a result of agricultural intensification, has not been a factor. So we haven't seen a declining trend in canvasback nesting success as has been observed for some upland-nesting dabbling ducks. What is clear, however, is that conserving the array of prairie wetland basins on which breeding canvasbacks depend will be vital to sustaining their populations.

Speculate as we may about canvasback numbers in the distant past, 55 years of data are enough to convince me that a rational goal for waterfowl managers would be to hang on to the canvasbacks we currently have-a modest but still huntable population of this extraordinary game bird. North America appears capable of supporting an average population of about 500,000 to 600,000 canvasbacks as long as we do not suffer significant losses of the remaining wetlands vital to the birds.

With conservative regulations in place to help ensure a sustainable harvest, fewer people hunt "King Can" than once did. But because of their restricted distribution and the challenge of hunting their wide-open haunts, cans were never everyman's duck like mallards are. Yet everyone should witness once in their lifetime the thrill of a flock of cans ripping over decoys on a crossing wind. The startling roar of wind through a hundred locked wings. The surprising snap of feathers straining against the air and the momentum of a duck trying to change direction fast. Dazzling white birds against indigo water in the evening light.

These ducks and their pursuit embody all that is great in our hunting heritage: the beauty of wildfowl on the wing; the thrill of "bringing 'em close;" traditions of canoes and duck boats, handmade blocks, and old friends; the irresistible pull but tinge of danger that comes with hunting big water; celebration of table fare without equal; and the commitment to conserve and sustain a precious resource.

May we always have the opportunity to meet these legendary birds up close and personal! This shall be so only if we look after the wetlands that sustain canvasbacks across our continent. Like a flight of cans arrowing through an autumn sky, our course is clear. Let us not fail the birds, or future generations, in our resolve.

For more information on DU's efforts to conserve key habitat for canvasbacks and other waterfowl, go to www.ducks.org and www.ducks.ca.

Dr. Mike Anderson is senior conservation advisor at DU Canada national headquarters at Oak Hammock Marsh.